The jaw of a long-dead artist tells us much more than just the pigment she used.

|

|

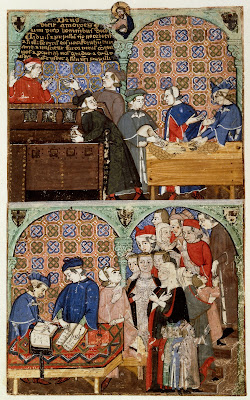

Page from a French Book of Hours, c. 1410-15.

|

Yesterday, several readers sent me this wonderful story of an anonymous medieval religieuse with lapis lazuli (ultramarine pigment) in her dental tartar. Lapis, in the Middle Ages, was as pricey as gold, so its presence in her teeth meant she was a top artisan of her time.

The researchers contacted many scientists, historians, and researchers for help in explaining the mineral’s presence. Some didn’t believe a woman scribe could be skilled enough to be trusted with lapis. “One suggested to [Christina] Warinner that this woman came into contact with ultramarine because she was simply the cleaning lady,” wrote Sarah Zhang in The Atlantic.

|

|

Abbess praying to the Virgin Mary, from The Shaftesbury Psalter, c. 1130-40. The client for this book was a woman. Courtesy of the British Museum

|

We know women were employed as scribes in the Middle Ages, and that convents and monasteries both had a healthy trade in books, sometimes subcontracting to each other. Religious women were as literate as their male counterparts. To history buffs, this discovery hardly overturns our understanding of the medieval economy.

We’re living in a period where women artists are being rediscovered at a rapid pace. But how were they lost in the first place? Consider, for a moment, les trois grandes damesof Impressionism: Mary Cassatt, Marie Bracquemond and Berthe Morisot. They were well-known in their lifetimes; why must they be rediscovered today?

For most of us, living history stops with our grandparents. We assume that life before them was the same or worse. Deep down, we all believe in progress. But in terms of gender relationships, the post-war era was in many ways unique. For example, it’s when women married very young, far younger than their 1890s counterparts. Progress slides along, but fitfully.

What do we think we know about the Middle Ages? To misquote Thomas Hobbes: “no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

|

|

Nuns processing to Mass, fromCollection of moral tracts, c 1290, Courtesy of the British Museum

|

Instead, we see the jaw of a woman who has comfortably reached middle age with perfect teeth, despite her tartar buildup.

Somehow, that speck of pigment on her teeth makes her an individual. “Based on the distribution of the pigment in her mouth, we concluded that the most likely scenario was that she was herself painting with the pigment and licking the end of the brush while painting,” said study co-author Monica Tromp.

“I used to put the (rinsed) water color brush in my mouth to shape it to a point,” one artist wrote to me. It made her feel a sort of kinship with this long-dead artist. The more things change, the more they stay the same.