Autumn, I like to tell visitors, is the most beautiful season in New England. This year is determined to make a liar out of me. It was wet and cold during my watercolor sailing workshop. Here at Cape Ann Plein Air (CAPA) neither the wind nor sky have cooperated.

Natalia Andreeva saw me shivering in my fleece, thermal vest and flannel shirt. She added her windbreaker, tying the hood tightly over my head. “Keep it for the week,” she said. I’ve taken her up on the offer so seriously I’m almost sleeping in it. It’s sad when a woman from Tallahassee has to dress a woman from Maine for cold weather.

Although these events are competitions, painters are overwhelmingly kind to one another. Stewart White learned the hard way that his rental car has a bum charging system. Kirk Larsen had jumper cables and fired the thing back up in a field at Allyn Cox Reservation. I saw Stewart yesterday at the Essex Shipbuilding Museum with a small portable charger in his hand. “I’ve learned how to open the hood,” he said cheerfully.

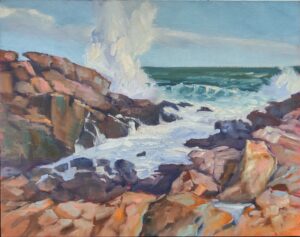

The howling winds have resulted in spectacular rollers and breakers. My Maine town is protected from raging seas by Penobscot Bay, so these waves are a real treat. However, the wind is an ergonomic problem, as it makes the canvas vibrate, when it isn’t just flipping away in the wind. Yesterday, Eric Jacobsen, Mitch Baird and I found a deep cleft in Bass Rocks in which to set up like three little monkeys in a row. That meant we were all painting the same view.

That really didn’t matter, as we’re very different painters. I find this distracting at times, as I really would rather paint like Mitch or Eric or my buddy Ken DeWaard. I’m always tempted to copy off their papers.

Even when we start with the same fundamental composition, we put the marks down in our own individual ways. That scribing is the actual meat of the painting; the rocks and crashing seas are just the subject. I’ve found that painters are often uncomfortable with their own handwriting. Done right, it says something deeply personal about us.

The great conundrum of painting is that it’s supposed to be revelatory, but we creators frequently don’t like what we see in our own work. A psychoanalyst could have a field day with that.

“The essential thing,” Henri Matisse wrote, “is to put oneself in a frame of mind which is close to that of prayer.” Apparently, Matisse’s friends were quieter than mine. I’m a mutterer; Eric is a fixer; Mitch is more of a self-flagellator.

The good thing about painting in these conditions is that you can’t overthink what you’re doing. You just do it, wipe the salt spray off your face, and do it again. Sooner or later, something is bound to work.

“A picture must possess a real power to generate light and for a long time now I’ve been conscious of expressing myself through light or rather in light,” Matisse also wrote. In the following century, that became the major mantra of painters: we’re not painting objects, we’re painting light.

That’s great as long as the light cooperates, but this week has been one of morose and glowering skies. We’re all struggling against it. But cranky seas and skies are very much a part of the maritime tradition of Gloucester and Maine, as evidenced by so many of Winslow Homer’s paintings.

It’s raining now, and I’ll take the morning to frame and enter my paintings onto CAPA’s online system. Rae O’Shea just stopped by on her way out to take photos. “They’re talking frigid temperatures on the weekend, and possible flurries,” she said.

Why didn’t I bring my winter jacket?