In the absence of a world-class volcanic event, we can expect a typical, stunning coast-of-Maine summer. What better way to spend it than painting outdoors?

There’s been only one time in American history when

summer failed to show up. That was 1816, and it was caused by the eruption of Mt. Tambora in the Dutch East Indies. It was an event that had spectacular cultural repercussions.

In the northern hemisphere, grain crops failed. There was widespread famine for man and beast alike. Horses starved. That led to the invention of the

velocipide, predecessor of the modern bicycle.

Here in the United States, famine spurred the westward expansion. Starving farmers in New England left for western New York and the Midwest, hoping for better weather and richer soil. The cataclysm sparked a religious fervor that created the

Burned-Over Districtof New York. This in turn became a flashpoint for women’s suffrage and abolition.

|

|

Mount Vesuvius In Eruption, 1817, J.M.W. Turner

|

Among those who went west was the family of

Joseph Smith, who relocated to sleepy

Palmyra, NY with rather spectacular results. Both Smith and his mother were prone to religious visions. Was that God or

ergotism from eating spoiled grain?

In the absence of a world-class volcanic event, we’ll have to settle for a typical, stunning coast-of-Maine summer: fresh breezes, blue skies and the soft susurration of the surf on our great, grey granite coast.

My next session of weekly classes starts on May 30. We meet on Tuesdays from 10 AM until 1 PM, until July 11 (skipping neatly over Independence Day). There are two slots open for this session, so if you are interested in taking one, please let me know. The fee is $200 for the six-week session.

|

|

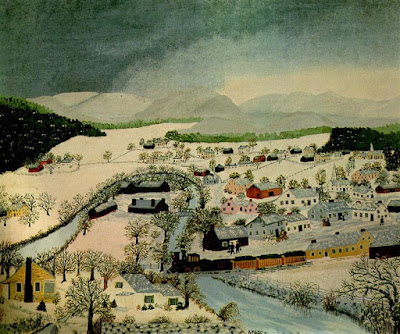

Neubrandenburg, 1816-17, Caspar David Friedrich

|

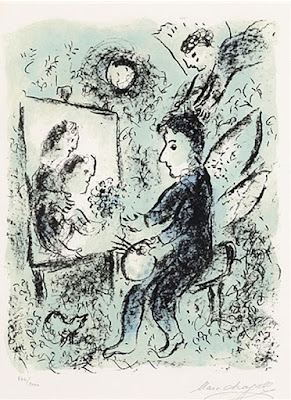

The goal is intensive, one-on-one instruction that you can take back to your studio to apply during the rest of the week. We’ll cover issues like design, composition, and paint handling. We will learn how to mix and paint with clean color, and how to get paint on the canvas with a minimum of fuss.

And, yes, we’ll talk about drawing. If you ever want to paint anything more complicated than marshes, you must know how to draw. As

I’ve demonstrated before, any person of normal intelligence can draw; it’s a technique, not a talent. And it’s easy to learn, no matter what you’ve been led to believe.

Unless the weather is inclement, we’ll paint at outdoor locations in the Rockport-Camden-Rockland area. Painting outdoors, from life, is the most challenging and instructive exercise in all of art. It teaches you about light, color and composition.

That, of course, limits the media you work in to oils, watercolor, acrylics, or pastel, since they’re what is suitable to outdoor painting.

After that, I hit the road in earnest. My summer schedule includes events in Nova Scotia, Maine and New York. (As I tell my family, if you want to know my schedule, you can find it

here.)

For more information about my classes, see

here, or email me

here.