Sailing is a great disperser of cares.

|

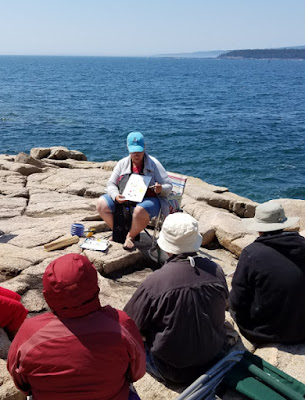

| Practicing painting aboard American Eagle. What a fabulous group of students I had this trip! |

I’m back from teaching watercolor aboard the schooner American Eagle—a little tanned, a little heavier (thanks, Matthew) and a whole lot more content.

Sailing is a great disperser of cares. You’re at one with the boat; you have to be, as ignoring her swings and rolls will cause you to fall down. That puts you totally in the moment, watching the sails, the waves, the shifts in air, and the amazing complexity of 19th century transport technology. Sail power is the original renewable energy resource. American Eagle has been ‘leave no trace’ since long before the slogan was thought up.

|

| We all start at the beginning–how to mix color, how to see color, how to lay it down on the paper. |

The gam—the annual raft-up of the windjammer fleet—was modified this year, as COVID made it unwise to scramble over each other’s boats. Instead, the windjammers dropped anchor near one another off Vinelhaven. A dinghy zipped around with grog. The captains devised a scavenger hunt over the water.

I have a crush on every boat, but I especially have a crush on American Eagle. She’s terrifically elegant and clean-limbed for a boat that started life as a fishing vessel.

|

| Captain John Foss returning from the co-op with fresh lobster for our supper. |

I was rather surprised to see her little sister joining us. That was the Agnes & Dell, proudly flying the flag of Newfoundland and Labrador. She’s a smaller version of American Eagle, with the same proud curved prow and lovely rounded transom. At around 50 feet, she was being sailed by a crew of just two. That’s a manageable dream, I thought. My affections wavered just a tiny bit. But, no, as long as I get to sail twice a year on American Eagle, I don’t need a boat of my own.

|

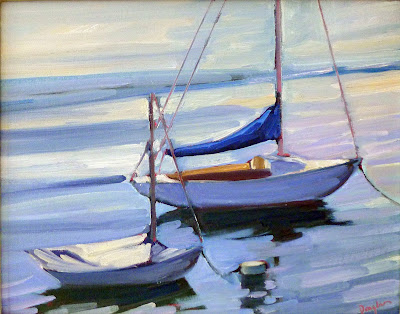

| Agnes & Dell was also built as a fishing schooner. She’s almost as lovely as American Eagle. |

At any rate, I was out there to teach watercolor, not moon over boats. It’s always a great time, and I’m blessed to be able to do it twice a year, in June and September. None of us knew how we were going to return from COVID, but this was a heartening start to a new season.

I had eight enthusiastic students. With a few exceptions, they’re all at the beginning of their artistic journey. It was a special privilege to help them with that. We painted, ate, and laughed—a lot. If you’re interested in the September trip, or any of my other workshops, check my website here. There are still openings.

|

| Dorothy hard at work next to the memorial to quarry workers at Stonington. Even the toughest painters get shore leave. |

On the subject of returning to reality, post-COVID, I’m having an opening at my outdoor gallery on Saturday. Somewhere in the middle of winter I started painting regularly with Ken DeWaard, Eric Jacobsen, and Bjὂrn Runquist. Inevitably, that’s influenced the way I think about and approach my work.

I’m looking forward to sitting down and have a glass of wine with you and talking about the past year. It’s been a sea change for us all, and I want to hear about it from your side, as much as I want to show you it from my side.

Welcome Back to Real Life opens from 2-6 PM, Saturday, June 19 at Carol L. Douglas Studio at 394 Commercial Street in Rockport, ME. The gallery hours are Tuesday-Saturday, noon to 6. Or email me if you want to make an appointment.