I hate to see people waste money on a cheap pochade box that won’t work.

|

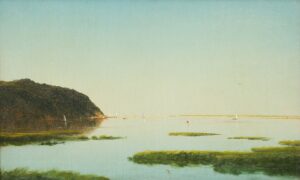

| My current system is an Open M box on a carbon-fiber tripod. It’s lightweight and puts up with a lot of abuse. |

Last week I discussed how Google drove me toward inexpensive and fatally-flawed Meeden pochade boxes. I do not generally tell people what boxes to buy, as there’s a tremendous range of excellent options. But I don’t want to see students waste money on a cheap box that won’t work.

We’re a month out from the start of plein air season here in the northeast, so it’s time to research and order a box if you need one. Some manufacturers are on their seasonal hiatus, but if they make the box you want, it’s worth waiting for.

|

| My super-light pochade box when it was new (and clean). |

Unfortunately, most pochade boxes are sold on the internet, so you can’t twiddle the dials in person. You must rely on word-of-mouth. The good news is that there are some excellent products out there.

Many people have been given some version of a French box easel by loving friends or relatives. If you’ve got one, by all means use it, but don’t voluntarily inflict one on yourself. They’re heavy, difficult to set up, and you can’t slide the paint out and store it in the freezer. Pochade boxes are lighter and nimbler.

If money is an issue, make your own. I have instructions here for making a lightweight aluminum box. This was my primary box for several years and I still use it for backpacking, as it’s the lightest box I own.

|

| Jennifer Johnson’s variation on that theme. |

My student Jennifer Johnson decided to make a box like mine, but her husband ordered the wrong binder. It was a fortuitous accident, because her box is smaller and stronger. It pairs up perfectly with her Mabef M-27 field easel without any drilling or special machining. She’s used two of them—one for acrylics, one for oils—for four years now without any problems.

Or, you can use Victoria Brzustowicz’ ingenious, cheap and simple solution. She hinged two aluminum baking sheets from the Dollar Store together with a strip of duct tape. Open, it’s a paint box; closed, it goes in a plastic bag in the freezer. She also uses it with a Mabef field easel.

|

| Victoria Brustowicz’ variation on the theme cost her all of $2. |

That Mabef field easel can also be used with a plastic Masterson sta-wet palette box and disposable palette paper for another lightweight and inexpensive combination.

In all cases, you’ll have to tinker with bungee cords and clamps to secure the box to the easel, but it does work.

A few of my students have the Leder easel. At $119 (not including the tripod), it’s reasonably priced, stable, and extremely compact. You must buy your own tripod and paint box, but that, again, means you can use a sta-wet palette box. It’s also a useful system for pastels, because it allows you to use your existing pastel box.

|

| New Wave u go pochade box belonging to Ann Clowe. |

I’ve also seen several New Wave u.go pochade boxes over the past year. They’re birch and use magnets instead of clasps. They seem solidly built and have a lift-out palette.

My current everyday box is an Easy L box by Artwork Essentials. (I also use their umbrella, because it stays where I put it.) The box is durable, basic, and you can set it up so it hangs with the palette at the same angle as your canvas. That’s useful for demoing but I never do it in real life.

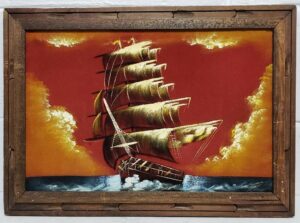

Another lovely box in a similar style is Open M’s panel/palette holder. It’s also well made of Baltic birch. The major difference is in the style of hardware.

|

| Terrie Perrine using the Leder system with her own pastel box. |

Guerrilla Painteris a well-known brand of extremely-robust pochade boxes. I have a 12X16 Guerrilla box that is so tough I could drive over it with my truck and then use it. That comes at a price, however; the box is too darn heavy for anything other than park-and-paint plein air.

Strada makes the only aluminum pochade boxes that I know of. That’s a pity, because aluminum is stronger and less prone to moisture damage than wood. It doesn’t result in much weight savings, however; the 11X12 Strada box weighs only an ounce less than the 10X12 Open M box.

En Plein Air Pro now has a system for oil and acrylic painters with a greyscale mixing tray. They also have a portable pastel easel. I worked briefly with the oil-palette at my Sedona workshoplast month, and it seemed quite solid and practical. I have had one of their tripod trays for years, however. It’s rigid and durable.

All opinions on these products are my own. A handful of them use affiliate links; if you click and make a purchase, I may receive a commission.