Water is infinitely variable, and that means there’s no one way to paint it.

| Electric Glide, by Carol L. Douglas. The length of reflections may vary, but they do need to be directly below what’s being reflected. |

Artists often trip up where things have a general pattern but can’t be predicted precisely. We either ignore the pattern altogether or overstate it into rigid regularity. These stochastic processes are everywhere in nature, but most especially in the behavior of water.

Water can be utterly still, random and choppy, or it can create orderly patterns of ripples or waves. When it hits an obstacle like a ledge or the shore, its surface is distorted by what’s happening underneath. In a rainstorm, fresh water floats on the surface of salt water, adding another pattern.

|

| Ripple pattern off the deck of American Eagle in Stonington Harbor, by Carol L. Douglas |

With all that variety, there’s no one way to paint water. In my Age of Sailworkshops, we paint repeated quick studies of waves and light; none of them are ever the same.

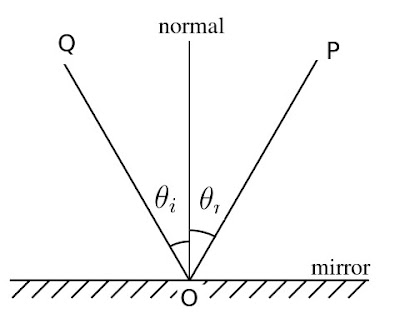

Reflection involves two rays – an incoming (incident) ray and an outgoing (reflected) ray. Physics tells us that the angles are equal but on opposite sides of a tangent. This is immutable. It’s why reflections of a boat, lighthouse or tree must run down in a straight line to the viewer’s feet.

|

| Parker Dinghy, by Carol L. Douglas. You can see into water when you’re looking straight down into it, or into the side of a wave. |

The surface of water is not perfectly reflective, although it can come very close. Some rays of light are absorbed rather than bouncing back at us. This happens in both directions, so we can see some of the color (or objects) under the water.

| Waiting to play, by Carol L. Douglas. The bands of orange are reflected light from underwater. Available from the artist. |

Moreover, water is never absolutely flat. Even the slightest breeze distorts its surface. Although waves start out as regular oscillations, they are rapidly distorted by wind and current. Their surface can be rough and infinitely varied. Light rays are reflected at many different angles, radically disrupting the image. This can give the surface of the sea or its spray a solid or matte appearance.

Where we look directly into water, it’s the least reflective. That can either mean looking straight down or into the face of the wave (where it appears to be green). The tops of the waves reflect the sky, but the sky isn’t the same color in all directions. Other surfaces reflect what’s in the distance—moonlight, other boats, structures, trees.

|

| Three Graces, by Carol L. Douglas. The closer the object, the longer its reflection. |

While a reflection must be lined up horizontally with what’s being reflected, that doesn’t mean the reflection will be absolutely symmetrical if you turn the canvas on its side. Tall objects are (generally) taller, but the farther away they are, the shorter they appear in a reflection. So, a mountain may loom in the scene in front of you and be relatively shorter in the reflection.

In still water, ripples are generally elliptical, although they may join in long strings or twitch with the vibration of the breeze. As water becomes less still, it generally sorts itself into waves.

|

| Breaking Storm, by Carol L. Douglas. Waves start as regular oscillations and are distorted by wind and current. Available through Folly Cove Fine Art, Rockport, Mass. |

Most of us see waves when they’re approaching the shore. There their behavior changes radically. They tend to pile up as the water gets shallower, effectively growing taller and slowing down. As they break, all predictability ends. The spray from a breaking wave can and does go anywhere.

If you live where it’s still warm enough to paint outdoors, find a body of water near you, and draw or paint the reflections. My Zoom classes are going at this a little differently; we’re going to paint the reflections in a pie-plate of water or in a mirror. It’s not the setting that’s important; it’s the reflections that we must master.

New Zoom classes start December 7-8; current students have priority, but if you want to be added to the list, email me. And it’s that time of year when you can get Early Bird registration discounts for my workshops—for Age of Sail, Pecos, and Sea & Sky.

This weekend I got one of the best endorsements imaginable, from student Beth Carr. “I kept saying ‘in my retirement’ but one never knows. I figured I’d better not wait! Carol’s Zoom class is helping save this pandemic period from being a total bust. And I’m SO glad I came to Schoodic and met you all.”