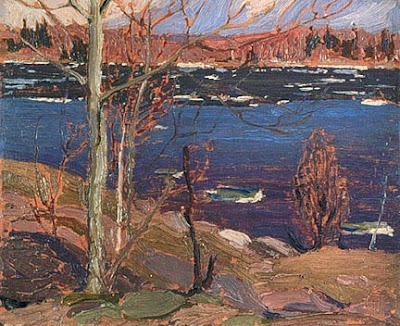

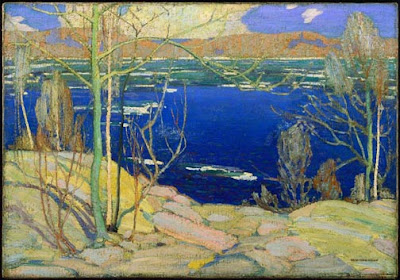

Here are two paintings by Tom Thomson which demonstrate how he went from a field sketch to a finished painting. He changes the aspect ratio a bit but it’s blown up roughly 3.5 times in the final work.

“The Opening of the Rivers: Sketch for ‘Spring Ice’” (1915)

oil on wood-pulp board21.6 x 26.7 cm (8.5X10.5 in)

oil on canvas72 x 102.3 cm (28.3X40.3 in)

Both are owned by the National Gallery of Canada, http://national.gallery.ca/ and displayed on http://cybermuse.gallery.ca/.

I like this way of showing pictures in process. Now I can open multiple tabs or windows with large views of photos from the blog. Sometimes I open them in two windows, as I did with this blog entry, because I want to compare two stages of a painting side by side.

Of course, having done that, I am confused about the sketch. In the blog entry itself, both paintings look ‘finished’ but when I expand the sketch, suddenly I see that it is very abstract and rough when compared to the painting.

Is this the equivalent of all those pages of studies that I have filed away in my “history’ folder? Or would he show the sketch as a finished work?

And what does he get out of the sketch? I see value studies, sometimes changed in the finished picture, and I take your point about refining one’s drawing, but he could not produce the final painting without being in the field or having a photo — or COULD he?

This comment has been removed by the author.

I thank you for your awesome idea about Google docs. It really is seamless and more informative.

I believe the painting was acquired by the National Museum of Canada in the year it was painted (1916) and the sketch was acquired by the National Museum by a bequest of Dr. James MacCallum of Toronto in 1944. Dr. MacCallum was Thomson’s patron.

From that scant information I would deduce that the sketch was primarily done as a model for a finished painting. It would have been quite ordinary for the artist to sell or give the sketch to his patron.

I have no way of knowing whether he did the final picture in the field or studio. Had he used photography he would have been limited to black-and-white and the images from. Kodak’s revolutionary Brownie (1910) weren’t anything like the digital images we routinely paint from today. Thomson spent a lot of time in the wilderness, so it is possible he went back to the same location the following year.

But I think he could have done the final picture in studio directly from this study. It emphasizes graphic design at the expense of immediacy. To see what I mean, look at the main tree. In the sketch, the light patterns on the bark are perfectly observed. On the finished painting, the tree has been beautifully abstracted.

Thomson certainly had the chops to paint the wilderness from memory.

Why is such a field study valuable? The answer lies in the thing plein air painters find so difficult—there is a breathtaking amount of information in even a simple landscape.

Your brain organizes and edits this information in a way cameras can’t. Your field study teaches you to observe, to find spatial relationships, to edit out the superfluous. In the process, you learn the objects so that your next iteration is more finely drawn.