My friend Paul Abspoel (here) asked me five questions to be answered on this blog. I apologize for the time it’s taken, but here are the questions and the answers:

Please comment: ‘God is an Artist, but his art is not very accessible’

“Accessible” art has a message we easily grasp. Our response to Creation is visceral and consistent: from the molecular to the cosmic level we react with awe.

As the Book of Common Prayer says, “At your command all things came to be: the vast expanse of interstellar space, galaxies, suns, the planets in their courses, and this fragile earth, our island home. By your will they were created and have their being…”

Who do you consider to be the greatest Dutch painter: Rembrandt van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer, Vincent van Gogh, Pieter Mondriaan or Karel Appel? Tell us what you like about these famous Dutch painters and give us your explanation for the fact that there are so many artistic highpoints in the historic scenery of my flat little country.

Let us start with your last point—why your nation produced so many brilliant painters. Your weather (so damaging to frescoes and tempera) is the reason we have oil painting in the first place. It was developed by the Early Netherlandish painter Jan van Eyk.

Before there was the modern Netherlands, there were the Low Countries. This was the locus of northern Renaissance painting. There was a northern sensibility that was Protestant and Gothic, and which shaped a painting style that was intimate, naturalistic and religious. Unfortunately the Early Netherlandish painters are outside the purview of your question; they include many of my favorite artists.

Your country was birthed as a multicultural, polyglot nation. Flemish capitalists, Sephardic Jews and French Huguenots transformed sleepy Amsterdam into a wealthy world capital. That hybridization was similar to the one which created America, and it seems to work not only for commerce but for culture.

The Dutch Republic was unique in that your wealth was held by merchants and skilled tradesmen, not with the church or nobility. Your bourgeoisie’s tastes ran to portraits, still lives, landscapes and genre paintings, in an “accessible” style.

On to your painters:

I have often wondered how Rembrandt ever sold a single painting, since he cared so little for Dutch virtuosity. His sensitive character assessments, intentional gawkiness, and fluid brushwork were more suited to Romanticism than to his time.

Rembrandt’s work is often subject to crackpot theories of attribution. Art critics can’t believe that someone so great can be so awkward, but it’s essential to his work. There is a Rembrandt at the Frick called “The Polish Rider” (here) which has been the subject of raging debate about authenticity. I believe it is his, and it illustrates how his technical unevenness contributes to the greatness of his painting.

There are only 35 definitive Vermeers known, so we are blessed to have several in the United States. I am always struck by how tiny his canvases were, since he seems to open the window on entire lives.

Vermeer’s genius lies in the way he reins in his superlative skill. Not for him the luscious, overblown still lives of his peers. We understand that he could paint anything, so what he chose to paint matters. He was a brilliant narrator, opening a tiny window into a story or principle. My mother has had a print of “The Lacemaker” (here) hanging in her dining room for forty years; I appreciate the moral tale (diligence and concentration) but at the same time it is also a lovely painting.

There is another Golden Age painter I’d add to your list: Franz Hals. He is known for his virtuosity, and people assumed he painted in one fast pass. Recent analysis shows that he built his work up in the traditional manner and then applied loose brushwork at the top. His hardy, carousing Dutchmen match my inner vision of your country. His “Banquet of the Officers of the Civil Guard” (here) show how gifted he was, but his intimate portraits like this young knucklehead (here) are what I love the best.

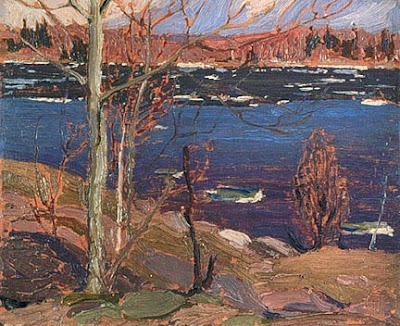

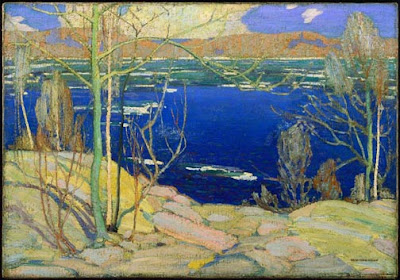

Van Gogh is probably the single most important painter of the last two centuries. He stood between the Impressionists and the Expressionists but there is no easy label to affix to him. There is no theoretical detachment in his color study as with the Impressionists; there is no disregard for subject as with the Expressionists. His work was always yoked to drawing and composition, and it is a mistake to assume he worked in one pass, for his work was carefully considered and developed. His paintings were never intellectual exercises or mindless pastorals. He was not distorting reality, but rather painting his own reality.

I admire his landscape technique beyond words, but I also empathize with him as a failed missionary and preacher. There is no way I can pick an iconic painting for him so I will point out an unusual one: “The Good Samaritan” (after Delacroix, here).

Pieter Mondriaan was interested in Theosophy, which makes sense when considered along with his move from expressionism to intellectual color theory. His grids are nicer in life than as reproductions, since they have a hand-made quality that is lost in photos. They are, of course, beautifully composed. However, I would select the beautiful “Molen Mill” (here) as his iconic painting, even though it’s not what he is remembered for.

Unfortunately, Karel Appel doesn’t do a thing for me. Willem de Kooning was more sensitive, less retrograde, and had a better color sense. But neither belongs in a list of greatest Dutch painters. Sorry.

What is your favourite Psalm? Please also tell us why.

The 23rd. It’s short and memorable. The first three verses are a promise about the Kingdom of Heaven on this earth. The next two describe our special relationship with God. The last one points clearly to our resurrection, as it neatly segues from this life to the next.

What special qualities do you appreciate in your husband and children?

I met my husband at age 15, in high school. We have been married 27 years. He is a brilliant and talented man with utterly no hubris about him. He’s sacrificed a great deal of his personal ambition to support his family, but he’s stoic and uncomplaining. He is not a rigid thinker and therefore my best guide to working through a complex question. He is not particularly reverent, which makes him very funny. And he loves art and history, so we travel happily through life together.

My daughter Julia (18) is an outgoing, entertaining girl with the heart of a missionary. Laura (also 18) is introspective, intellectual, and very loyal. Mary (14) has the soul of an artist, and I think she is most like me: often in trouble, but with a good heart. Dwight (10) is too young to categorize, although I would describe him as affectionate, funny, and unusual.

Outside this interview, what’s the best question someone has ever asked you?

“Do you accept personal checks?”