My strategic plan for 2022 seems to be in tatters. That’s the price of constant overdrive.

|

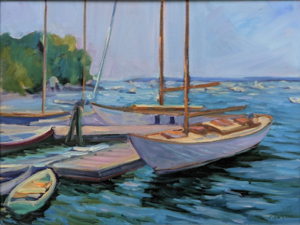

| Skylarking, 24X36, oil on canvas, available. |

At the end of last year, pastor Quinton Self challenged us to stop with the busy work and focus on what matters. That includes moments of rest. He and I are the same psychological profile (with the test scores to prove it), so when he zings me in a sermon, I figure he’s also talking to himself. In February, when he’d just finished a fast-paced, five-week teaching program on top of his other work, I asked him: “so, how’s that Sabbath rest thing going for you, PQ?” He smiled. It’s a constitutional problem for both of us.

Every year recently I’ve said, “this is the latest I’ve ever done my taxes.” This year’s record will stand. I can’t get much later and not file for an extension. That’s a terrible idea; it just prolongs the agony. What’s scary is that I didn’t even think about taxes until I was flying back from Phoenix two weeks ago.

|

| Breaking Storm, 48X30, oil on canvas, available. |

I had coffee with my Canadian pal Poppy Balser last week. I don’t really envy our Canadian neighbors their economic system. However, when I’m calculating income tax, I wish we could streamline our ponderous system and replace it with something like theirs. As a sole proprietor, I keep records on all kinds of things that are irrelevant to the average taxpayer—household repairs, utility bills, and the cost of operating my car.

It’s time-consuming and tedious, and I’m good with numbers. I can’t imagine what it’s like for my math-phobic fellow artists.

Admin is the curse of all sole proprietors. We write our own ads, maintain our own websites, do our own strategic planning, keep books, and somehow churn out a product. I am, for some reason, drowning in admin right now.

|

| Wreck of the SS Ethie, 18X24, oil on canvas, available. |

“Did I ever send you the materials for next year’s ad?” I asked Anthony Anderson of the Maine Gallery Guide yesterday. No, he replied, but if I can get it to him next week, I’ll be fine. I could hire my student Lori Galan or my old friend Victoria Brzustowiczto lay it out for me. Either of them would probably forgive me my hair-raising lateness. However, I don’t even have a clue what I want to say. And that ad is the most important one I’ll run all year.

Being in constant overdrive is corrosive. It forces a person to be reactive, batting balls back out as fast as they come in. Instead, intelligent people are proactive, thinking out a strategy and sticking with it.

I did that at the beginning of the year, by the way. It’s in tatters.

|

| Beautiful Dream, 12X16, oil on birch panel, available. |

But help is on the way. When we’re in overload, things have a way of falling on us and slowing us down. Another Canadian artist friend, Cathy LaChance, put it very succinctly when she was diagnosed with COVID this week: “My turn to be forced to rest.”

Call it the

The problem with frenetic people is that we are sometimes so busy we can’t hear the “still small voice” of God. That’s why it is often accompanied by the wind and earthquake (or COVID)—to get our attention.

I’d rather not wait that long.