Overall, the shows I’ve done this summer have been flat, so it’s time to rethink my strategy.

Where is the art market going? This is a question I ask myself every year at this time. It’s more important this year than ever, since my same-event sales have been flat.

I had an interesting conversation with artist

Kirk McBride, after an event I’ve been doing for six years seemed to let all the air out of its tires. “I think there are too many

plein air festivals,” he said. He may be right. They’re in every town, and the smaller markets can’t support them year after year. That doesn’t mean the model is bad; it means the market needs adjustment.

(An important caveat: an individual show can buck all market trends, and there may be regional differences in how your own shows are going. It requires a lot of input to decipher what’s happening, which is why I’m asking for your comments below.)

But here are some sobering facts from

Artsy, collected in 2019:

Adjusted for inflation, the global art market shrank over the last decade. It totaled $67.4 billion in 2018, up from $62 billion in 2008. However, these are nominal figures, not adjusted for inflation. Do that, and we see a market that’s shrunk from $74 billion to $67.4 billion.

To compare, global luxury goods grew healthily. In adjusted dollars, they went from $222 billion to $334 billion in the same time period. In some ways, a Hermès bag is more useful to a person who already has everything. It’s portable, easy to change, and you can store a revolving collection in the space that a painting takes up.

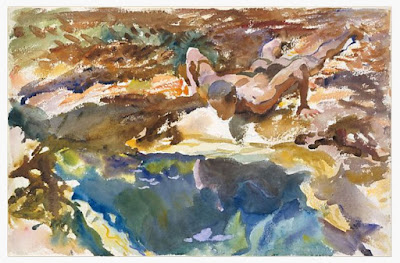

|

| Midsummer, by Carol L. Douglas, currently on hold. |

Over that same decade, the global economy roared, with global domestic product increasing from 3.3% to 5.4%, according to the IMF. That means art sales should have risen. Instead, just the costs of doing business—rent, materials, and time—increased.

I live in a boom market for galleries. Mid-coast Maine—led by Rockland—has been an amazing success. Nationwide, we’re seeing galleries surviving better than small businesses in general. However, we aren’t seeing a lot of new galleries opening.

Colin Page’s new gallery in Camden is one of the wonderful exceptions.

I looked into buying an existing gallery earlier this year and walked away. I still might do something similar, but it won’t involve expensive real estate or labor costs. I’m not passionate about selling art, just making it, and that’s not enough to carry a business.

|

| Ottawa House, by Carol L. Douglas, currently on hold. |

There’s been a significant change in the model of selling art. We’re no more immune to globalization or to the internet than any other industry. It’s time to face facts: while our educational institutions threw away technique starting in the 1960s, it was always being taught in Asia. Those painters have as much access to the on-line market as do we, and their aesthetic may be closer to what’s wanted today.

“Auction houses are going begging for people to buy antiques and art,”

Andrew Lattimore told me last week. “Kids don’t want their parent’s stuff. They want ‘experiences.’”

He’s right, and that impacts artists who sell to the merely well-to-do (vs. the biggest money players, who are buying an entirely different kind of art). The average United States millionaire is 62 years old. Just 1% of millionaires are under the age of 35, and 38% of millionaires are 65 and older. That means that the people with the cash to buy important paintings are of an age to be getting rid of stuff, and their kids don’t want it. Ouch.

Then there are the ethnic patterns of wealth in America. Asian-Americans are the wealthiest Americans, led by people from the Indian sub-continent. Many of these very wealthy Americans are first- or second-generation citizens, so their aesthetic is more attuned to Asia than to traditional American painting.

Is this the death knell for painters like me? Hardly. We need to act as would any other industry in a time of flux. We adapt or die. That means rethinking pricing and reevaluating our sales channels. Perhaps it means a major strategic change in selling.

I’m very interested in your thoughts on the subject. What kind of market did you experience in 2019? What are your experiences with marketing on the internet? Where do you think we should go from here?