“I was wondering if you can address the different types, weights and rag content of watercolor paper and what they’re best for,” a student asked. Sure, although I obviously can’t talk about every paper on the market.

There are three general types of watercolor paper. (There’s also a plastic product called Yupo, which is non-absorbent so acts entirely differently than paper. It’s a gas to use.)

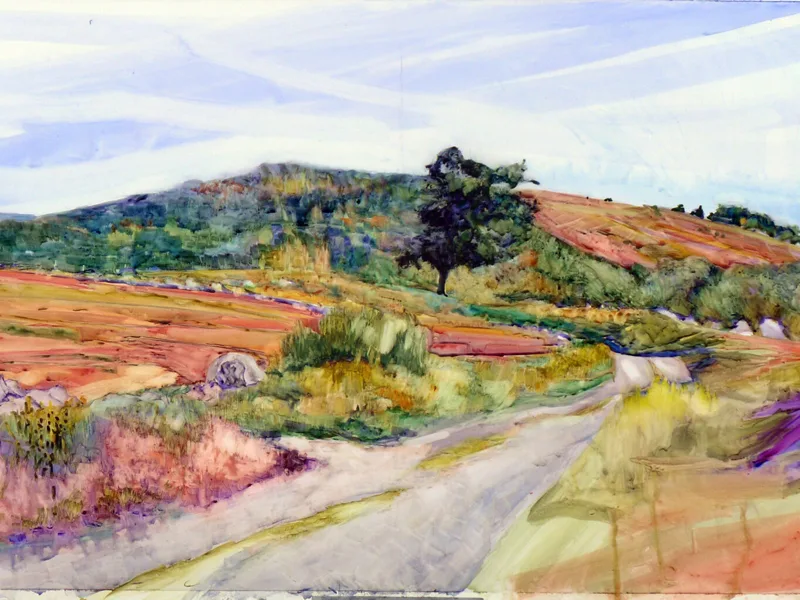

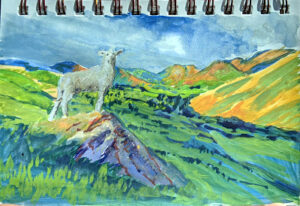

Cold Press has a moderately-textured surface. This is the most popular paper used today because it’s highly absorbent, allows for some detail, but also allows for broken washes and scumbling.

Rough is a deeply-textured surface. It is the most absorbent paper. It’s great for broken washes and scumbling, but you can’t get much detail on it.

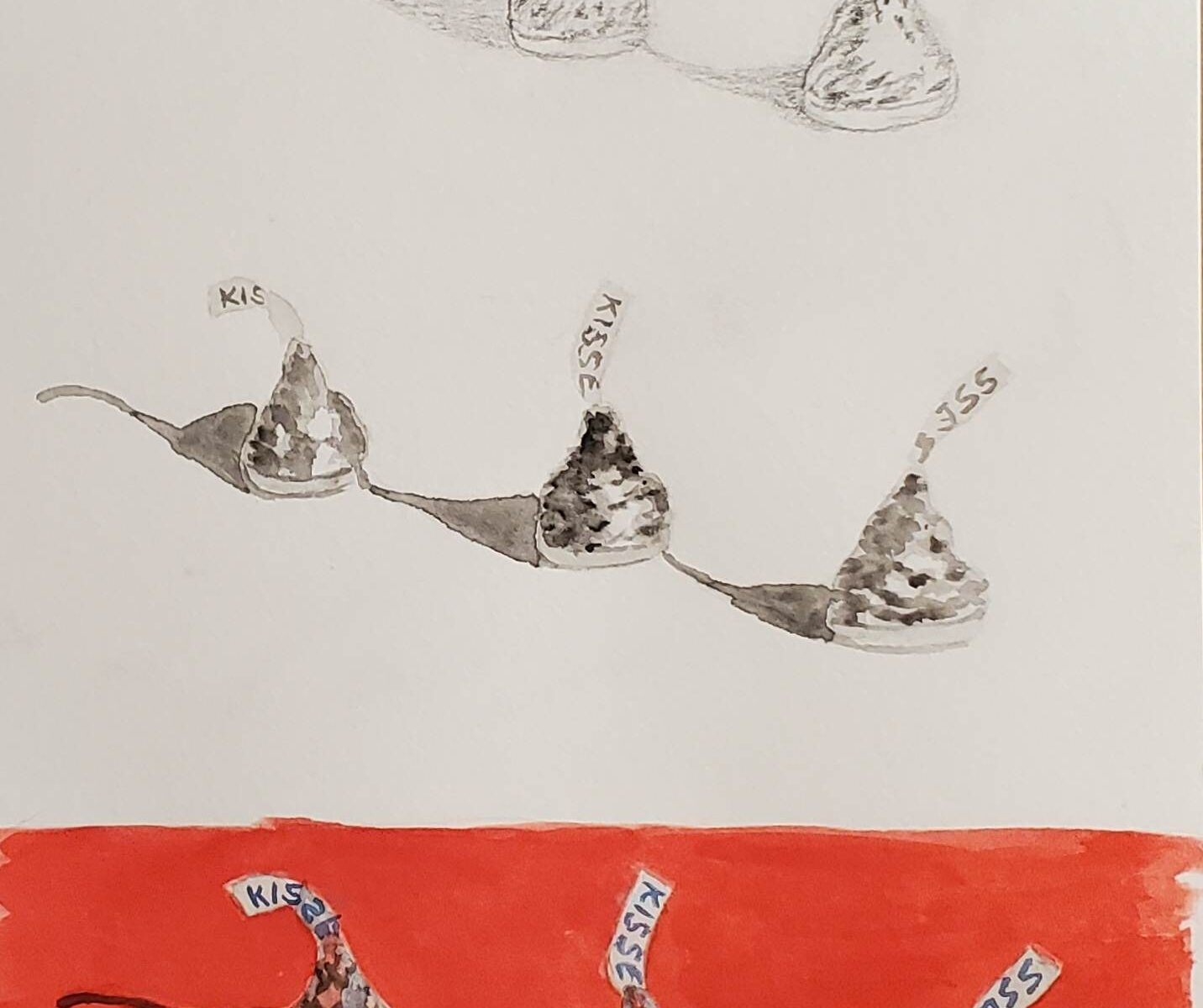

Hot Press or Bristol has a smooth surface. It comes in several surfaces, ranging from plate (highly polished) to vellum. It’s exceptional for detail work, making it a favorite of illustrators. The least absorbent of the papers, it’s also the easiest to lift color from. (I carry this Strathmore Bristol notebook with me at all times because it’s good for pencil, ink and watercolor.)

What is sizing?

All watercolor papers have sizing added to keep the paint on the surface. Sizing may be gelatin (traditional) or a synthetic product. Sizing stops paint from sinking and spreading into the paper. Without it, paper is just a big, uncontrollable sponge.

How important is 100% rag or cotton?

Rag means papers made with cotton textile remnants, which have a longer fiber than cotton linters. However, with so many synthetic fibers in modern textiles, the cotton rag supply is dwindling. Cotton linters (byproducts of cotton processing) are now either the chief or only fiber in 100% cotton paper.

Cotton paper is superior in strength and durability to wood pulp-based paper. It won’t yellow as quickly (although the sizing can also cause yellowing), as it doesn’t contain the high concentrations of acids that are in wood pulp. However, many non-rag watercolor papers are now acid-free as well.

Cotton fiber is more absorbent than wood pulp. Because the fibers are longer, it tolerates more lifting and scrubbing than wood pulp.

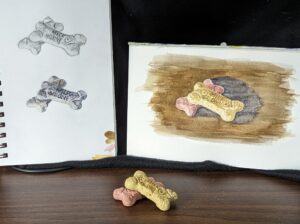

There are places where fiber content doesn’t matter. For quick color studies, grisailles, and other transient works I use Strathmore 400, which is a moderate paper. To get 100% cotton, I’d need to step up to Strathmore 500.

How can I tell if a paper is 100% cotton?

If it’s not labeled 100% cotton, you can assume it isn’t. Some common cotton papers are Fabriano Artistico, Arches, Stonehenge, Winsor & Newton, and Hahnemühle, although of course there are many others, including the aforementioned Strathmore 500.

Weight

Watercolor papers come in three weight classes:

· Light – 90 lb.

· Medium – 140 lb.

· Heavy – 300 lb.

For comparison, copy paper is 24 lb.

90 lb. watercolor paper requires stretching and/or careful taping or clipping. In general, most painters use 140 lb., which doesn’t buckle except if totally saturated. 300 lb. paper is for working very wet/very large.

Format

Watercolor paper comes in several formats:

Blocks are glued on all four sides. The finished painting is removed by slitting the glue with a knife when dry. Because they’re stabilized, they can take quite a bit of water without buckling. They also obviate the need for a separate support board.

Pads: Although not as stable as blocks, most pads work well enough with a single binder clip and a support board. They’re generally less expensive.

Loose sheets: These need to be taped or clipped down with binder clips, but give size flexibility and cost less than blocks.

Rolls: The most cost-effective way to buy watercolor paper, this is also the only way to make very large watercolor paintings.

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.