Yesterday I wrote about painters who continued working into their dotage. Today, I give you an example of one who didn’t even start until after most of her peers were dead.

|

|

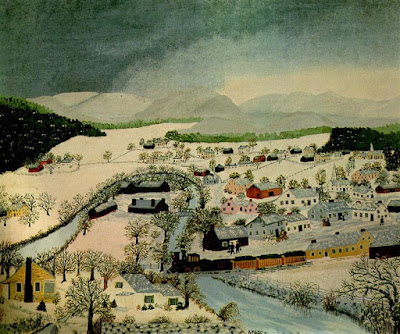

Hoosick Falls, New York, In Winter, 1944, Grandma Moses

|

“The examples you gave yesterday are of people who have painted their whole lives,” a reader wrote. “I won’t have time to learn to paint until I retire. Do you think that is also true for people who take up painting at a later age?”

Leaving aside the idea that other work makes painting impossible (it doesn’t), we have a great example in Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses. She was born in 1860 in Greenwich, New York. She died in 1961 in Hoosick Falls, which is about twenty miles south. She had given birth to ten children, five of whom survived. She and her husband subsisted as small farmers, making much of what they had and doing without. From our 21stcentury viewpoint, her life was hard and limited in scope.

|

|

Wash Day, 1945, Grandma Moses

|

Still, that band of land from Greenwich to Hoosick Falls is arguably New York’s most sublime landscape, a region of soft rolling hills, fertile fields and pretty, old farmhouses. The other place where she lived for two decades, Staunton, Virginia, is in the Shenandoah Valley. It could be described exactly the same way. Both are places where rich urbanites come to vacation and appreciate the beauties of nature, but where the locals struggle to keep the house painted.

Grandma Moses did not take up painting until she was 78, but she showed an inclination toward art for her whole life. She had rudimentary art lessons in the one-room schoolhouse she attended (now the Bennington Museum in Vermont), and access to art supplies from the family who hired her as a farm hand at the age of twelve.

|

|

Mt. Nebo On The Hill, crewel embroidery, 1940, Grandma Moses

|

She produced quilts, dolls, and much crewel embroidery. Her unique painting style resonates with the values of her needlework, which in turn was influenced by the Currier & Ives lithographs of her childhood. Long before she was a painter, she was embroidering landscape paintings of her own design. In fact, she only took up painting when arthritis made holding a needle too difficult.

Moses was discovered by art collector Louis Caldor, who saw her work in the window of Thomas’ Drug Store in Hoosick Falls. Three of the paintings he bought were then included in the Contemporary Unknown American Painters exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1939. Two one-woman New York shows immediately followed. This began Moses’s meteoric rise in the art world. By 1943, there was an overwhelming demand for her paintings.

Her homespun viewpoint contrasted sharply with the abstract-expressionist Zeitgeist of post-war intellectual America. She was popular for all the same reasons her friend Norman Rockwell was popular. By the middle of the 20th century, there was a noticeable split between the cognoscenti and the middle classes in terms of values and mores. It has only become wider and deeper today.

Most of Grandma Moses’s paintings were done on cardboard and are relatively small. She painted her scenes first, and then inserted figures going about the daily work of farm life. She didn’t draw from life or photographs, but from her own fertile imagination. Because of this, her paintings are reminiscent of the Labours of the Seasons from medieval Books of Hours.

|

|

Country Fair, 1950, Grandma Moses

|

She belongs in the pantheon of naïve painters because she was self-taught, but to say that she was in any way primitive is risible, considering what has followed in the art world.