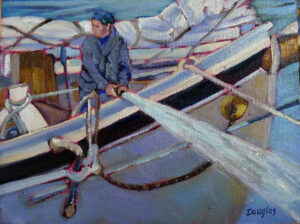

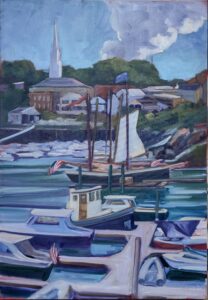

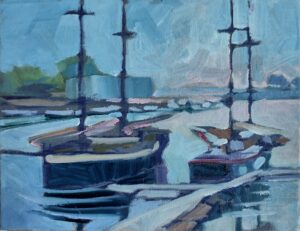

“There have been few more momentous weeks in British history, or indeed in world history,” Bruce Anderson wrote in the Spectator. The Queen’s funeral coincided with the rout of Russia. I missed it all. I was coasting around Penobscot Bay on the schooner American Eagle, teaching watercolor, as I do twice a year.

I would normally have watched the Queen’s funeral, either in real time on the internet, or by flipping to the BBC every five minutes as I worked. I don’t watch television, but I do read voraciously. I was raised with The Buffalo News delivered every afternoon. Reading the news is a hard habit to break.

Back then, the news was structured. The front section gave us international and national news of import. The second section was local news. Then living, and then sports. After that came the auto ads and classifieds. All neatly segmented and focused on a local audience. Those of us who wanted more could take the New York Times on Sunday—back when it really was the nation’s ‘newspaper of record.’

One would occasionally get a ‘Florida man’ story—if it was sufficiently amusing—but paper and ink and the trucks to drive them around were expensive. Editors carefully selected what went in our local paper. Moreover, we read it and then we set it aside. We didn’t come back every hour for more.

Today my phone tells me ‘The Real Reason Why Prince Harry and Meghan Markle Allegedly Went Back to Montecito Fuming’. I can read about a woman who faked her own kidnapping, a teenager shot to death by someone who thought the kid was a political extremist, another teen who died in a football game, or a Missouri mother looking for the remains of her murdered child. No wonder so many Americans take antidepressants. The world isn’t inherently any worse than it used to be, but all its ugliness is being served up to us constantly.

Out at sea, there is only spotty signal. (Unfortunately, it’s improving over time, as more islands get coverage.) My husband—an electrical engineer—once told me how he could fix that empty space. I looked at him horrified. “Don’t even think about it!” As long as our captain can communicate his position to other boats and the Coast Guard, that’s enough contact.

While the world revolved without us this week, we painted. A Hurricane Island crew stopped and talked to us about their scallop research. We watched two bald eagles doing an amazing dance over a bit of ledge. A finback whale breached behind our stern. Porpoises did their lovely cartwheels. Seals were everywhere; so were schooling fish and the gulls that eat them.

Heather broke up her painting by fishing for mackerel. She caught five.

It was unusually cold for September, but that didn’t make it bad weather. It mizzled, it fogged, the wind came up and went down, the sky was grey, then slate blue and violet, and finally brilliant blue. We picnicked on lobster, corn and fresh vegetables.

Finally, on our last morning, it came down in buckets. We watched it from beneath a deck awning while eating hot biscuits and frittata, wearing waterproofs.

I can’t say why, but art is restricted by anxiety. Nervous tension stops us from reaching our real potential. There’s something about the ocean that releases that, and frees us from the need to produce something ‘great’.

By my last day aboard, I find that I never reach for my phone except to take photos. The real challenge is to bring that home, to stop being so plugged in. Yes, we need to be informed citizens, but a little bad news goes a long way.