|

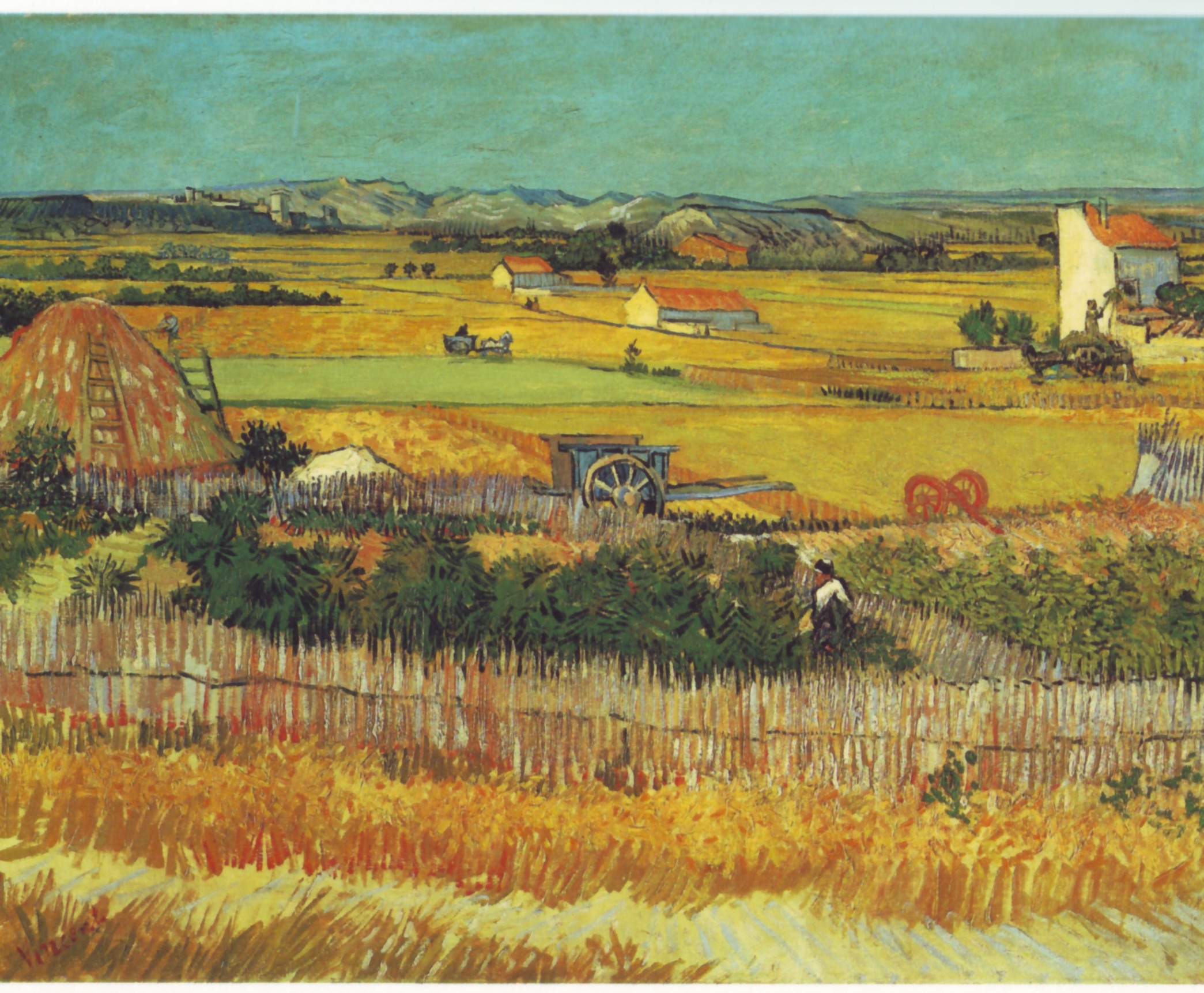

| I can’t imagine why running here makes us think about aesthetics. Since I’ll never paint from a photo, you can enjoy the reflections and shadows now. |

Mary and I are running on the canal bank, discussing opening and delayed adverbs and adjectives. (I think middle school teachers invented them to torture students.) She gives an example: “Gracefully, Carol runs along the canal.” (Heh.)

I stop and stare at her—any excuse for a break. “Why would anyone teach a kid to write in such an antiquated manner?”

Mary’s a writer, and she’s in love with words. “It might be useful,” she protests. “Chiaroscuro might be obsolete, but there must be times you use it.”

I shudder involuntarily. “Never. It would never work with direct painting.”

|

| This is from Gamblin’s very fine explanation of indirect painting, which you can find here. The monochromatic phase of an indirect painting is basically a value study. |

Mary knows that as long as I’m talking about painting I keep running, so she asks me the difference between direct and indirect painting, and how Rembrandt and other classical painters built up their work. Huffing only slightly, I tell her that the artist started with an imprimatura, an earth tone base, and built up successive layers of transparent warm glazes. These were allowed to show through as dark tones in the final work. Opacity was added on the top, as light tones which glowed against the darks.

|

| In the second phase, the artist has added lights, which are also opaques. |

The Impressionists essentially invented an entirely new system of painting—direct painting—where a painting is done in opaque layers rather than built up from transparency. This radical technological shift was possible because modern chemistry was developing so many new pigments.

|

| The finished work allows the imprimatura to show through (although in this example, the artist has muddied the darks and let it show through in the midtones). |

I tell her a bit of my own story: I learned to paint indirectly and was doing it until I went to the Art Students League to study. There,

Cornelia Foss told me, “If this were 1950, I’d say ‘brava,’ but it’s not.” Tough words, but the best painting advice I ever got.

“But why is that?” Mary asks. “What about direct painting made it right for the 20th century?”

I speculate: indirect painting is more conducive to well-reasoned, planned paintings of academic or religious themes; direct painting is conducive to emotion expression. This puts it in sync with the overstimulated, nervous, energetic pulse of modern life.

“It’s kind of like the difference between a home-cooked and a restaurant meal,” Mary says.

I stop and stare again. Really, at times Mary boggles my mind.

“A home-cooked meal takes a long time to prepare. It is often, literally, a love offering,” she explains. “A restaurant meal—even the best of them—is quicker, and is more an expression of what the chef can do.”

Somehow, that goes right to the heart of the matter. Until the end of the 18th century, painters were looking outward—as missionaries of faith and social justice, or as teachers of classical myth and history. We may think those subjects are dated, but they show that the artist was primarily concerned with his audience. After the rise of the Cult of Genius, the artist’s personal vision became paramount.

So I think Mary’s metaphor is apt: indirect painting was a love offering, and direct painting is all about me.

Every day I do one task to prepare for my June workshop in Rockland, ME. Today’s was cleaning the Prius. Meanwhile, what are you doing to get ready for it? August and September are sold out for my workshop at Lakewatch Manor in Rockland, ME… and the other sessions are selling fast. Join us in June, July and October, but please hurry! Check here for more information.