Create a drop-dead painting from a so-so scene.

|

| Wreck of the SS Ethie, by Carol L. Douglas |

Certain places are fascinating for something other than their pictorial value. The angle, the light, and the setting aren’t conducive to a great composition. An example of this was the wreckage of the

SS Ethie in

Gros Morne National Park in Newfoundland. This is a lovely shipwreck story featuring a dog and a baby, but

I’ve told it before.

I’d driven up the Great Northern Peninsula specifically to paint this wreck (and to visit the Viking site

L’Anse aux Meadows.) When I arrived, I realized it was nothing more than a beautiful cove with a debris field spreading for thousands of feet along a rocky shore. There was no hulking wreck to paint, merely broken things lying around—much like my parents’ barnyard, in fact.

|

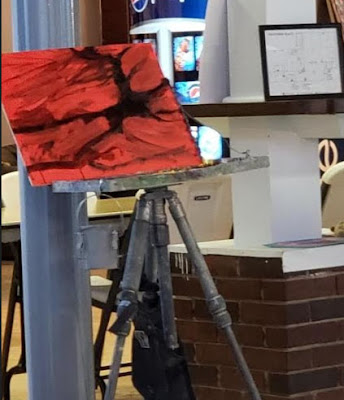

| The actual debris field looks like this. |

Hurricane Matthew was bearing down on us in the form of a blizzard, so I took photos and completed the painting elsewhere. However, I’ve used this technique successfully in

plein air painting as well.

The cove itself is beautiful, and I could have painted a nice anodyne scene of it—lovely, but saying nothing about the wreck. I could have done a close up of one bit of machinery. Instead, I created an abstraction and fitted the details in to it. I do this whenever I’m feeling blocked, either because the subject matter isn’t fitting naturally, or because I’m too anxious.

|

| Initial abstraction for Ethie, based on the word Maelstrom. |

To do this, I improvise a series of shapes on a large canvas, much as if I were going to paint a non-representational painting. The only guidance I give myself is a word. In the case of the wreck, the word was

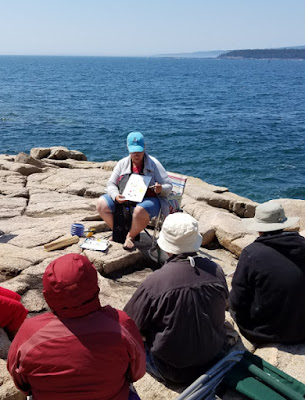

maelstrom. When I demonstrated this technique last week for the

Bangor Art Society, the word was

mourning. Another painting I did recently started with a phrase,

Dwight’s school bus. It was nonsensical; my son walked to school. That word is generally inspired by place or events, and it’s surprising how often the painting ends up reflecting the word I started with.

|

| After the Bangor Art Society decided this was a tree, I turned it that way and started making it into one. Photo courtesy of Teddi-Jann Covell. |

I start this process with a line. In the Bangor painting, it was a flat, thick line that crossed the canvas. In the Ethie painting it was rounded and rollicking. I never start this with a sense of up or down, and I often rotate the canvas while I work. This process can be the longest part of a painting. I’m searching for the composition from my subconscious, rather than from reality. Sometimes it’s based on my initial line and sometimes the line gets subsumed into something else entirely.

When the abstraction is done, I rotate the canvas to see how it might represent something real. At the demo, I asked participants to identify things they saw in my abstraction. Suggestions came fast and furious. I’d had them draw alongside me, so I then asked them to identify things they saw in their abstractions. Total silence. I asked them to trade with their neighbors and again the room was full of suggestions.

There’s a lesson here. We’re born with the capacity to recognize objects in abstract shapes; it’s part of what makes us intelligent and aware, and keeps us safe. A half-seen shape tells us, almost instinctively, when we belong on high alert. But we moderns tamp that down. We allow subliminal shapes to appear in our drawing, but then resolutely refuse to recognize them. That’s where turning the canvas is so helpful. The mind no longer sees it as ours, but as something new.

|

| My demo painting for the Bangor Art Society. It’s not finished to a level I aspire to, but I was getting tired. |

Once I find the objects in my abstraction, I hew to them fairly tightly, converting them into figurative art. But I don’t always solve all the corners of my paintings at the first run. After I’ve drawn in one thing, another suggests itself. And sometimes I change up passages on the fly.

“I feel like I had to understand a lot about light/shadow, perspective, and value before I could do an invented landscape with any authenticity,” a painter commented. This is true, but we all know more than we think we know. And painting from memory is a great way to expand one’s visual memory.

Furthermore, it’s not necessary to do this totally from memory. Try it outdoors, subbing in that rock over there or that tidal pool over there. You’ll end up with a sense of the place, rather than a literal transcription of the place. If you use photo reference, don’t start adding details until you’re well along in the design process. Remember that reality should always be subservient to design.

This reaching down inside yourself is difficult business. But it’s worth experimenting with. I hope you’ll try it and let me see your results.