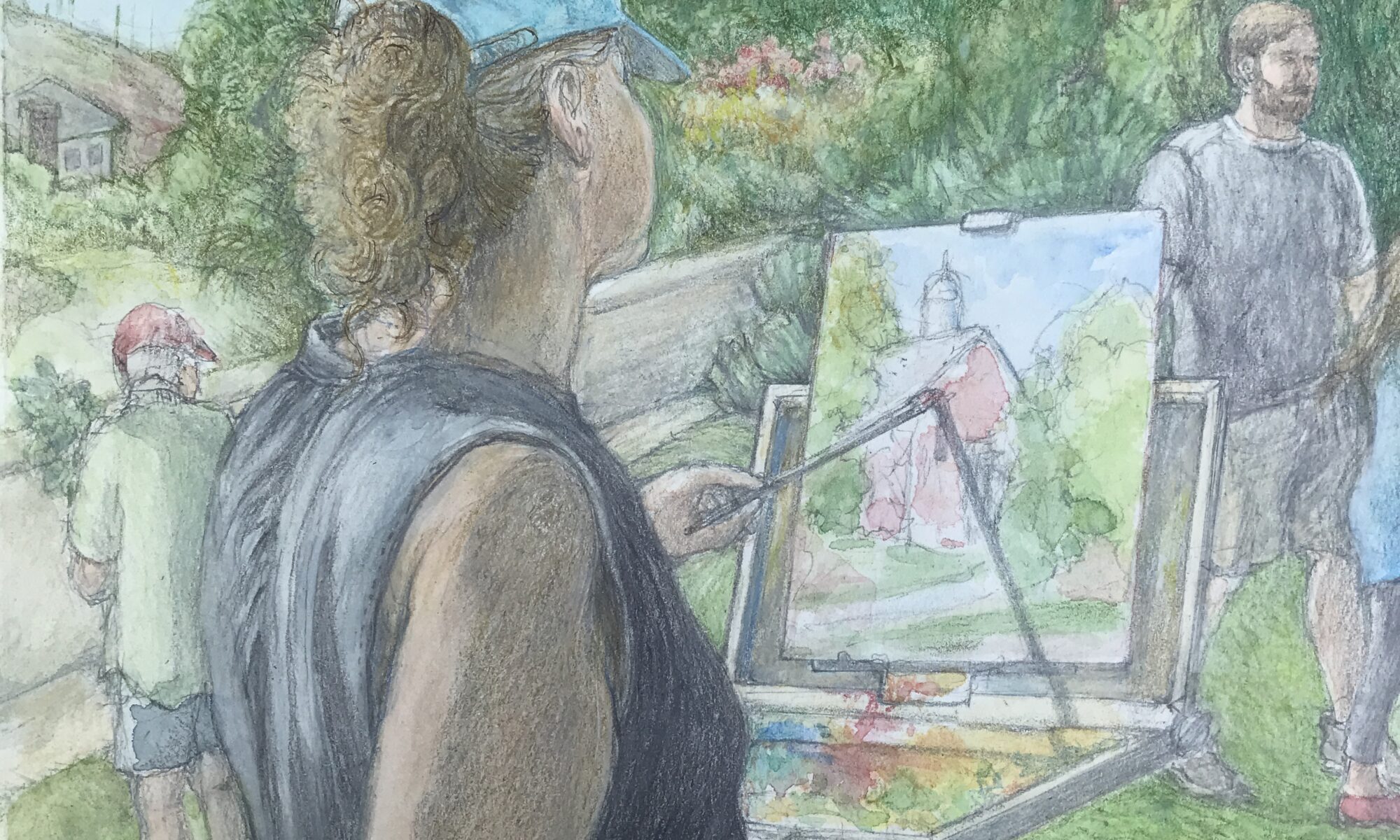

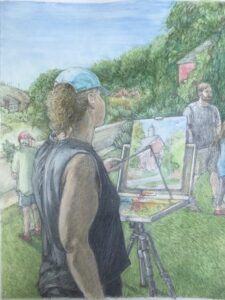

Yesterday, I received the most amazing gift in the mail, from my sometimes-student, Robin Miller. She drew it from a photo she took last summer at the Camden Public Library Native Plant Sale, which was the brainchild of another of my students, Amy Thomsen. My library-supplied assistant at that sale was Becky Bowes, who’s also, coincidentally, another of my painting students.

It’s one of only two paintings (I know of) done of me. The other was by Ed Buonvecchio and is in a private collection in Ocean Park, ME. The owner recently got in touch with me and offered to leave it to me when she sheds this earthly coil. I enthusiastically accepted, although I suspect she’s younger than me.

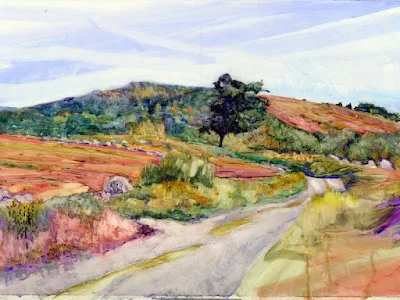

I haven’t been this surprised by a gift since I received the painting, above, of my grandchildren from my buddy Bruce McMillan. In the oddly circular nature of this week, Bruce and his buddy Óskar Thorarensen stopped by my gallery for a brief visit.

On Sunday, I was in Rochester, NY, for Kamillah Ramos‘ wedding. I first had her as a student when she was a junior in high school; she’s now a full-grown architect and last took a workshop with me a year ago. I love the kid, and I cried a little into my lovely embroidered cambric handkerchief. (I’m just kidding; I cadged a tissue from someone.)

Being a serious artist, Kamillah set up an easel so people could paint during her reception. (I went up and adjusted the palette while she wasn’t looking.) Later, I was at the easel with three of my former students as they painted on this most auspicious of days. We all managed to keep the paint off our wedding finery, and that really made me weep with joy.

I am very serious about the business of art, but I also recognize that my work has created a wide circle of cherished friends. There’s Toby Gowing, who mentored me through some very dark times in my life. And Jane Chapin, who saved my nut when we were stranded in Patagonia, and who later captured a street dog for me in New Mexico. And Bobbi Heath, who mentored me into being businesslike. There are my pals from the Hudson Valley, the Adirondacks, Arizona, Texas, and especially Rochester, where I taught for many years. Jennifer Johnson, who pulls me away from the brink every year at my Schoodic workshop. And there are Ken DeWaard, Eric Jacobsen, and Björn Runquist, with whom I paint here in Rockport. I can’t possibly mention you all by name, but I can tell you how blessed I am by having you in my life.

My friend Rita once told me at the start of a party, “you have more friends than you do chairs.” It’s stuck with me all these years, because to me it’s really the greatest blessing life can throw at us. May we all have more friends than we do chairs.

As I said, this week is circular, so it’s fitting that this morning I head back to Camden for the third annual Camden on Canvas, also a benefit for the Camden Public Library. I’ve got my canoe on my car, and providing there are no cock-ups, I plan to paddle out to Curtis Island to paint the lighthouse. I’m reminded of Cassie Sano bounding up Bald Mountain two years ago to watch me paint. If she appears on Curtis Island streaming wet, seaweed in her hair, I promise to give her a lift back to shore.

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.