Collaboration is not usually an exercise for plein air painters, but occasionally an arts organizer will come up with a madcap scheme where teams of four will create a painting together in a short period of time. This is something that Sedona Plein Air does; the paintings are sold at $250 and the money used to raise funds for the art center. The staff likes to throw us curve balls, like ‘paint with your mouth’ or ‘paint with a packing peanut’. That said, the difference between last year’s and this year’s paintings was amazing. It all came down to the ten minutes we were allowed for planning.

Design the project

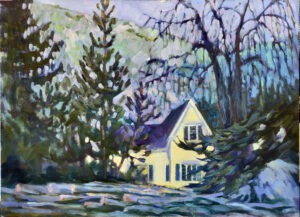

We were divided into groups and given ten minutes to design and plan our 18X24 painting. That included choosing the subject, designing the composition, and setting the order in which we would paint (which defined each participant’s tasks). Jacqueline Chanda transferred our sketch to the canvas, I did the color-blocking, Kathleen Gray Farthing built up form, and Lydia Gatzow did the finishing flourishes. We each had 15 minutes for our section.

Maintain open communication

A madcap project like this doesn’t require Zoom calls, emails, or texts, thank goodness. Communication proved very simple; although we expected each other to fetch and critique as we went, there was little need for the latter. We all did our sections with a minimum of fuss.

Set realistic deadlines

That wasn’t a problem here, because the organizers had already agreed that each team of four trained monkeys would produce a finished 18X24 painting in an hour. The only way for this to work was for us to focus on our established goal in the fifteen minutes we were allotted. Call that ‘achieving milestones,’ if you must. In the real world, a deadline is a great way to avoid overworking.

Respect each other’s work

In other versions of this game, I’ve been frustrated when subsequent artists spent their fifteen minutes redoing earlier ideas instead of refining them. Some revision is necessary, because in the heat of the moment, one doesn’t always do it right. But wholesale reworking of another’s ideas is terribly disrespectful, not to mention a waste of time.

Document the process

Whoops, I didn’t do that. Wish I had.

Celebrate achievements

For us this just involved a lot of whooping and hollering, but more measured recognition is necessary in every real collaboration. We recognized each other as hardworking peers, so there was no buried conflict to be exposed. There’s nothing like one artist with a towering ego to sour a collaboration.

Resolve conflicts amicably

We didn’t have any conflicts, but if we had, we’d have just talked them out on the spot. It’s possible for people to become terribly ego-invested in a cooperative project, with one or more people secretly believing they’re the driving force and their partners are just useful idiots. Nip that thinking in the bud.

Promote the heck out of your collaboration.

That’s what I’m doing right here, folks! (The painting is already sold, but there’s always next year.)

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.