Can objects acquire a vibe from the way they are used and treated? Boats have personality, and it comes from their pasts.

|

| Thaw, by Carol L. Douglas |

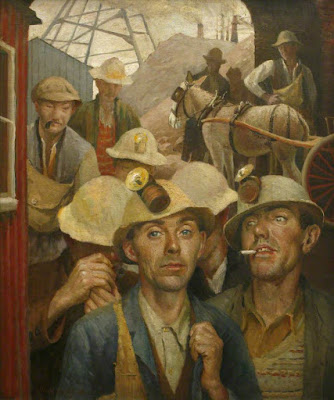

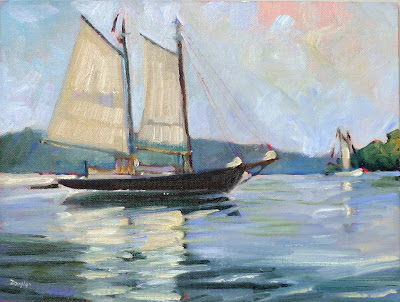

I woke at 3 AM redrafting the bow of the American Eagle in my sleep. I didn’t start her from a measured drawing, but after an internal fight about composition. The winch shed at the boatyard was trying to take over the painting, as it did last year (below). But the fight sapped my determination to draw methodically. I ended up going directly to paint. The results are, perhaps, less accurate and more expressive than usual, and I was working that out in my sleep.

American Eagle is my favorite boat in local waters, but I feel I’ve never really done her justice in paint. She is very graceful and bears the imprint of many loving hands. Launched in 1930 as the Andrew and Rosalie, she’s been captained since 1984 by John Foss, who is a meticulous craftsman. American Eagle comes out of the water looking better than some boats do going back in. In modern parlance, she has good juju.

|

| Winch (American Eagle), by Carol L. Douglas. What a difference sun makes! |

An example of a schooner with bad juju was the

Amistad. Its case would go to the US Supreme Court and pit the sitting president against his predecessor.

By 1839, the United States and most other American governments had abolished the slave trade. Since slavery itself remained legal, however, the temptation to smuggling was strong. In the spring of 1839, 53 Sierra Leone captives—49 adults and four children—arrived at the depot of Spanish slave trader

Pedro Blanco, who was one seriously bad dude. Most of the captives had been kidnapped, although some were war booty. They were part of a cargo of 500 people sent to Cuba on the purpose-built slaver,

Tecora. The individuals in question were purchased as laborers for a sugar plantation near

Puerto Principe.

|

| American Eagle is a well-cared-for boat. |

On the night of June 28, Amistadleft Havana, intending to run past British patrols. She was not built as a slaver; the captives were chained in its cargo hold. And they were abused. The cook, in particular, delighted in implying that they would all be killed and eaten when they reached their destination.

Led by a farmer named Joseph Cinqué, the captives revolted. Using cane knives they found in the hold, they bludgeoned the cook to death and killed the captain. Two crewmembers escaped by canoe, and the cabin boy absented himself from the melee. Two others were ordered to sail the boat back to Sierra Leone.

Landlubbers, the Africans didn’t notice that the crew were sailing them north instead of east. The boat wasn’t provisioned for a long journey, and dehydration and dysentery took their toll. In all, the Amistad traveled 1400 miles before hauling up on Long Island. The surviving slaves were taken to Connecticut, which was still a slave state, and imprisoned.

|

|

From A History of the Amistad Captives, 1840. New Haven, Connecticut: E.L. and J.W. Barber, Hitchcock & Stafford, Printers.

|

The case was a legal morass. It appeared stacked against the Africans. The naval officers who captured the boat claimed it and the human cargo as salvage. The slavers wanted their property back, falsely testifying that the Africans had been born in Cuba and were not subject to the slave trade prohibition. The Spanish and US governments wanted the Africans returned to Cuba, where they would face death. Anticipating victory,

President Van Burensent a Navy ship to hustle the Africans away before abolitionists could file an appeal.

No appeal was necessary. The Hartford court ruled in favor of the African prisoners. Our government pushed the case all the way to the Supreme Court. By then, former

President John Quincy Adams had signed on as counsel to the Africans. Adams accused Van Buren of abusing his executive power. In March 1841, the Supreme Court decided in favor of the slaves, and they were free to leave—except that they had no resources. Northern abolitionists raised their fare to go home.

On November 26, 1841, the 35 surviving former slaves, accompanied by five missionaries, boarded a boat bound for Sierra Leone and freedom. The Amistad was purchased by Captain George Hawford of Newport, RI, who returned it to cargo service as the Ion. It passed out of history somewhere in the Caribbean.