If young women—who should be the most interested in changing this—cling to outmoded and incorrect ideas about the value of women’s art, is there any hope?

|

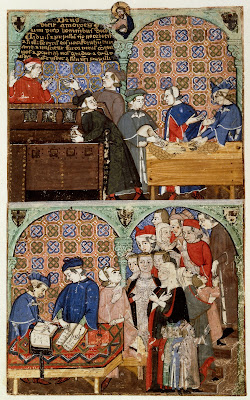

| Pull up your big girl panties, at Rye Arts Center this month. |

I am not going to have the time to write a proper blog. Portland Jetport has been like a morgue for the last few years, but today it’s packed (and therefore slower to clear TSA than normal). America is on the move, and that’s a good thing.

But I’d like to point out a repeated conversation I’ve had this week. It’s been with people of both genders and all ages, but the worrisome part to me is how many young women have told me that it’s not true that you can’t tell men’s and women’s paintings apart. That’s something I mentioned in my talk in Rye, here (scroll down), and in my blog post, here. That was, in some cases, even after they ‘failed’ the test below. They made excuses.

|

| Michelle reading, at Rye Arts Center this month. |

There have been many studies worldwide that document this phenomenon. The most exhaustive was done in 2017. It analyzed 1.5 million auction transactions in 45 countries, and found a 47.6% gender discount in prices. The discount was worst (unsurprisingly) in countries with greater overall gender disparity.

My painting pal Chrissy Pahucki questioned whether it was different for plein air painters, so she ran a test among her middle school students. I shared the test with my adult students, and, last I heard, the guesses were in the same range as random chance—around 51.95% correct guesses.

|

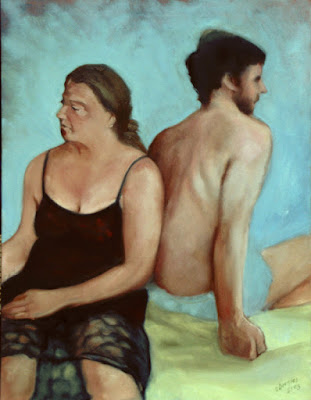

| Saran Wrap Cynic, at Rye Arts Center this month. |

I can’t take it because I can identify too much of the work, but perhaps you can. Try to avoid looking at the signatures if you can see them.

Here’s the link. I’m curious if a bigger sample will show a different result, but I doubt it.

As for what I can do to change attitudes about the gender pay disparity in painting, I’m at a loss. If young women—who should be the most interested in changing this—cling to outmoded and incorrect ideas about the value of women’s art, is there any hope?

I’m off to teach my workshop in Sedona and boarding in just a few minutes. I’ll revisit this soon, I promise.