Ten years ago I wrote about teaching Amy Vail to draw. She’d made the cardinal error of telling me she “lacked the gene to draw.” Since I know there’s no such gene, I challenged her to let me teach her, and she made great strides in just one week. Drawing is not a magic trick; it’s not a talent. It’s a technical skill no different from reading, writing or arithmetic.

I know people who paint by tracing photos or photo-montages, but that prevents the non-linear part of the mind from getting involved. Art has always been about deeper things: reflection, aesthetics, ideas, feelings, spirituality and other forms of higher-order thinking. It makes no sense to shut out the part of your mind that processes these.

I’m writing syllabuses for my January-February classes (and I’m sorry, but they’re both sold out). This is the first time I’ve taught drawing outside the context of painting. What is important and how do I teach it?

Observation Skills

The ability to closely observe and analyze a subject develops hand-in-hand with the physical act of drawing. One can photograph a scene without paying too much attention. Drawing and painting from life is how skilled realist painters sort out what matters. The best way to really see something is to draw or paint it.

Details are almost the least-important part, although it’s amazing how much one glosses over them until one actually sits down to draw. What really matters is proportion and the relationship between elements. That comes down to distance and angles. That is why painters can get away with leaving out detail if they get the proportions and relationships right. Anyone interested in abstracting the landscape had better have top-notch drawing skills.

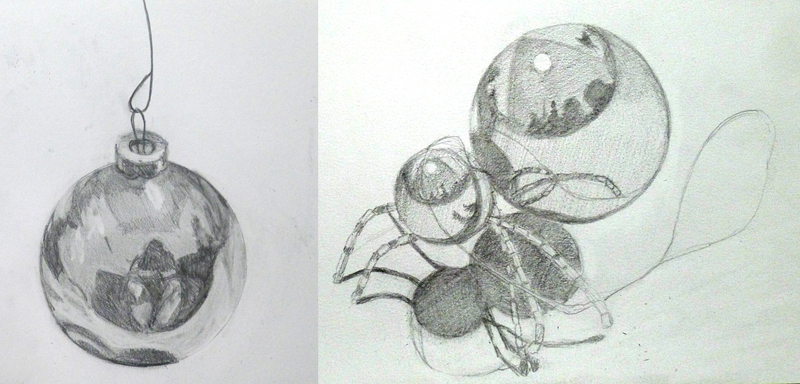

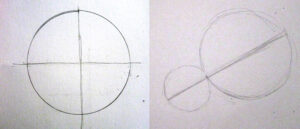

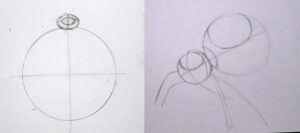

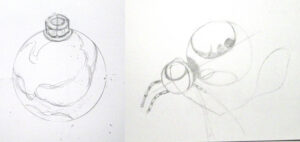

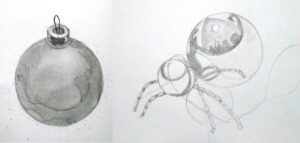

Basic Shapes and Forms

Almost every complex shape is a combination of basic shapes like cones, boxes, spheres and columns. For example, the spinet piano next to me is fundamentally a tall box with another boxlike structure (the keyboard) attached to the front and supported by two columnar legs. Get the size relationships of those big shapes right, and the fluting and scrolls are almost extraneous.

In their 2D form that means circles, squares, triangles, and ellipses. That doesn’t mean, however, that you get to ignore dimensionality, which leads us to…

Perspective

Everyone should learn how 1-, 2-, and 3-point perspectives work, and then never use them again. They’re a theoretical construct that shows you how to avoid errors, but they’re not ‘true’. The vanishing points in the real world are infinitely distant, and that’s hard to achieve on paper. However, understanding perspective will save you from lots of mistakes.

Volume and shading

Yes, one can imply volume with line drawing alone, but shifts in value tell a broader story. They will also form the basis of painting composition.

Expressive mark-making

This is where drawing suddenly gets fun. Expressive mark-making takes time to develop, but experimenting with different line weights and styles is the first step in that exploration.

So how do you start?

Drawing is the cheapest and most liberating of all media. All you need is a sketchbook (this is the one I use, and I go through them like candy), a mechanical pencil, and some kind of straight-edge.

Then start drawing every day. It’s that simple. This is the text I recommend to those who like learning from books, but you can also find a lot of free instruction on this blog.

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.