Cheap materials or weird deviations from process inevitably lead to disastrous results, but artists keep doing it.

|

|

Untitled (Floral), 1960, Morris Louis, showing deterioration of untreated cotton duck ground, courtesy the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (it’s since been restored). |

This week, I’m assembling materials for my watercolor workshops aboard schooner American Eagle. I’m giving them QOR watercolors by Golden. These are professional-quality paints, not student-grade—even though some of my students will have never painted before. I want to create impassioned painters, and bad materials are the best way to nip creativity in the bud.

Cheap materials are only part of the problem. There’s a mistaken association between ephemeral materials and ‘authenticity’ that arose in the latter part of the 20th century. It echoes today, and drives artists to experiment with painting on cardboard, collaging paper with oil paints and other unstable methods.

|

|

Misty Moonlight, c. 1885, Albert Pinkham Ryder, courtesy Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art |

“I was beginning to wonder if it was just the art historian in me, but I see people using such unbelievable crap in their artwork and it makes me shake my head,” a reader wrote.

There are vogues that sometimes result in spurious results. Oiling out is a traditional technique where a hint of linseed oil is applied to a dried layer to make the next layer appear to sink into it. A variation appeared about a decade ago. Painters would paint into a soup of wet medium. It was supposedly okay because the medium was fast-drying alkyd, and it allowed mediocre painters to produce something that looked like Tonalism.

|

|

Moonlight, c. late 1880s–1890s, Ralph Albert Blakelock, courtesy Phillips Collection |

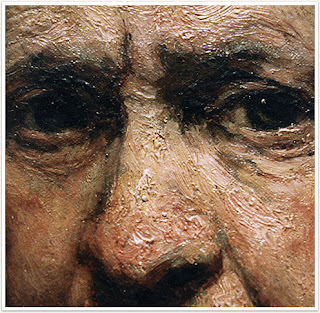

I was immediately reminded of the sad fate of Ralph Blakelock’s paintings. He was a Tonalist, also interested in luminosity. He tinkered with his paint application in search of new effects. Unfortunately, many of his canvases are badly deteriorated because of it.

Another painter whose work has rotted out because of bad technique is Albert Pinkham Ryder. Ryder built up his paintings with layers of paint, resin, and varnish applied haphazardly on top of each other. He painted into wet varnish and disregarded the different dry times of his pigments. He experimented with candle wax, bitumen and novel oils. That gave his paintings the luminosity that he was aiming for, but at a price.

Paintings by Ryder are consistent only in their instability. They’ve darkened seriously over time and developed terrible cracks and crazing. In some cases, they’ve never fully dried or have completely disintegrated.

There are only a few oils with natural drying properties. These are linseed, tung, poppy seed and walnut oil. Non-drying oils like almond or olive oil are never suitable for oil painting

Similarly dubious is the process of starting a painting in acrylics and then finishing it with oils. It’s unnecessary once the painter masters the process of wet-on-wet painting, and it has no long history proving it to be archivally sound. We know that the reverse (acrylic over oil) delaminates almost immediately. That means the layers do not bond.

I learned to paint back in the 1970s with a homemade medium comprised of turpentine, Damar varnish, linseed oil and a drop of cobalt drier. It was fairly standard for the time. I used it until I spent a day wandering around the Albright-Knox Art Gallery looking at the terrible cracks and crazes in Clyfford Stillpaintings. The 20th century masters are not paradigms of painting technique; many of their paintings are now in terrible shape. Zinc oxide grounds were much in vogue at the time, and the heavier cadmium pigments are pulling away from them now.

Companies like Grumbacherand Gamblin hire chemists to make and test materials. I trust them far more than I trust my own judgment in chemistry.

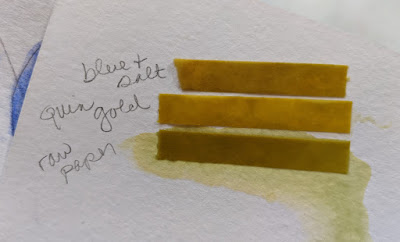

Bad grounds are a chronic problem for conservators. “Morris Louis did wonderful color work on unprimed canvas,” my reader noted. “Museums tear their hair out.” Yes, a good ground can be expensive, but it will extend the life of your paintings—and make the painting itself easier. If you insist on painting on cardboard, make sure you insulate it from your paint with an acrylic or PVA sealant.

Oil painting is 1400 years old. There’s not much that hasn’t been tried in that time, and the standard protocol we use today is the result of that trial-and-error. Cheap materials and weird deviations inevitably lead to disastrous results, but artists keep doing it. That’s a misdirection of creativity.