Street art

Street artist Banksy is believed to be behind a ‘mural’ painted in Finsbury Park in London. It is a spatter of green paint that implies the leaves on a nearby pollarded tree. Banksy is, of course, a favorite of the high-end art market. He’s the guy who once got $1.4 million for shredding a painting.

Meanwhile, Chris Kanizi, 65, who owns the Golden Chippy, also in London, has been told to paint over a mural that he paid to have painted on the side of his shop. It’s a fish, and it reads, “Fish and Chips: A Great British Meal.”

“Why are planning laws, not to mention property laws, continually bent in order to favour the pseudonymous artist [Banksy] when they continue to come down so heavily against anyone else who has a go?” asked columnist Ross Clark “Banksy is not just tolerated: some of his works have been listed, so the owners of the buildings on which they have been sprayed couldn’t even remove them if they wanted to.”

The same conversations happen here in the Land of the Free as well–here in Arlington, VA, and here, in Conway, NH, to cite just two examples.

Is it art or vandalism or just plain advertising?

America has a long relationship with roadside art, which even lent itself to a style of architecture called Googie. Drive down Route 1 through Saugus, MA and you’ll pass signs from the heyday of Googie. Some of the businesses are gone, but the signs remain. After 70 years, they’re protected landmarks.

So why do we stop people from building roadside commercial art today? Ross has a simple answer: advertising art is for oiks, not the well-bred fans of Banksy’s art.

Art or vandalism, redux

Those of us who love art have been troubled by the recent trend of protesters damaging works of art. In Britain, where this is beginning to look like a national sport, prosecution has been hindered by the Criminal Damage Act 1971. If the perpetrator believes the owner would have consented if he or she understood the circumstances, then the damage is excused. This codifies the common-sense idea that if you see a baby in a hot car, you’d be right in smashing a window to rescue it.

If that was your Velázquez that was just destroyed, well, you just didn’t properly understand the threat of climate change, and now that you do, it’s fine.

Yesterday Lady Chief Justice Lady Carr delivered a judgment on protest law that should close that loophole. Perhaps it will help hurry this fad into obscurity before more Constables, Van Goghs and other priceless pieces of our patrimony are damaged.

Those dark nationalist feelings

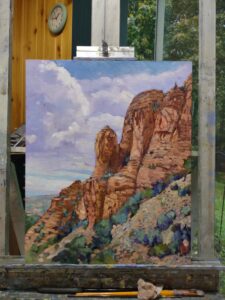

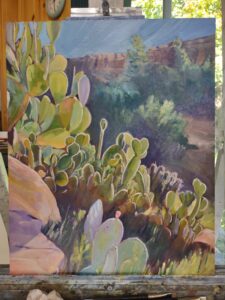

Landscape painting has always been about pride of place. We love the Hudson River School in part because they’re so optimistic about America’s heritage and destiny, on which rested their themes of discovery, exploration, and settlement. The Canadian Group of Seven painted the energy of the Great White North, and helped establish the Canadian art ethos. Joaquín Sorolla was a proud Spaniard; Anders Zorn was a proud Swede.

The Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge has decided that British landscape painting has a dark, nationalist underbelly. A new label in its landscape collection reads:

The countryside was seen as a direct link to the past, and therefore a true reflection of the essence of a nation.

Paintings showing rolling English hills or lush French fields reinforced loyalty and pride towards a homeland.

The darker side of evoking this nationalist feeling is the implication that only those with a historical tie to the land have a right to belong.

Think of that next time you go outside to paint.

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.