The dark passages in a painting are what anchor it and drive our eyes through it.

|

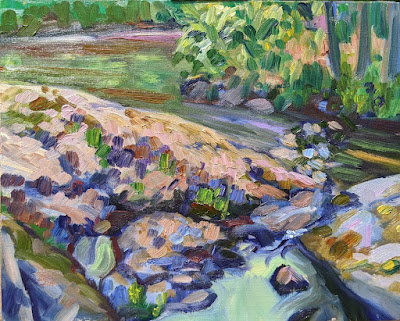

| Bend in Harkness Creek, 10X8, by Carol L. Douglas. |

“A painter should begin every canvas with a wash of black, because all things in nature are dark except where exposed by the light,” Leonardo da Vinci wrote. Well, he would think that way, being a Renaissance man. We haven’t painted with chiaroscurosince art was upended in the 19th century by the Impressionists.

That doesn’t mean light and dark are unimportant. We must still find ways to anchor ourselves in the darkness that defines the light. These “dark” passages may not be literally dark; they may be defined by color temperature, as Claude Monet demonstrated.

|

| It was a very dreary day so I started by amping up the color. |

A ‘passage’ means the same thing in painting as it does in literature: a short excerpt that’s meaningful in itself. There’s an overtone of the word’s roots in this, because an artistic passage often takes us from one place to another. Painting is all about motion on the canvas. When you stop seeing painting as the business of copying objects, and start seeing it as creating passages, you will have advanced from being a student to being a painter.

The dark passages in a painting are what anchor it and drive us through it. I drill my students constantly on the importance of value studies before they pick up their paintbrush, so they know how to make a thumbnail and then either a grisailleunderpainting (oils or acrylics) or a monochrome study (watercolor) before they move to color. But the most common problem among student painters is that they make these value studies and then ignore them.

|

| I had less than two hours to paint this, so by necessity, it was blocked in roughly. |

Watercolor painters—assuming they’ve reserved enough light—can add darks at the end. It’s not quite so easy in oils. Oil painters must periodically check to see that they’ve not obliterated the dark passages. In practice, that means continuously restating the darks.

|

| My diagonal doesn’t follow the creek bed, but the shadow pattern. |

This is particularly true in plein air painting, where the light shifts and the painter can be led astray. There are only two imperfect solutions:

- To work on the painting in a short time-frame over a period of several days;

- To keep your value study right next to your painting on the easel and consult it repeatedly.

For practical reasons, I prefer solution number 2.

Restating the darks just means going over the dark passages to firm them up and regain some of the initial shapes that first attracted you to the subject. Even advanced painters need to restate the darks periodically.

In oils, it’s hard to paint dark over light, which is one reason to restrain ourselves from heaping on too much paint in the beginning. You might need to scrape back to get any kind of power back into your dark passages. Don’t hesitate; scraping is one of the oil painter’s best tools. It often reveals things we’ve completely forgotten.

|

| Almost done, and a neighbor stops to say hello. |

It’s a traditional axiom of oil painting that dark passages should remain translucent, and light passages should get the heft of impasto. Rembrandt’s self-portraits are the archetype of this technique. It’s wonderful when working indirectly, but it’s difficult in alla prima painting. Nor is it necessary.

Consider restating the darks as an opportunity to add color into shadows. A small bit of white in these darks will make them sing if they’re well-mixed, but will be brutally honest if you were just plopping down boring neutrals in the shadows.

The readability of your painting relies on a good pattern of darks and lights. I’m assigning you three paintings to analyze this week. Your job is to sketch out the patterns of darks and lights and tell me how your eye is being driven through them. They are:

Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando, 1870, Edgar Degas

London, Houses of Parliament, the Sun Shining Through the Fog, Claude Monet, 1904.

Winter, Monhegan Island, 1908, Rockwell Kent