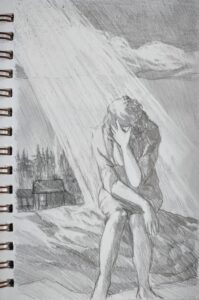

The ancient Greeks used ποίημα (poiēma) to describe workmanship. It comes down to English as poem and poetry. Poesis, which means bringing something into being that did not exist before, is another derivative.

It’s no surprise that ancient Greeks thought of creativity in poetic terms; they were masters of verse. We do the same thing today, letting language romp across various art forms willy-nilly. Composition and dissonance, for example, mean the same thing to a musician as to a painter.

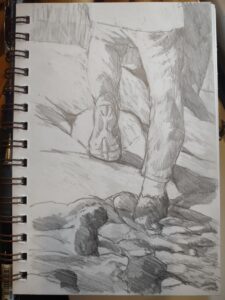

That’s because the structure of art is oddly consistent across genres. My bass player husband can pick up any string instrument and coax decent sound from it, because the principles are universal.

There are exceptions, of course. “What is the equivalent of a sketch in photography?” Ron Andrews mused in response to this post. Ron’s right about static photography not needing sketches, but storyboards are just sketches for moving pictures.

You don’t know what you don’t know

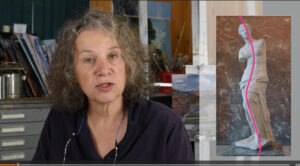

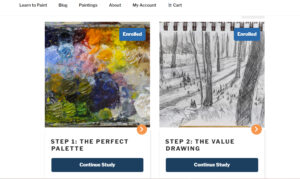

At the beginning of this year, I set out to make a series of online classes about painting. I want to get through the seven steps of a painting by the end of this year. I’m almost done with step three, composition. It’s been a doozy. The lesson is long and complex, but so is the subject of composition.

Just the brain dump would be challenging enough. On top of that, I’m still learning the medium. I have no director, so I’m learning to speak slowly and naturally to a camera in an empty room. I’m learning to do voice-overs and tinkering with ways to demonstrate technique. I’ve learned to edit audio and video on three different platforms.

Then there are the exercises and quizzes. To write them is easy; to make them work interactively online is more difficult. Thank goodness for Laura Boucher. She’s my operations manager, daughter, and software guru.

Look to the experts

I don’t watch television or movies and I’m too old for Tik-Tok. To overcome this, Laura has me studying YouTube videos. Sandi Brock is a middle-aged sheep farmer from Ontario with close to a million subscribers. She’s an improbable influencer. I learn a lot from her.

The most liberating lesson is that people really don’t care about my flat Buffalo accent or wrinkles. To some extent, the artifice of perfection is irrelevant in contemporary social media. People find their own tribe and ignore the rest.

Painters today have incredible resources compared to the last century. My father taught me to paint, but for most people, learning opportunities were limited to what the local art gallery had on offer. If, like Bob Ross, you were interested in realism in a town where abstraction was king, tough. You were out of luck.

Today you can go online and study with just about anyone, including me. You’re the captain of your own ship, for good or ill.

I’m a convert

When I was young, I took voice lessons. I still love to sing, but my voice is a mess. Right now, I’m looking for a place to take voice lessons online. The beauty of this scheme is that I don’t need to show up at 6 PM on Tuesdays; I can do the lessons whenever I want.

Three years ago, at the start of COVID, I fought the idea of teaching online. Today I’m a convert. The proof is in the pudding, and my Zoom classes have proven more effective than ‘real life’ classes in creating professional artists, and almost as effective as intensive workshops.

And that’s why I’m, at age 64, learning a whole new form of ποίησις. The medium may change, but the impulses of creation are universal.

So tell me in the comments, what new skill are you working on?

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.