On Tuesday of next week, Lone Pine Real Estate is having its long-awaited grand opening. It’s from 4-7, at 19 Elm St., Camden, ME. You’ll find me there, but not precisely at 4 PM, as I have a prior appointment. There are many forms of creativity, and I’m in awe of the kind of mind that can create a business from nothing. Congratulations, Rachael, Gregg, Nichole, and Ann.

I just moved these three paintings to Lone Pine to replace paintings that have been sold. Two of these are seascape paintings. The ocean and its harbors are my favorite subject. One is a flower painting, and it’s grown on me steadily since I finished it last week.

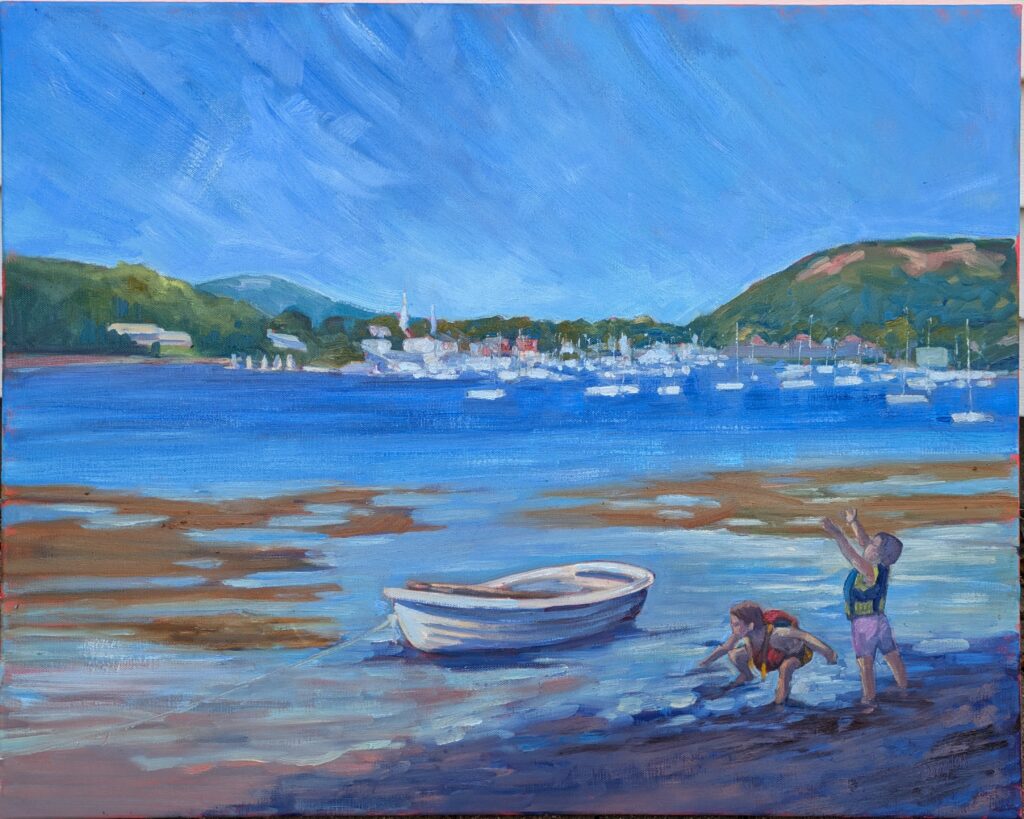

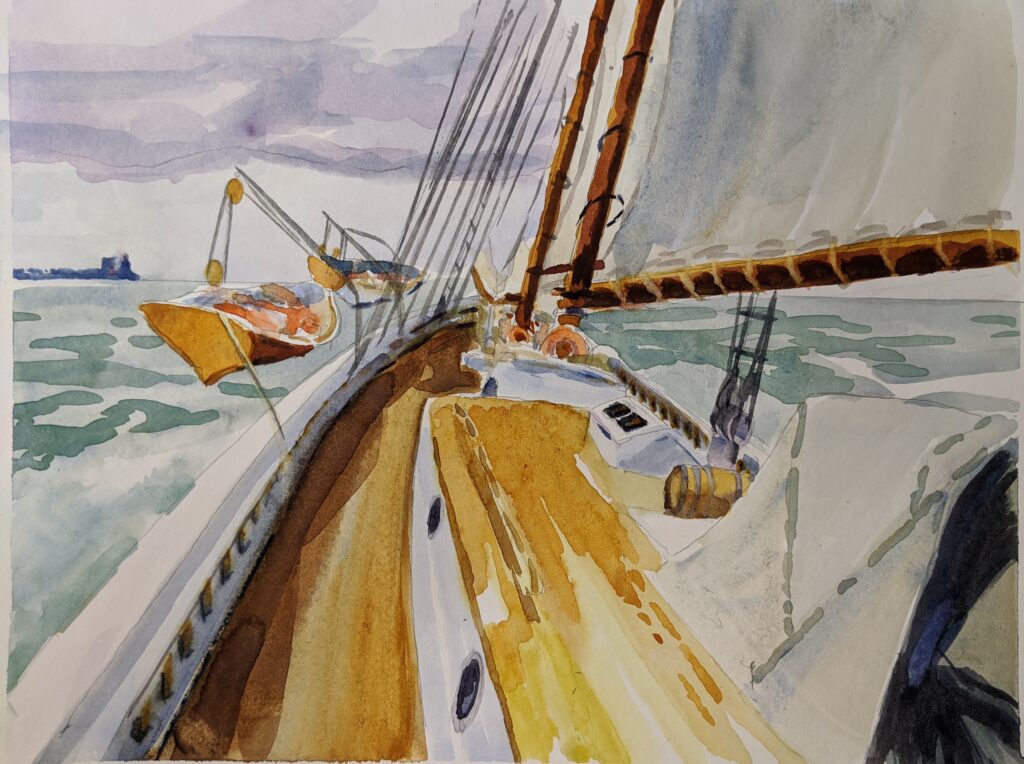

Belfast harbor

Belfast’s most iconic view is the three red tugboats docked at the foot of Main Street. They’re the property of the Penobscot Bay Tractor Tug Company, and they’re not meant to be merely pretty; they’re working tugs that help move cargo around the bay.

Belfast harbor is muscular compared to many other modern coastal towns here in midcoast Maine. Front Street Shipyard is a very large shipbuilder that always has something interesting in its yard; Belfast’s Harbor Walk snakes along the waterfront directly in front of it. It was from this location that I painted the tugs.

My goal was to reduce the tugs and the boat sheds to shapes, rather than paint them in detail.

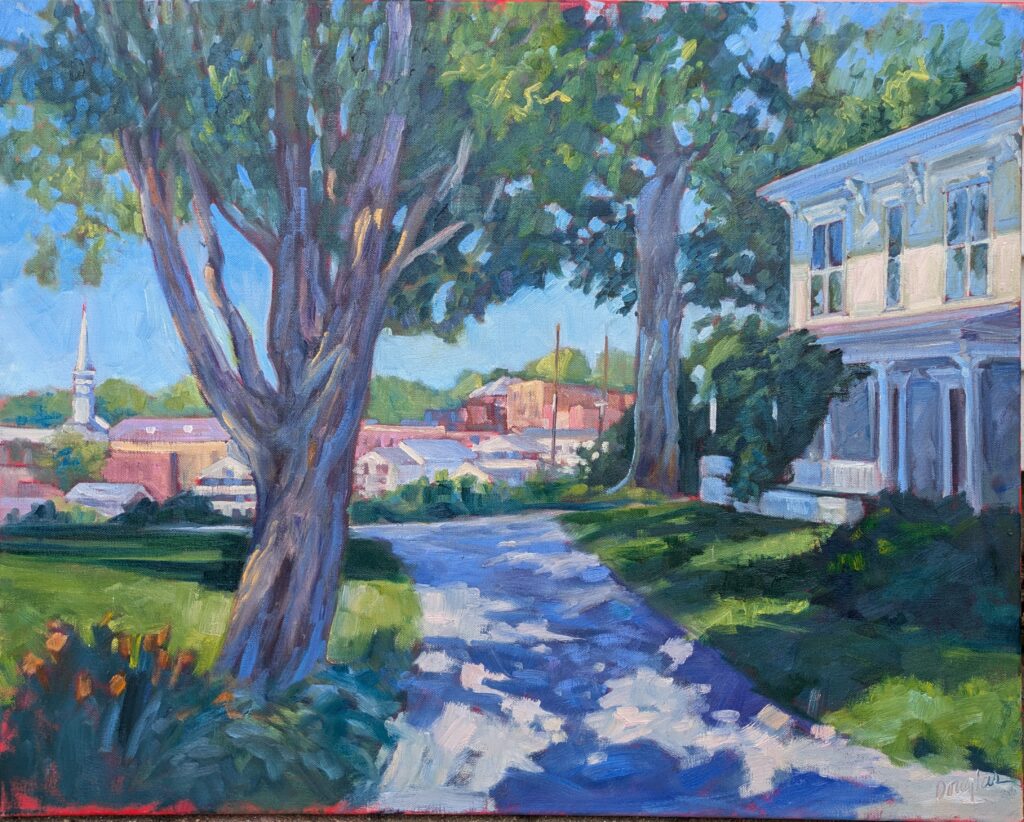

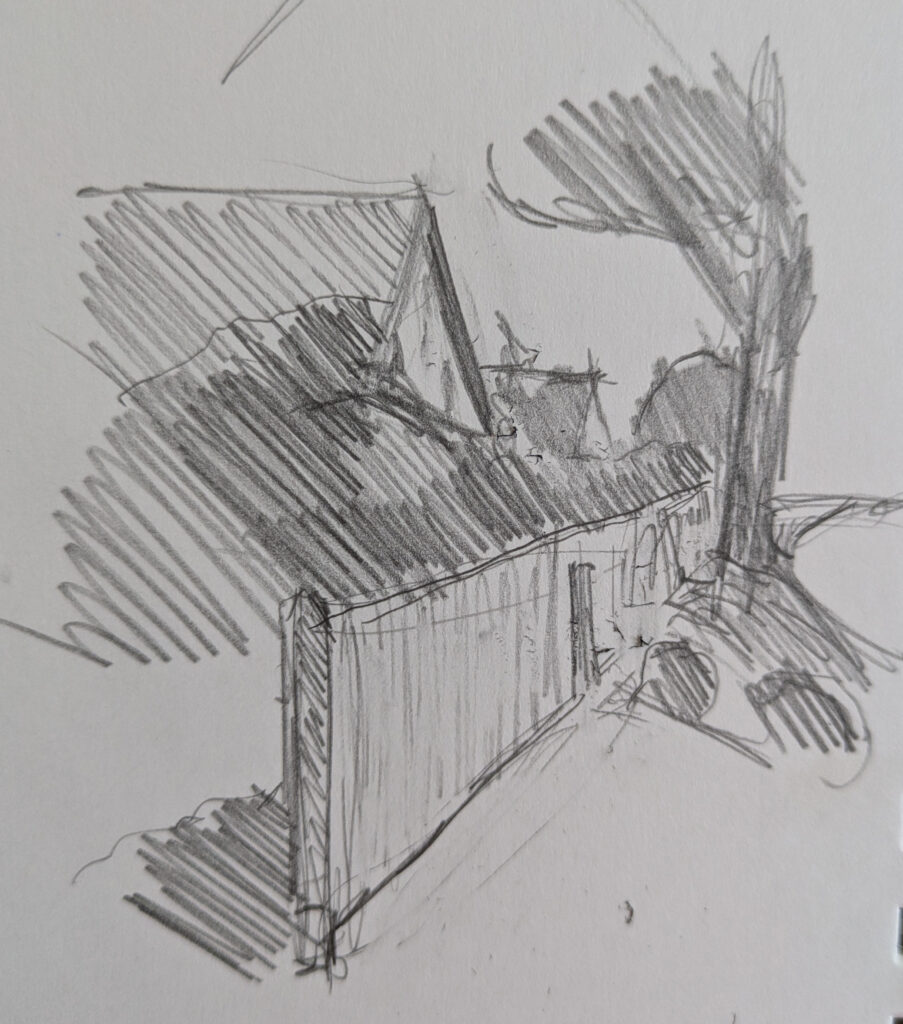

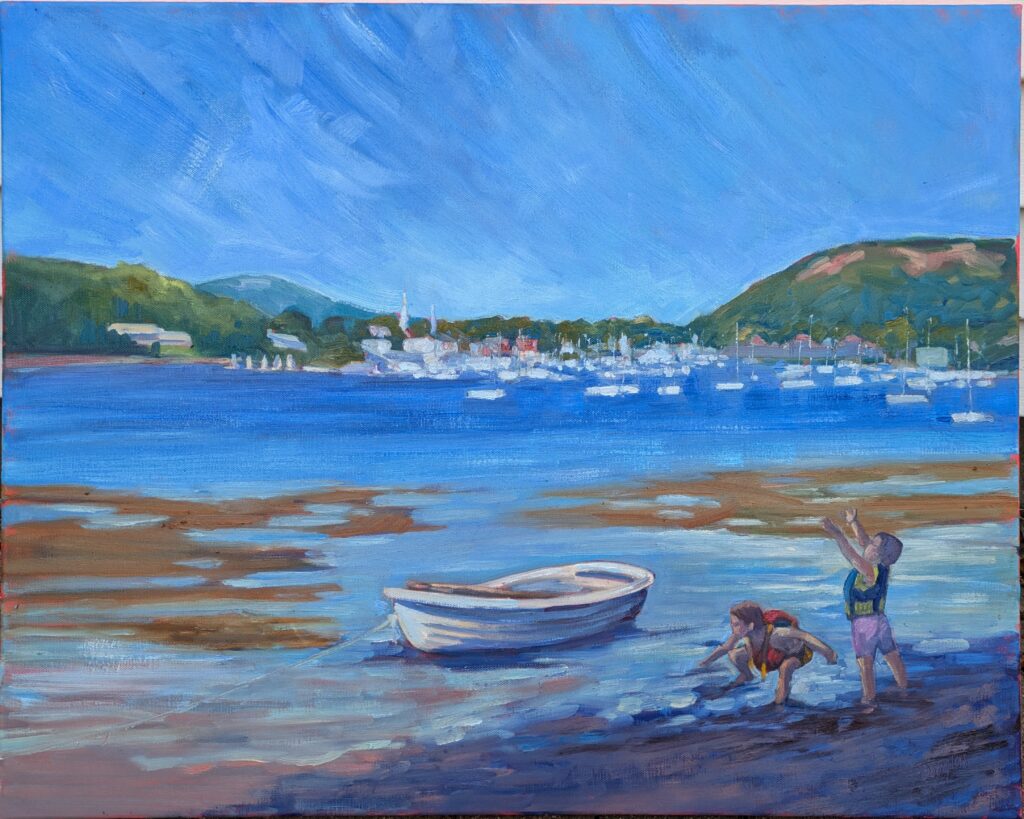

Camden harbor from Curtis Island

I rowed out to Curtis Island in Colin Page’s dinghy to paint Camden harbor. There are often camp kids out on the island beachcombing and I drew the stooping child from life. However, back in my studio I realized that a solitary child just didn’t make sense. I added a second one, which is a self-portrait of me as a child.

I’m blaming this painting on the Words + Pictures Zoom class I just finished teaching. It got me thinking in whimsical terms.

On the return trip, I carefully bungeed my painting to the front thwart. It wasn’t until I was bumping against the dock that I realized I couldn’t reach around my painting to grab the painter. (That’s the line from the bow you use to tie up.) I bumped along merrily in the surf until a nice gentleman grabbed the line for me and helped me unload my gear.

Lace-cap hydrangea and daylilies, Merryspring Nature Center

Merryspring Nature Center is a 66-acre preserve near the Camden-Rockport town line. It has a fantastic daylily garden with varieties I’ve never seen before. I didn’t want to address this planting directly, since it must be fifty feet across and is absolutely horizontal. Instead, I wanted to make it a line of light in the back of an otherwise shady painting.

I don’t paint gardens, as a general rule, but this painting has made me reconsider that.

My 2024 workshops:

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

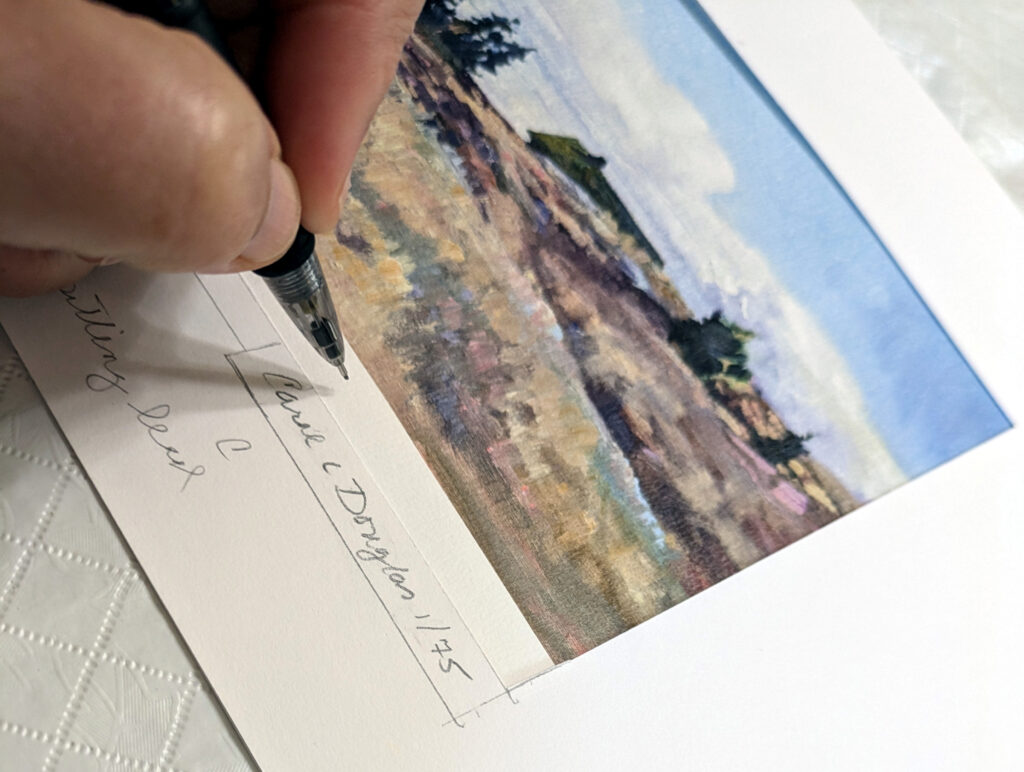

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.