Painting horrible watercolors isn’t just my special skill; it’s something anyone can do!

|

| A lot of artists don’t like Winsor & Newton field kits, but they’re still my go-to for extreme backwoods drawing and painting. |

Don’t test your colors

Beginning watercolorists usually put down washed-out, delicate colors. These have too much water in the mix. Or, they’ll use too little water, and their unloaded brush will scumble instead of flow. Sometimes they’ll miss the proper color entirely and spend the rest of the painting trying to fix their bad mix.

The answer is to make informal swatches on a scrap piece of paper. Just make sure you use the same paper and brush you plan to use for the final assault.

Pay attention to where excess water might be entering your process. Are you unconsciously washing your brush after every stroke, or not mixing enough paint and trying to stretch it out?

Fiddling

Putting layers and layers of light color down makes great mud. So does putting paint down and then endlessly fussing with it. See above, make the proper color, and lay it down in a few strong strokes.

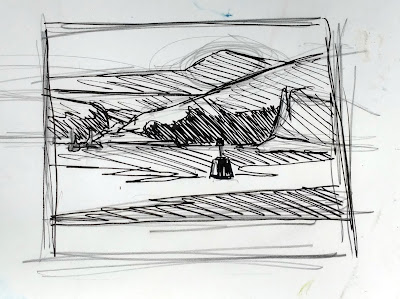

|

| Do a value study, unless your watercolor is a value study. Then do it anyway. |

Too small a brush

Small brushes give you less control, not more. They’re harder to hold still and they run out of paint just when you need it most. Worse, artists get diddly with them. Practice with larger brushes and a lighter hand.

|

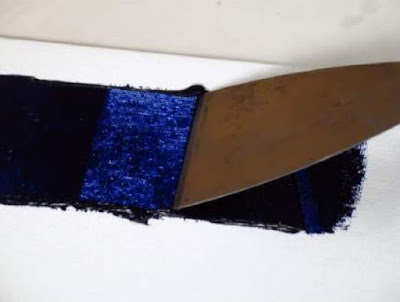

| Bloom is almost unavoidable when painting off the deck of an ocean-going boat, but it’s still annoying. |

Bloom

More properly known as backflow, this happens because the paper is still wet, even though the surface looks dry. Bloom can be used as a watercolor effect, but it more typically happens because the artist isn’t patient, or because environmental conditions are such that your paper will never dry. Or, in my case, because I’ve spattered water all over everything.

Use bad materials

Good watercolor paper contains sizing to keep paint from sinking into the paper. That allows colors to sparkle, and stops the paper from buckling. Cheap papers aren’t properly sized.

Brushes are more important in watercolor than they are in oils. It’s not necessary to have only expensive brushes, however; my go-to rounds are

Princeton Neptunes.

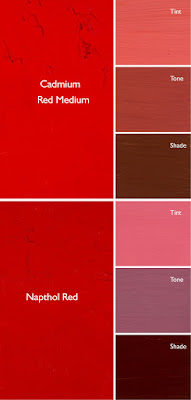

As in all painting, cheap paints are a false economy. Better paints contain more pigment.

|

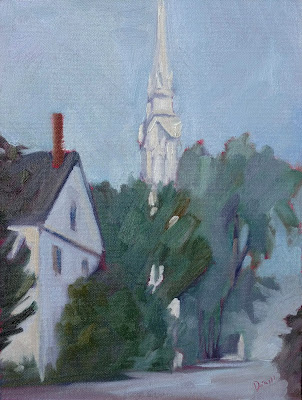

| Watercolor can capture the passing scene better than any other medium. This was painted off the deck of American Eagle. The speckling in the sky was caused by salt spray. What a life! |

Don’t bother with a preparatory value sketch

Value sketches are critically important in all media, but especially in watercolor. You should start with a plan, and your plain is laid out in lights and darks.

Unlike oils and pastels, you have few options to correct a bad drawing once you start it. It behooves you to work out all the kinks before you lift a brush.

Don’t mix your colors in advance

Time is a critical factor in watercolor, and if you have to stop and mix in the middle of a passage, you’re going to make a muddy, blotchy mess. Instead, mix the colors you think you need for that step and test them on your scrap paper.

|

| Let your paper breathe! |

Don’t leave white space

Watercolor is all about paper showing through, so why not let that happen?

Use all the colors

Watercolorists tend to carry far more pigments than oil painters. Want to keep it fresh? Pare down your palette and keep mixes down to three or fewer pigments per pass. And avoid hues and convenience mixes; they’re already mixtures and will further muddy the waters.

Get fussy, fast

Start by thinking out the big shapes first. Too much detail too fast throws the volume relationships off in a painting or drawing.

Watercolorists who fixate on detail at the beginning tend to delineate everything, everywhere. They haven’t given their minds time to sort out what’s important. Detail belongs in the focal point(s) of a painting.