|

| Workspace or spiritual battleground? |

This weekend I spoke with a former student who is now in his fourth semester at Rhode Island School of Design. Inevitably, we discussed criticism. He made a point I’ve heard from other students: all art school criticism is fundamentally self-referential. What matters isn’t the technique, intellectual rigor or theory brought into the process, but how the work relates back to the artist.

This circular thinking came back to me forcefully this morning. For the past few weeks, our pastor (Tony Martorana at

Joy Community Church) has been talking about spiritual rejuvenation. I was struck by how much modern art needs that. Truly, a valueless, concept-free, rudderless visual art world is nothing more than those dry bones Ezekiel so powerfully and movingly described.

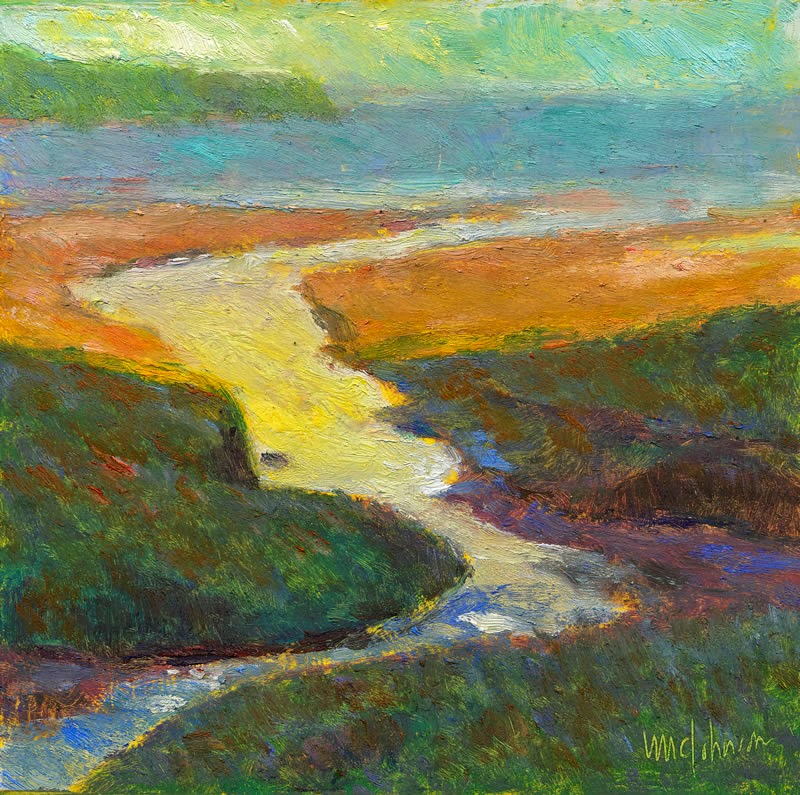

But that’s still abstract; I wrote last week that I don’t see myself having the moral intelligence to paint the cardinal virtues. Pastor Tony used an agrarian metaphor to describe spiritual rejuvenation, to which I can easily relate. And I don’t mean to denigrate the spiritual significance of his instruction, but I can see in it a path to better work as an artist.

|

| Rocks are annoying except in viniculture, where they end up being an important part of good wine. (But there’s such a thing as torturing a metaphor.) |

The following are his bullet points:

1.

Remove the rocks. In the northeast, our fields are planted on former forests, where acidic soil caused rocks to rise to the surface. So our fields are surrounded by dry stone walls made of rocks painstakingly removed by our ancestors.

Rocks make soil hard to till and block moisture and root growth. They are not living things; they never were living things. We all have metaphorical rocks in the landscape of our painting technique. These are the internal voices that say things like, “I can’t,” “I’m a second-rate talent,” “I don’t have an MBA,” as well as the bad work habits and distractions that come from a life of working alone.

2. Remove the stumps. These are things which once lived and which might have produced good fruit, but do so no longer. In my life, these are primarily the lessons of the dead, which were perhaps well-meant and instructive when I was fifteen but which tend to hobble me today. (That isn’t meant to denigrate the importance of those people, for in the not-too-distant future I may be a stump to that kid now at RISD.)

|

| Then there’s pruning. |

3. Remove the weeds. In early spring, everything is covered with a green loveliness, and it’s frankly hard to tell the useful plants from the bad. Then overnight your garden is overrun with bindweed and dandelions are blowing across the lawn. I often have a hard time distinguishing between good and bad ideas, because often the bad ones are frankly more seductive. In the garden, I use my intellect and experience to determine which plants are weeds, and I pull them before they set roots. I ought to be able to do the same with my bad ideas.

4. Plant a sufficient harvest. There are many factors which limit the harvest, but it can never be greater than that ordained by what we’ve planted. If you never work, you can’t expect to create very much of a body of work, can you? If you work sporadically, or half-heartedly, what do you expect to pull out at the harvest time? If you plant weeds, can you expect to harvest fruit?

5. Then wait. You’re not going to harvest a crop overnight. In fact, in the world of art it is very possible that we may not live to see our harvest at all. But that doesn’t mean the harvest won’t be there.

(All the bullet points are Pastor Tony Martorana’s and were given by him as points of spiritual growth. This specific exposition and application to painting is my responsibility and I don’t mean to misquote him or twist his initial message.)