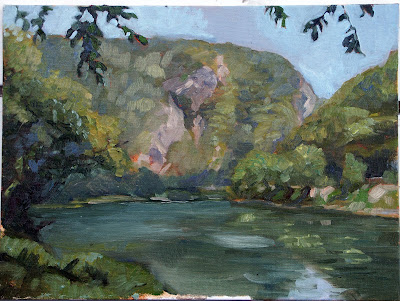

A water gap is a place where a river cuts a notch sideways through a mountain range. Geologists tell us this indicates a river which is older than the mountains it flows through. Pennsylvania is rich in these water gaps, and one of the most well-known is the Delaware Water Gap on the Delaware River between Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

I started this painting around 8 AM or so and finished about 2:45 PM. The light shifted radically during this time. While the copse of trees on the opposite shore was delightful in the early morning, by midday the rock faces across the gap had emerged from mist. I was facing due east, so I knew the sun would track directly above me, gradually illuminating the scene before me.

I started by making a terrible mistake. That plant you see to the left of my palette is New Jersey’s state flower, poison ivy. I had dumped my painting supplies on top of it without noticing. My paper towels went into the trash; the rest of my stuff (and my feet) I washed with baby wipes as well as I could. Nonetheless, I await the rash with trepidation.

I started with a rudimentary sketch for placement. I was working on a small canvas (9X12) and I needed to scale the big landscape down to a workable size.

Next, I refined my sketch into a value study (meaning a sketch of the placements of darks and lights). This study is good for two things. You work out a pleasing composition, and you practice and refine your drawing.

As I continue to study the Canadian Group of Seven, I realize how they framed the landscape in overhanging branches and screens of tree limbs. I have avoided this kind of device because in my hands it looked tacky. But I was determined to try it here. I realized that these branches couldn’t be an afterthought. Instead, they must be part of the original composition, as carefully drawn and realized as the rest of the painting.

I mixed colors for the far hill with my palette knife. To paint with authority, you must mix enough paint. Mixing with a brush is bad for your painting and your brushes. The three colors at the bottom are for the trees—warm highlights and cool shadows on this summer morning. The two colors above are for the rock. Even though the slope hadn’t emerged from shadow yet, my knowledge of the Water Gap told me the faces would be pinkish with violet shadows. My midtone for the rocks was burnt sienna.

I am painting very dry—no turps and no medium, in an effort to keep each color clear and separate from its neighbors. This leads to my second error, about which more below.

I’ve added three higher key colors for the closer mountain, on the right. As you can see, my palette is creeping dangerously close to the poison ivy again.

The problem I mentioned earlier becomes apparent. Because I’m painting very dry, there is little blending going on between paints. In the past I’ve relied on the underpainting to mute my painting automatically, but that wasn’t happening here. I had to go back and “dull” the background colors before I could begin to paint the foreground.

Here is my painting at the point when I quit. I need to resolve the sky a bit and reset the water on the left, which should be more of a grayish olive.