At the end of her senior year in high school, my young painting student told me that she wanted to go to college. “But you apply to colleges at the end of your junior year,” I exclaimed. She didn’t know. Somehow, she missed “what everyone knows.”

I watched this play out again this week as my goddaughter’s family sold the restaurant they’ve owned and run for decades. They don’t speak much English, and they have no experience selling real estate. It’s been painful.

Order of operations

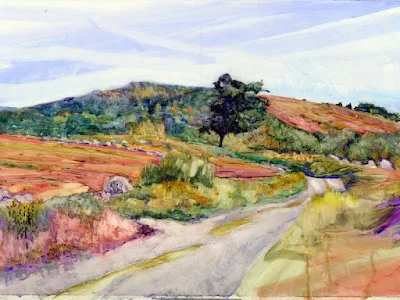

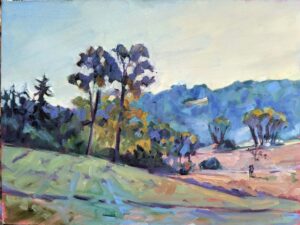

In painting, these “everyone knows” assumptions most often appear in the way paint is applied. There are specific protocols for applying watercolor and oil that have remained unchanged for centuries. Yes, there are exceptions, and people who dabble with other techniques.

Most recently that’s been with alkyd media challenging the ‘fat over lean’ rule in oils. In general, those experiments haven’t gone well. Let the horrible condition of Albert Pinkham Ryder and Ralph Blakelock paintings be a cautionary lesson.

Learning these basic protocols makes painting faster, easier and less fraught, but too many students pick them up by osmosis. That’s why a short course in basic painting technique, such as that taught by my pal Bobbi Heath, is so helpful. The true beginner can’t muck around thinking about more complex questions of composition or color temperature when he can’t even get the paint down on the canvas without making mush.

Our own bad assumptions

It’s hunting season here. I wouldn’t stake my life on a hunter’s judgment, so I advertise my presence by wearing blaze orange when I’m in the woods. (If I’m shot, that hunter is also going to have to explain why he thought a deer was singing “I want a hippopotamus for Christmas.”)

“No one ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American public,” H.L. Mencken may or may not have said. That’s rude, but substitute ‘attention’ for ‘intelligence’ and you get to the nub of the matter. We assume others know all about our art. That’s because we’re all far more important to ourselves than we are to the general public. Most of the time, other people are not thinking about us.

If you want people to see and interact with your ideas, you must model Thomas Edison and constantly, repeatedly, get your stuff out there for them to see. You must wear blaze orange in the public arena.

Most artists shy away from that, but what’s the point of communicating through painting if nobody is looking at what you’ve made?

A reminder

I hope you are cheerfully plugging away with your holiday shopping. Here’s a reminder about my holiday gift guides:

Holiday Gifts for the Budding Artist (including kids)

Holiday Gifts for Serious Artists (including you)

Have yourself a merry little workshop—because selected workshops are on sale this month, and won’t be after January 1.

And, of course, paintings are a wonderful surprise for the special person on your list. Quality original art is one of the few gifts that doesn’t depreciate no matter how much you enjoy it.