I used to do an annual invitational plein air event in lovely Rye, NY. It’s just above New York City and home to an historic amusement park. That means lots of day tourism.

Rye has a beautiful shoreline, but waterfront streets are all marked with no-parking signs. Although the sea is a resource that nobody-and-everybody owns, access to it is restricted to a few lucky people.

Rye is ranked the 30th wealthiest town in America. Over two decades I’ve gotten to know enough people there to see beyond that. However, those parking signs, as necessary as they are, contribute to an us-vs.-them rift in the eyes of the casual visitor.

The problem isn’t limited to New York, as a recent letter to the Portland Press-Herald points out. Residents of Cape Elizabeth are concerned about parking near a Cape Elizabeth Land Trust (CELT) property called Trundy Point. The town is considering restricting parking there, as they have at Cliff House Beach.

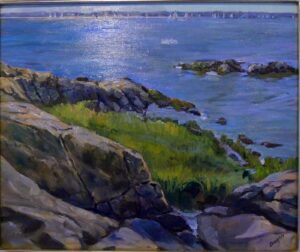

Trundy Point is a small, rocky promontory jutting out into the ocean, with an equally-small beach to one side. It’s not overrun with visitors; in fact, I needed help finding it. I spent two days last year painting it for CELT’s annual Paint for Preservation. (CELT plays no part in this potential restriction; it would run counter to their mission.)

But Trundy Point is nestled among very nice homes, homes which Average Joe might identify as belonging to the uber-rich. Restricting parking plays into that stark question about who owns access to the ocean.

(Of course, the flip side of cars at Trundy Point is that CELT has ensured that spit of land will never be built on. That preserves the oceanfront view for its neighbors, increasing their property values.)

I had the good fortune to spend a month in Australia. There, all beaches are Crown land, meaning they’re for public use. Any land below the high-water mark belongs to the public. Like here, each state has its own rules, but where my cousins live in Victoria, permanent building is restricted to the far side of the road. The only thing that’s on the beach side are those curious, lovely structures the Brits call beach huts.

It's too late for us to go back and change the rules here. That means that the only public coastland in the northeast United States is what’s owned by municipalities (parks and public landings) and that which is being protected by land trusts. Here in Maine, insult is added to injury because many of these waterfront homes are vacant much of the year; we have the largest percentage of second homes of any state in the nation.

Every morning, I hike up Beech Hill in Rockland. I couldn’t do this without land trusts; my route takes me from Maine Coast Heritage Trust land into Coastal Mountains Land Trust property.

Maine has less public parkland than any other northeastern state. It makes up for that with public land trusts. There are more than eighty of them statewide, conserving more than 12% of the land mass, providing over 2.34 million acres of publicly accessible land and more than a thousand miles of recreational trails. That’s in addition to preserving wildlife habitat, farmland, and working waterfronts.

The age of governments acquiring large swathes of public parkland seems to be over, making land trusts more important than ever. But part of that has to include a willingness to share—to support them financially, with volunteer labor, and by being generous about sharing infrastructure.