The art of living is more like wrestling than dancing. (Marcus Aurelius)

I’ve been reminded of that a lot this week as I watch a friend struggle with her husband’s end-stage cancer. It makes one keenly aware that life isn’t exactly a picnic.

There is a misunderstanding that Victorian parents were somehow distanced from their children because they lost so darn many of them. 19thcentury literature, with its recurrent cry of loss, tells us otherwise. It was a period of great innovation but death rates did not drop; in fact it was the Dark Ages of child mortality in the western world. Urbanization, industrialization, poverty, war and unsanitary obstetrical practices were ruthless killers of people of all ages, but especially children.

|

| If you were wealthy, you could hire a sculptor to immortalize your late son in marble, as here, in the Blocher Memorial in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo. |

Consumption, or tuberculosis, was the “family attendant” in all too many Victorian households:

I paid a sad call at the Worths where 2 children seem to be at the point of dying, the poor terrible little baby has constant fits & little Madge two years old, who has been ill 12 days with congestion of the lungs. This is the second time I’ve seen them in this illness…we went into next door where we saw poor little Miss Lee evidently very near the end, but sweet and affectionate as ever. (Louisa Baldwin’s diary, 26 April 1870)

|

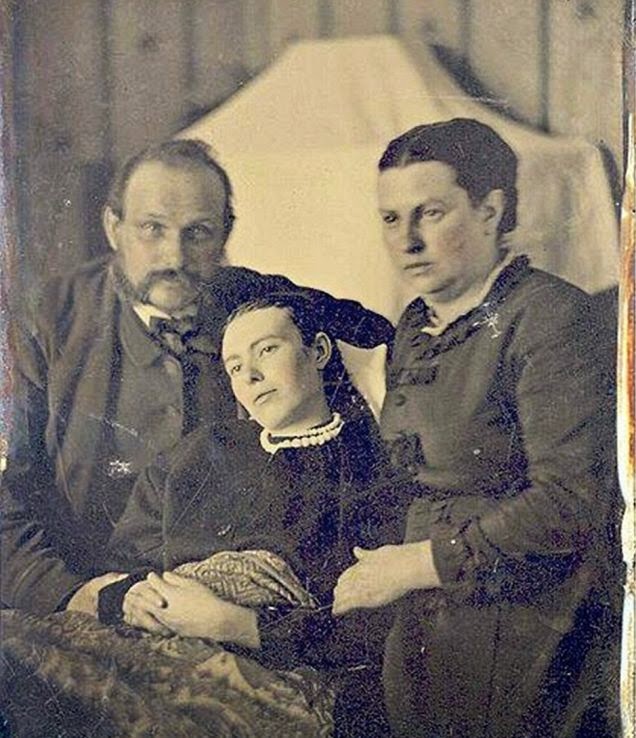

| If you were middle-class, your posthumous family portrait was done in daguerreotype. |

The spread of the daguerreotype photographic process made portraiture more commonplace, but until late in the century most people had never been photographed. This was especially true of children. To the parent who had unsuccessfully nursed a beloved child through a cruel illness, the steady slow erasure of memory was the final blow.

These portraits were not ghoulish memento mori; they were keepsakes to remember specific people. The practice remained in vogue until Rochester’s own George Eastman standardized photography equipment and film, making picture-taking an everyday art form.

Early examples took advantage of the slow exposure of daguerreotypes (and the required stiffness of their posing) to make the subject look lifelike. The deceased was photographed in poses with living family members, braced on furniture, or with a favorite toy.

|

| The family grouping with dead child would probably be the only photo of the kids together. |

There was very little palliative care for the dying Victorian. Most people died in their homes. Yet the idea of assisted suicide or “death with dignity” would have been inconceivable to them. It is a thoroughly modern concept.

I have done one death portrait, of a newborn baby. I don’t have a photo of it since I delivered it hurriedly to the family, but it was (I think) one of the most important things I’ve ever painted. It is rare that artists have the chance to help with healing.