Sometimes we do work that is very important to us, but the public reception seems lukewarm or nonexistent. It feels like you’re shouting down a well for all the good it does.

That happened to me when I finished my series on misogyny. I felt very bleak when it was closed down after a few days. Now I realize you can’t judge the public’s reaction by the feedback you don’t get. Still, silence is terrible.

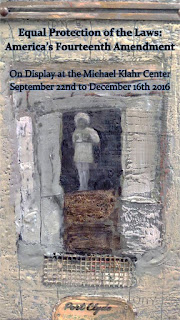

Barb Whitten was a tad dispirited on Friday night after her opening for The Usual Suspects. Attendance was very low. I was being my usual annoyingly-positive self, pointing out that there were office buildings along Water Street and people didn’t need to go inside PopUp 265: A Fresh ArtSpace to see the work; the whole installation was visible from the street.

I told Barb about a workshop student of mine who had commented on my blog post about her show:

“This will be an interesting and thought provoking art opening! Art reflects life, and helps us to empathize and consider the rights and the wrongs that so many in society are experiencing today. I would like to be able to go to this opening, just to talk with and listen to others, and reflect on the issues together. It could be scary and messy but we all need to face the messes our country is experiencing and pray for God’s wisdom as to how to heal our land.”

She couldn’t be at the opening, but she’d told her Facebook friends about it.

Sunday, Barb got a phone call from a perfect stranger, who said:

“I saw the number on the window and just wanted to call and tell whoever was responsible that I think it’s one of the best things I’ve ever seen and a really good way to address and call attention to the things that are going on in our world today.”

And then I got an email from a reader, which said, simply:

“Brilliant work. The whole planet is still in shock, confusion, disbelief.”

This is a three-part message, then.

If you see art that moves you, talk about it. It makes a difference to the artist when the audience is engaged. He spent days, weeks or years creating his or her half of the dialogue, and we’re all cheated if it turns into a monologue.

Art really is more than painting pretty lighthouses for money. I make no apologies about painting landscapes, but there is a subtext to art. It can’t be jammed solely into an economic impact statement.

Don’t assume that if you don’t get immediate feedback to your art, nobody is listening. Because I write this blog, I’m in a position to hear a lot of comments. People are far more engaged than you’ll ever know.

Addendum: The Rochester (NY) Democrat & Chronicle recently interviewed me about figure model Michelle Long. It’s a nice piece and can be read here.