The gender disparity in art is terrible. So why don’t I paint under a nom de pinceau?

|

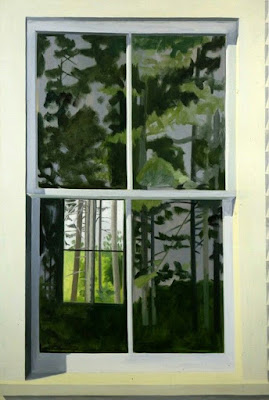

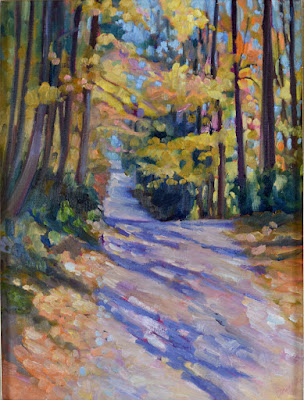

| Autumn Leaves, Beauchamp Point, is one of the non-nude paintings at the Rye Arts Center’s Censored and Poetic this month. |

Last month, when I wrote about the gender disparity in art, a reader asked me why I didn’t believe gender-neutral nom de pinceaus were the answer. I promised I’d answer the question in my following post, but then Russia invaded Ukraine and it seemed like wars and rumors of war were more pressing.

Last night was the opening of Censored and Poetic at Rye Arts Center, which brought the question back to mind.

|

| Kicki Storm, me, and Anne de Villeméjane at the opening. |

The gender disparity is in fact greater than the race disparity in US galleries. According to a 2019 study, an estimated 85% of artists represented on US gallery walls were white, compared to 76.3% in the general population. That is terrible, but a study the prior year found that in 820,000 exhibitions across the public and commercial sectors in 2018, only one third of the works were by female artists. That’s despite the fact that 51% of the US population is female.*

In general, a name cannot tell you whether a painter is white or black. I had a brief chat about this last night with Matthew Menzies, my former painting student. Matt and I both check a lot of the same sociological boxes. We both have Scottish surnames. However, Matt’s not white, although you’d never know that until you met him. On the other hand, my given name tells you immediately that I’m female. I can be rejected in the sorting process.

Last night, Kicki Storm referred to a 1989 art project by the Guerrilla Girls called Do Women Have to be Naked to Get Into the Met Museum? which found that less than 5% of the artists in the Modern art section of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York were women but 85% of the nudes were female.

I’d like to say it’s better now, but a short comparison of the careers of Lois Doddand Alex Katz reveals otherwise. They have oddly parallel careers. Both studied at Cooper Union. Dodd went on to be one of the founders of the Tanager Gallery. She taught at Brooklyn College and Skowhegan.

The Met owns 19 Alex Katz paintings and three of Lois Dodd’s, none of which are on view. MoMA owns one Lois Dodd painting, acquired in 2018, when she was 91 years of age. I lost track trying to count how many of Alex Katz’ paintings they own; there are 137 records.

In light of this, why not hide behind a gender-neutral set of initials, or, even better, a false name? Because to do so is to capitulate to the world, to agree to its assumption that male painters are superior. If my generation doesn’t challenge this assumption, who will?

There’s also the stubbornness of identity. I am who I am, for better or ill. That’s complex; it involves boats and building as much as it does children and grandchildren. Concealing that complexity simply perpetuates gender stereotypes, which I think have gotten more rigid, not less, during my lifetime.

*Every time I read about a massive survey like these, I wonder who has time to count these things.