Over time, the dark passages in an oil painting can grow hazy. In watercolors, the beautiful, jewel tone on the palette can look flat and dull after the paper dries. That’s ‘sinking’ color, and an ounce of prevention beats a pound of cure.

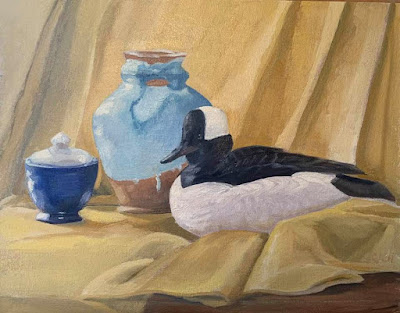

|

| Clear Morning on Bunker Hill, 24X36, $3985 framed. |

Oil painting: Sinking is caused by the displacement of the oil in the top layer. It’s most obvious in dark passages, but that’s only because the dusty haze is most visible there. It appears slowly over time—a painting that was once exuberantly colorful is suddenly dull. The different drying times of pigments means that color will sink unevenly across the canvas, giving it an irregular, blotchy look. Details that were once subtly beautiful will disappear.

Sinking can be repaired by oiling out or varnishing, but this may need to be repeated to keep the painting beautiful. If a painting is sold, you have no idea if it’s losing its color. It’s far better to do it right in the first place.

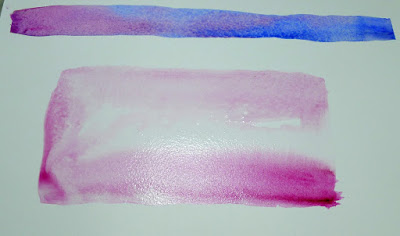

|

| Tom Sawyer’s Fence, 14X18, $1275 unframed. |

Sinking has three common causes:

Too much solvent—the painter has not mastered the art of using unadulterated paint or painting mediums in the top layer. He relies too much on odorless mineral spirit (OMS) to get good flow. The OMS takes the place of the linseed oil binder and then evaporates. That leaves the pigment particles isolated, with no oil surround. Air doesn’t have the same refractive index as linseed oil, so a pigment that looks dark and beautiful in solution looks dull and grey when the binder disappears.

Not enough oil in the top layer of paint—this is why we keep repeating that old saw, ‘fat over lean.’ There’s enough oil in modern paints to make a solid top layer, but only if applied in proper thickness. If you want to paint thin, you must cut your paint not with OMS but with an oil-based medium.

Over-absorbent grounds—acrylic gesso is more absorbent than oil gesso, but a well-prepared acrylic ground is fine. However, a very inexpensive board may not have enough ground to stop oil from seeping through. An aftermarket coating of gesso is a good cure. Non-traditional grounds like paper and raw fabric need very careful preparation.

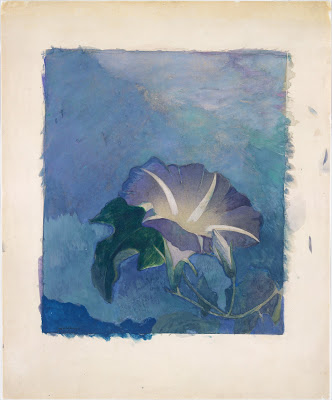

|

| Bunker Hill overlook, full sheet watercolor, available. One of the advantages of Yupo is that there is no sinking. |

Watercolor: “The difficulty in watercolors is not that it is ‘unforgiving’, as amateurs widely misbelieve: it is that it begs for fussing,” wroteBruce MacEvoy. That fussing takes the form of overworking passages. Alla prima, or ‘on the first strike’ is vital in watercolor.

We want the pigments to stay on the top of the paper, rather than sink into it where they can’t be seen. The cellulose fibers of watercolor paper were laid down in a stiff mat so that pigments will sit nicely on top. Reworking wet-on-wet, scrubbing, and other repairs cause the fibers to unravel, creating a microscopic forest of random threads. Paint sinks into its crevices. The color is duller and, worse, blotchy.

|

| The deck of American Eagle, from my sketchbook from Age of Sail workshop. |

Most watercolor paper is coated with gelatin or other sizing. This controls its absorption of paint. When you do a preliminary wash of color, you’re wetting the paper along with establishing primary shapes. If this wash layer is allowed to dry completely before the next layer is applied, the water and paint mix with the sizing and create a new layer, comprised of binder, sizing and pigment. That new, dense sizing layer can help hold successive layers of paint on the surface.

But if you ‘lick’ the wet paper constantly with your brush in an attempt to control minor flaws, you interrupt this process. Unless the paper dries completely between approaches, each pass with the brush lifts more paper fibers. That disturbance increases the capillary action that draws the pigment deeper into the paper. Overworked passages look dull and fuzzy.

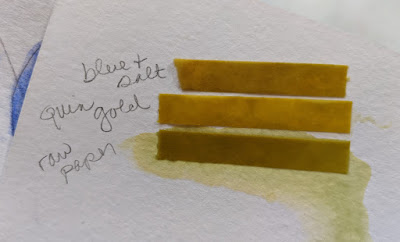

Of course, the type and quality of the paper you use matters. Hot press paper is more tightly-compacted, making it more tolerant of overbrushing. Cold-press paper has less sizing and looser fibers. It tolerates less fussing.