You do a lovely underpainting and you lose it in the top layers. Why does that happen?

|

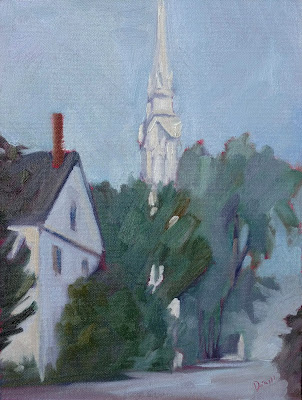

| Fog Bank, by Carol L. Douglas. This will be on display at Maine Farmland Trust Gallery later this month. |

The human mind loves complex, irrational space divisions. The same mind perversely regularizes what it paints and draws. A split-rail fence, where the gaps between posts diminish haphazardly into infinity, attracts us when we see it. However, unless we’re mindful, when we paint it, we regularize the spacing. The same thing happens with trees, flowers and clouds. In nature, they’re artfully erratic. We too often space them in neat lines. Bobbi Heath calls this anti-entropy. It’s a good description of the brain’s powerful impulse to push ideas, images and tones into patterns.

We’re best at drawing when we’re fresh. The challenge is to keep that freshness throughout the finished layers of a painting.

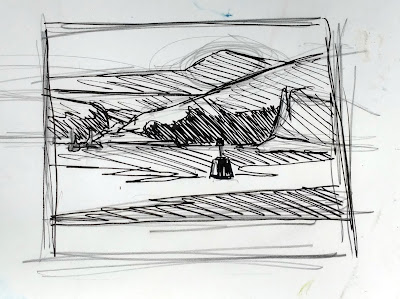

|

| Visan Vineyard underpainting, by Bobbi Heath. |

Bobbi graciously allowed me to share an example for this post. She painted the underpainting above last year in France and finished the work this month in her own studio. That in itself is a challenge. No matter how good your visual memory is, it diminishes over time. You’ll always be most accurate if you finish work quickly.

Bobbi made significant changes between the drawing and the final work. The far hill doesn’t rear up as energetically. The ends of the rows are lower on the canvas, and thus less important. More critically, she reduced the contrast, softened the perspective lines, and the ends are less incisive. She also changed the value of the midfield. In my opinion, the painting was weakened by these changes (although it’s still beautiful).

|

| Visan Vineyard, by Bobbi Heath. |

I stress drawing on paper before painting, instead of going straight to the canvas. It’s important to work out the compositional questions before you pick up a brush. It’s just as important to have reference to consult when the light changes or your painting gets distorted. A photo on your phone will just tell you what was there, not how you drew it.

Avoid too much solvent in the bottom layers. In alla prima painting, the bottom layer should have enough OMS in it to move fluidly, but not enough to run. You cannot keep a tight drawing if you’re painting over mush, nor can you keep the colors separated and bright. If you have laid down too much pigment (and it should be thin) lighten it up with a rag, not an OMS-soaked brush. If you can see reflections in your underpainting, it’s too goopy for clean alla prima painting.

It’s a fallacy to think that you draw first and paint second. Painting is continuous drawing, and the initial drawing must be restated constantly. I leave important lines showing until I’m certain I have finished the passage, and sometimes I don’t obliterate them at all. You can’t cover up your drawing and expect to reiterate the freshness of the original line. That early drawing will always be your most delightful.

|

| Home Farm, by Carol L. Douglas. This will be on display at Maine Farmland Trust Gallery later this month. |

I prefer to work large in general. It’s easier to be accurate and poetic with a large sweeping line. The smaller the canvas, the more jarring small errors of measurement become. For most brushwork, I recommend holding the brush at a point more than halfway back from the ferrule. That gives your brushwork bounce and grace. But for accurate fine drawing, hold it like a pencil.

Kudos to Bobbi for offering to let me critique her painting publicly. “I wish I’d showed it to you earlier so you could have told me to restate the drawing,” she said. That’s a pal.

A version of this post first appeared in October, 2019.

.jpg)