Being technically accurate frees up your subconscious mind to analyze and interpret what you see.

|

| Main Street, Owls Head, 16X20, oil on gessoboard, $1623 unframed. |

I once took an artist on a long loop to see all my favorite painting sites here in midcoast Maine. “But there’s nothing to paint,” she wailed. She was suffering an extreme case of sensory overload. We all experience this to some degree when we’re forced to buckle down to work. We’re asking ourselves to choose one subject among an infinite number of possibilities. And the obvious and iconic may not make the best (or most interesting) painting.

We all want to jump quickly into painting, but the better path is to spend some time relaxing and looking. I prefer to do this with a sketchbook and a lawn chair. If you’ve spent 10 minutes just drinking in the beauty, and then do four thumbnails of different scenes, you haven’t ‘wasted time.’ You’ve saved yourself immeasurable amounts of work on mediocre paintings, by answering the following questions:

- Where does the visual strength in this composition lie?

- How can the picture plane be broken into light and dark passages?

- How can I crop my drawing to strengthen the composition?

|

| Belfast Harbor, 14X18, $1594 framed. |

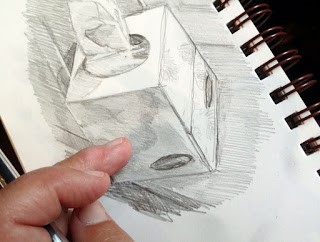

Measurement

At some point, you need to get precise. Fast, loose painting rests on a base of good drawing. If you haven’t been taught to measure with a pencil, start here, hereand here.

People tell me all the time, “I can’t draw a stick figure.” It depresses me, because drawing is a technical exercise, and anyone can learn it, just as they learn to write or do arithmetic.

I recommend the book Sketching from Square One to Trafalgar Square, by Richard E. Scott. It’s a comprehensive introduction to drawing from observation. Books and classes that focus on the interpretive side of drawing are not useful for the artist who needs to get things right, so before you sign up, make sure that teacher, video, or book is actually teaching drawing, not some form of self-analysis with a pencil.

|

| Beach erosion, 8X10, oil on canvasboard, $522 unframed. |

Interpretation

Being technically accurate, oddly enough, frees up your subconscious mind to analyze and interpret what you see. We all paint through the filter of our own experience, values and aspirations. That’s why one artist will edit out the power lines and trash cans on a street scene, and another will focus on them.

But there’s a deeper level at which this happens, and that’s in the colors, forms and shapes themselves. They’re tied to your subconscious. Within the rubric of ‘good composition’ or ‘good taste’ are infinite variations. What you perceive is highly individual, so your interpretation will also be individual.

|

| Marshall Point, 12X9, oil on canvasboard, $696 unframed. |

Reiteration

The first three phases are all essentially input—identifying, measuring, and analyzing the subject you’re painting. The final business of producing a work of art is collecting all that input and restating it on your canvas or paper. If you’ve done the first three steps conscientiously, this last step should be relatively relaxed and free. It should also go quickly. Your own ‘handwriting’, in the form of brush or pencil work, will be unfettered and loose.