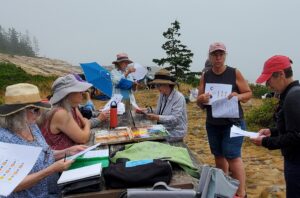

I’m in Acadia teaching my annual Sea & Sky workshop, and yesterday was a fog-bound day. We were at Blueberry Hill. The great granite slope, the spruces, and Schoodic Island drifted in and out of their wrap of soft wool. Not only do I love painting in this atmosphere, but it is a wonderful sensory experience. Fog can be grey or greenish or blue or even pink. It’s cool on the skin, sound is deadened and distorted, and one feels a sense of peace and solitude (assuming one isn’t attempting to navigate a tricky channel without satnav or radar).

“There is no extra charge for the facial,” I told my students.

At around 11, the fog started to burn off. The sea glowed blue against the pink rocks. Offshore, every spruce on the island was picked out in relief. A regular observer of the coast would have bet that it was clearing for the day—and would have lost the bet. In as much time as it would take to redraft a painting to reflect these new optics, the fog settled back in.

It was ebb tide when we arrived. Blueberry Hill has wonderful irregular tidal pools rimmed with seaweed. Long fingers of granite reach down into the sea, and a spit of surf-worn cobbles stretches out into East Pond Cove. They’re a design delight, but you have to work fast. By the time we finished for the day, the sea had come in, covered every rock, and was receding again.

“Why does anyone paint plein air?” asked a student in exasperation. “It’s always changing!”

That is, of course, the point. There is dynamism in these changes, whereas reference photos are never more than a vague approximation of what happens in nature. Yes, I sometimes paint from photos—we all do—but it’s never as informative or energizing as painting outdoors.

I see Dennis during my Sea & Sky workshop. He’s accompanied his wife Paula for the past few years. While we’re painting, Dennis goes birding and hiking. “I saw a family of sharp-shinned hawks,” he told me yesterday. I was curious about how he identified them, and he told me about the app Merlin Bird ID. Last night I put it on my phone.

When you spend a lot of time standing in one spot outdoors, you hear lots of birds, and you meet a lot of birders. Hikers, bicyclists and kayakers amble through your field of vision. Our disciplines are united by a common reverence for nature, so we always have something to talk about.

Radical changes in weather can be disconcerting. I won’t paint outdoors in a snowstorm or an electrical storm, for example. Extreme heat can be just as dangerous, but luckily, it’s not part of my everyday experience.

Last night, we met to paint a nocturne. On the way over, Cassie saw a black bear cub. That’s an experience you’d never have in your studio.

We set up at 8 PM outside Rockefeller Hall. It’s elegant and old, and we could turn on interior lights. We distributed headlamps and easel lights. I settled down in a corner, excited to spend time with my watercolors after a day teaching. Nocturnes in watercolor are challenging in their own right, and even more so in the damp of a foggy night. It can be like painting into a wet paper towel.

Forty-five minutes later, the skies dumped on us. Our gear, our paintings, and our composure were all soaked to the bone. We scrambled to pack up, laughing and chattering in the cold rain. Yes, we could have been in our rooms painting from photos, but instead we had a convivial adventure, and a new story to tell.