I sometimes have students tell me, “I hate to draw!” What they usually mean is that they’re afraid of drawing. Part of this is because of the lie our culture tells us about drawing, that it’s an innate skill rather than a learned discipline. These students worry that when God was handing out the talent, they were elsewhere. That’s a horrible misunderstanding of how drawing works.

As with language, we all have different fluidity with drawing, but very few of us can’t do it. I once did an experiment where I taught Dr. Amy Vail to draw over her protestations of incompetence. “I thought measuring was cheating,” she told me. If you are not mentally handicapped and you have an interest, you can learn to draw.

Modern art must take part of the blame here

Much 20th and 21st century art has the knack of looking like the artist can’t draw, when the exact opposite is true. Ann Trainor Domingue uses simplified forms of people and boats but don’t be fooled; I’ve sailed with her and she draws beautifully. That simplification is the endpoint of a lifetime of drawing, not its beginning.

Painting is drawing

What drawing-resistant students don’t realize is that painting is just drawing with brushes. It’s easier to understand some of drawing’s principles in graphite than in messy paint. Fixing mistakes is a lot faster with an eraser than a scraper.

Feeling the relationship between the brush and the pencil makes for better, lighter brushwork. They’re two variations of the same basic tool.

Think of drawing as the grammar of art, and color as art’s vocabulary. Just as with language, many of us understand grammar intuitively, but we need education to lift it to its highest level. We all start with some vocabulary, but that expands with reading and study.

That’s not to downplay the mysterious part of the brain that makes language and art possible. It’s just that we all have the basic tools imprinted in us.

In art school, students spend a year on the fundamentals of drawing and color theory before they ever start painting. In a way, this mirrors our natural experience of picking up a pencil or crayon long before we discover the brush.

But I don’t have a lifetime to learn to draw!

I don’t expect you to spend a year drawing an extremely foreshortened skeleton. But understanding measurement, perspective, and shading will make your painting better. I’ve written innumerable posts on drawing-just go over to the box on the right and type in “how to draw” and start reading.

But reading isn’t enough. You must practice. The good thing is, drawing is easy and cheap. I like Strathmore’s Visual Journal and a #2 mechanical pencil. If you want more refinement, my readers and I recommended fancier products here.

Stick two pencils in the ring binder of your sketchbook and toss it in your backpack or purse. Pull it out whenever you have fifteen minutes to kill. The ‘news’ on your phone will remain unchanged whether you spend that time scrolling or drawing, and you’ll have something to show for your time if you draw instead.

Drawing from life is better than drawing from photos (because it’s more difficult) but any drawing is good practice. Just a few minutes a day is all you need.

Drawing is my personal refuge

I may not always make it to my easel, but I can always draw. Even a few moments with my sketchbook clears my mind, gives me ideas, and makes me feel creative again.

I’m watching a close friend struggling with early-onset dementia. She may not remember what she told me last week, but she can still draw beautifully. A habit of sketching and drawing has given her a vocabulary independent of words.

My 2024 workshops:

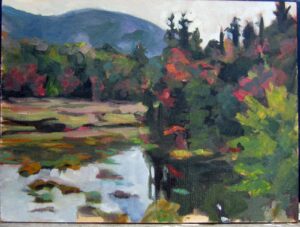

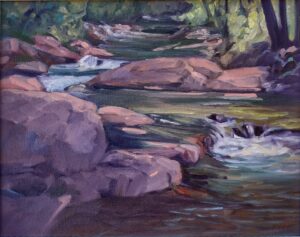

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.