The best portrait painters drag us into the emotional space of their sitters.

|

|

Henry VIII at 49, 1540, Hans Holbein the Younger, courtesy Gallerie Nazionali d’arte antica, Palazzo Barberini, Rome |

My students will be painting self-portraits this week. One of them asked me for a masterpiece to copy. Without hesitation, I recommended the Tennessee painter Tom Root.

My pal Eric Jacobsen calls Tom Root “a national treasure.” His Holiday (Rest on the Flight to Egypt) is one of the few paintings that carries the western tradition of religious painting successfully into the modern era. He’s technically superlative and keyed into the contemporary zeitgeist. Since I want my students to paint in the modern idiom, it’s best that she studies a modern painter.

|

|

La Monomane de l’envie (Insane Woman), 1822, Theodore Gericault, courtesy Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon |

The best portrait painters drag us into the emotional space of their sitters. That is why we can look at a Renaissance painting and feel that sudden start of connection. This is an absurdly truncated list that misses many masterpieces, but it’s a start for any student who wants to study portraiture.

Albrecht Dürer’s Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight could be subtitled, “Look at me and my glorious hair.” Dürer chose to present himself with the iconography usually reserved for Christ, but he’s not saying he’s a god. Rather, he’s telling us that all followers of Jesus are imitators of Christ, and that his own talents are God-given.

How very different is the lesson in Bronzino’s Portrait of a Young Man with a Book. Bronzino was a Medici court painter, and his portraits are all assured, stylish and reserved. This haughtiness reflects the rarified atmosphere in which he worked, but he still reveals the underlying vanity of youth in this young scholar whose name is lost to time.

|

|

The Jester Don Diego de Acedo, c. 1644, Diego Velázquez, courtesy Museo del Prado |

Jan van Eyck is known to most of us for the Arnolfini Portrait, truly one of the most beautiful and enigmatic paintings ever made. Its complex iconography, perspective and rare attention to detail are absolutely clear, and yet we have no idea what the painting actually means.

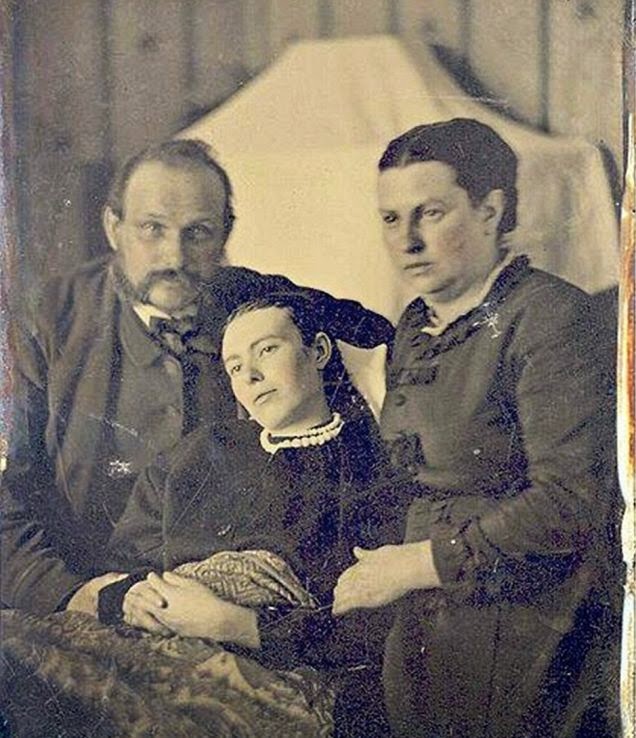

In his day, he was best known for history painting, but the French romantic Theodore Gericault was a sensitive portraitist. He painted a series of ten portraits of the insane, on the encouragement of Dr. Étienne-Jean Georget, a pioneer in psychiatry. His best portraits are the inverse of Bronzino’s—humble, sensitive and honest.

Hans Holbein‘s art is superlatively realistic, and he was able to capture likenesses with rare facility. He had a penetrating understanding of character, and combined technical skill with allusion and symbolism. He must have been a skilled courtier himself, to have survived the intrigues of the English court as well as he did.

|

|

The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882, John Singer Sargent, courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

Sir Anthony van Dyck was a Flemish Baroque artist who became the next great English court painter. He was a favorite of Charles I, and for good reasons: his keen observation, the liveliness of his depictions, and his ability to portray that most elusive of characteristics, majesty.

No list of portrait painters would be complete without Diego Velázquez. Hired to paint popes and princes, his affinity was to the court dwarves and jesters who were kept as enslaved human pets. That doesn’t mean he didn’t understand his regal subjects; his portrait of Pope Innocent X is the penetrating gaze of an ambitious and self-satisfied man.

Rembrandt is considered the greatest painter of the Dutch Golden Age. He was prolific in many genres, but particularly as a student of the human face—especially his own, which he used as a map of the human condition. His Self-Portrait with Beret and Turned-Up Collar is a masterly disquisition on the subject of aging. With age comes wisdom—and sagging jowls.

And then there’s John Singer Sargent, whose motto had to be “Give the people what they want.” He captured the incredible wealth of the Gilded Age, but it’s never clear that he likes his models. In many cases, he reduces them to mannikins, but in The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, he makes a poignant statement about the role of women and girls in society. The girls recede into space in order of age, with the eldest (Florence, age 14) almost enveloped in the darkness of the drawing room.