Mixing paints is simple if you understand how pigments work.

|

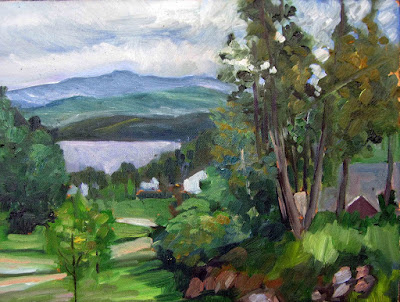

| Fallow field, 12X16, oil on canvasboard, available. |

In theory, you can paint with just four pigments: red, blue, yellow and white. For beginning painters this is sometimes a good idea, because it’s the fastest way to learn color management. It simplifies the thought process so you have only one decision to make at a time, and it is easier to get a more unified color scheme.

But there is a limiting factor, and that’s the impurity of pigments. They all have overtones that muddy them up in certain mixes. That’s why your local paint dealer uses many, many more pigments than just red, blue, and yellow.

Claude Monet’s palette shifted over time, but included these paints:

- Chrome yellow

- Cadmium yellow

- Viridian green

- Emerald green

- French ultramarine

- Cobalt blue

- Madder red

- Vermilion (red)

- Flake white

- Ivory black (before 1886)

These are sets of paired pigments. That means he has a warm and a cool of each color, plus black and white.

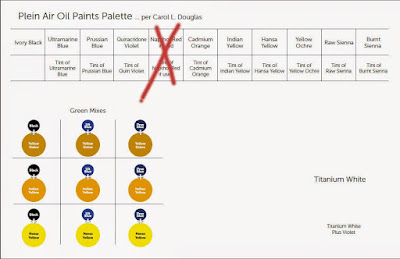

I use paired primaries as well, omitting the green but adding in some other earths. (Here are my supply lists for oils, acrylics, and watercolors.)

The distinction between warm and cool colors has been important in painting since the Impressionists. Warm colors are said to be hues from red through yellow and cool colors are said to be the hues from green through violet. Each hue around the color wheel also has a warm and a cool version.

There’s no factual hot or cold point because this is just a poetic description that works. Much of what we believe about the psychology of color is hocus-pocus, based on the teachings of 19th century cult leader Madame Blavatsky. However, it’s true that if the light is what we call “warm,” the shadows are what we call “cool,” and vice versa.

|

| Paired primaries are simply warm and cool versions of each color. |

When we say that lemon yellow is cooler than cadmium yellow deep, we mean that if you are trying to mix a greenish yellow, you’ll get a clearer shade with the lemon than you will with the cadmium yellow deep. The warm-cool language is just a convenient way of saying that.

Different pigments may look the same when squeezed out of the tube, but there the similarity ends. Pigments are impure, and you have to learn and work around those impurities.

To better understand color space, watch Gamblin’s excellent video on the subject, here.

|

|

Three blues that look similar out of the tube, but behave very differently. The ‘glaze’ on the left is the undertone. Courtesy Gamblin paints. |

Mass tone is the color a pigment is straight out of the tube, dense and unmixed with another color. No real-world pigment, however, is as pure as a color on a video screen. While two pigments may look the same to the naked eye, their behavior when mixed can be radically different.

Undertone is the color revealed when a paint is spread thin enough that light bounces back up from the substrate. Some pigments are fairly consistent when moving from mass tone to undertone. Others have significant color shifts. Not understanding those undertones tones can lead to muddy mixes.

Ultramarine, Prussian and phthalo blue are colors that shift radically from mass tone to undertone. They’re all so dark out of the tube that their differences aren’t apparent to the naked eye. But dilute them, and you’ll find a wide range of blues.

Undertones are why buying “hues” instead of pure pigments can be such bad value. Take, for example, cadmium red hue, which is usually a napthol red with a small amount of white added. Out of the tube, the two paints are indistinguishable, but they mix very differently.

To see a pigment’s mass tone, put a small dab of paint on a smooth white board or glass palette and draw it down with a knife, creating a uniform, solid stripe that completely obscures the painting surface.

To see the undertone, draw the sample down again so it is translucent. You should be able to see minute variations in the color, and in the covering power.