“I'm wondering if you would do or have done a blog post about transitioning from in-the-field studies to larger studio paintings of the same subject. Or is it better to paint larger in the field?” a reader asked.

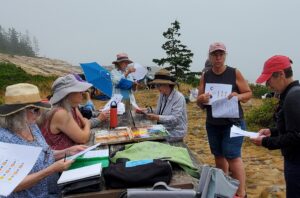

If you have the time and stamina to do a large field painting, they’re a great experience. Everyone should try it to see if they (and their equipment) are up to the challenge. However, there are limitations. You can’t finish a large painting in less than one very long day. The light, the tide, and even the weather will change. You can break the painting into two or three morning or afternoon sessions, but you’ll often be painting in radically-different conditions.

My go-to field easel is an Easy-L pochade box. It can hold a canvas up to 18” high. To go larger, I switch to a Take-It easel, which can hold a very large painting. In high winds, that sometimes needs to be pegged down, or it will go sailing.

In watercolor, I work small on my lap. When I work larger, I use a Mabef swivel-head easel because it can hold a full sheet of paper and it swings absolutely flat in a second.

These are expensive options. If I were testing whether I wanted to work big outdoors, I’d lug my studio easel outside, or borrow a friend’s easel to try.

Henry Isaacs simply throws his work at his feet. “I never use an easel, whether the canvas is 8x8″, or 80x80″. I simply place the canvas on the ground, sand, or grass, and continually walk around it painting from all sides, all at once,” he said.

Even with equipment and stamina questions answered, there are good reasons to start small and work your way up. Small studies are an excellent way of understanding the subject. They capture light and form better than a photograph. They allow you to work on the edge of abstraction, not overworking the material.

When scaling up the painting, it makes sense to grid up from your drawing instead of from a photograph. Make your grid on a bit of plexiglass or clear acrylic instead of on the original painting. I once did a study of boats in watercolor in a notebook and put crop marks over it in Sharpie. Later, I realized it was a bad crop, but it’s unrepairable. You can see that watercolor in this post about the mechanics of scaling up a painting.

The Indigenous and Canadian collection at the National Gallery of Canada has an excellent collection of small Group of Seven field studies. Among these are JEH MacDonald’s study for his iconic The Tangled Garden. The study is small, around 8x10” and done on cardboard mounted on plywood. The finished painting is wall-sized, around 48x60”. MacDonald worked out his design, including the complementary color scheme and graceful arching sunflowers, in his field study. The large painting is remarkably faithful to his original idea.

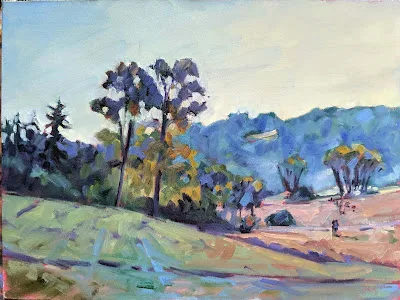

Sometimes it makes sense to add elements to the larger painting to break up the expanses. I’ve included a field study of my own along with its larger painting, at top. The subject was a vineyard along Keuka Lake in New York’s Finger Lakes. I enlarged the tree and added the characteristic rock scree of the Finger Lakes to the foreground. I’m not sure I’d do the same thing today.

Therein lies another lesson: the way we approach painting is constantly evolving, or we become a caricature of ourself. I look at old paintings and often think, “I’d do that differently now.” That doesn’t necessarily mean better; it just means I’ve changed.