For decades, I’ve been telling my husband: “When they come to take me away, tell them I never could remember anything.” It’s true; I have a terrible memory for names and dates. I’ve watched a loved one take a digit-span test and shuddered; I couldn’t recite a string of numbers backwards at age 25, let alone now.

Recently I’ve noticed my short-term memory is improving. I’ve attributed that to the infernal modern need for passwords, which we need to unlock everything from our bank accounts to our house.

We take for granted that older people lose cognitive ability – especially memory – over time. But what if that is preventable, or even reversible? That would be tremendous not only for the people involved, but for our aging society.

I’ve got good news for you

Recent research suggests that not only can cognitive loss be delayed, but in some cases even reversed. Researchers had elderly (55+) participants engage in intensive learning for three months in a program designed to mimic the schooling we put our kids through. Not only was there cognitive improvement, it lasted through the one-year follow-up test.

This wasn’t a casual learning program. Study participants took twelve weeks of classes in three subjects about which they had no prior knowledge, choosing from Spanish, photography, iPad operation, drawing, and music composition. They had homework (hah!). That and their attendance were tracked.

Both the six-month and one-year scores were significantly higher than the subjects’ pretest scores. The researchers were careful to note that they’d tried to replicate the environment in which young people learn, so the social bonds created in classes could have been as important as the learning itself.

This wasn’t a lone study, either; they were duplicating the results of earlier research.

A half-hearted approach won’t work

What’s equally important is what doesn’t promote cognitive improvement. Just listening to classical music doesn’t cut it-you must pick up that cello and try to master it. There’s no duffing it to mental acuity. You must focus, intently, on a new skill for it to make a difference.

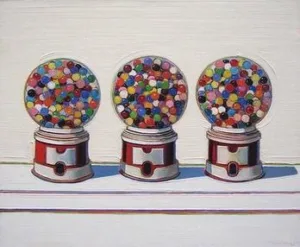

Most painting students are older adults. The ones who stick with it are the ones who are slightly obsessed. They don’t just paint during class; they work tirelessly during the week. Most of my students stick with me over long periods of time, and build an esprit de corps among themselves. Perhaps their peer-to-peer learning and encouragement are as essential to their success as artists as anything I tell them.

It seems that any skill that requires long-term effort and concentration will help the older mind, and drawing and painting certainly qualify. The beautiful-and maddening-thing about painting is that it’s not ever really mastered. I’ve been at it for decades and there’s still always something to learn.

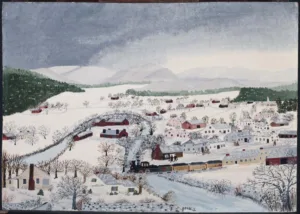

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.