Thinking about competitive plein air painting? Here’s a useful tool.

|

| Beach Erosion, 8X10, oil on canvasboard, $652 framed, available through Ocean Park Association. |

I met Chrissy Pahucki at a plein air event. She was standing in line with one of her children waiting to have her canvases stamped. Chrissy’s branding came naturally—she always had a kid trailing along. I once asked a show organizer how many years we’d been doing his event. “You can tell how long it’s been by how much Ben has shot up in height,” he answered.

All three Pahucki kids are grown now and Chrissy’s still doing the plein air circuit. In her spare time, she’s a full-time, award-winning middle school art teacher in Goshen, NY. About a decade ago, she created a website to direct-sell paintings called the Plein Air Store, and she still maintains it.

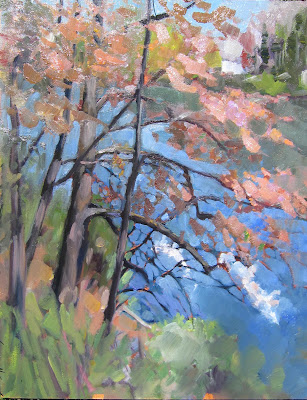

|

| Quebec Brook, 12X16, oil on canvasboard, $1449 framed. |

She also made this spreadsheet for applying to events. It’s a useful tool because it lays out application, notification and event dates in tabular form. That means a busy person doesn’t have to hunt through reams of material looking for a show. Unlike a magazine, it’s searchable. And it’s free. Thank you, Chrissy.

The plein air circuit is where I first met Mary Byrom, Bobbi Heath, Poppy Balser, and many other talented, hard-working and like-minded women. Like Chrissy, they’ve become valued friends. These events are much like the rodeo circuit; the same artists show up at them over and over. Artists compete with each other for prizes and sales, but at the same time, they’re supportive and friendly. That’s a good life lesson right there.

Plein air events teach you to search out beauty. There is something otherworldly about grey, soaking weather that you don’t realize if you only go out when it’s fine. The painting Sometimes It Rains, below, was painted during a complete washout at Ocean Park, ME. I tucked myself into the vestibule at the Temple and painted down Royal Street. Ed Buonvecchio set up right behind me and painted me with my little red wagon. Sometimes It Rains turned out to be one of my favorite paintings. Ed’s painting sold, although why anyone would want me on their wall remains a mystery to me.

|

| Fog Bank off Partridge Island, 14X18, oil on canvasboard, $1594 framed. |

Sometimes there’s very little to work with. I once did an event in a coastal resort comprised of boxy modern houses shoved cheek-by-jowl along a strand. We were forced to find something beautiful, and the only way forward was to search shapes for a transformative angle or trick of the light. “You can make a good painting out of anything” is a good painting lesson and an even better life lesson.

Plein air events teach us to finish work. That last bit used to be my undoing. I once perseverated for years over a commission, to the point where it became a standing joke among my students. “Is that thing still there?” they’d ask as they trooped into my studio week after week.

|

| Sometimes It Rains, 9X12, oil on archival canvasboard, $869 framed. |

But plein air events allow for no such noodling. There’s an immutable deadline. You hand in work whether you think its done or not. A buyer or judge loves it for its unrefined energy. The adage that we spend 90% of our time doing 10% of the work is true in painting. It’s also true that we sometimes spend 90% of our time overworking that 10%.

Plein air painting is, simply, the most important art movement of our time. If you’re interested in it, I encourage you to dip your toe into the competitive process. Start with a regional show near you and see how it goes. Chrissy’s table is a good way to start.