I watched eagerly as Cardinal electors arrive for the Papal Conclave in Rome, which starts today. Although I’m not Catholic, the Papal Conclave is a fascinating glimpse into history. The College of Cardinals have been doing this (with periodic irruptions) since 1059 AD. Only four have been held in my adult lifetime.

Much hay has been made recently about the late Pope Francis’ love of Caravaggio, in particular The Calling of St Matthew. Michelangelo, painter of the Sistine Chapel, is the artist most associated with the Vatican, but so also are Raphael, Caravaggio, Bernini, and Leonardo da Vinci.

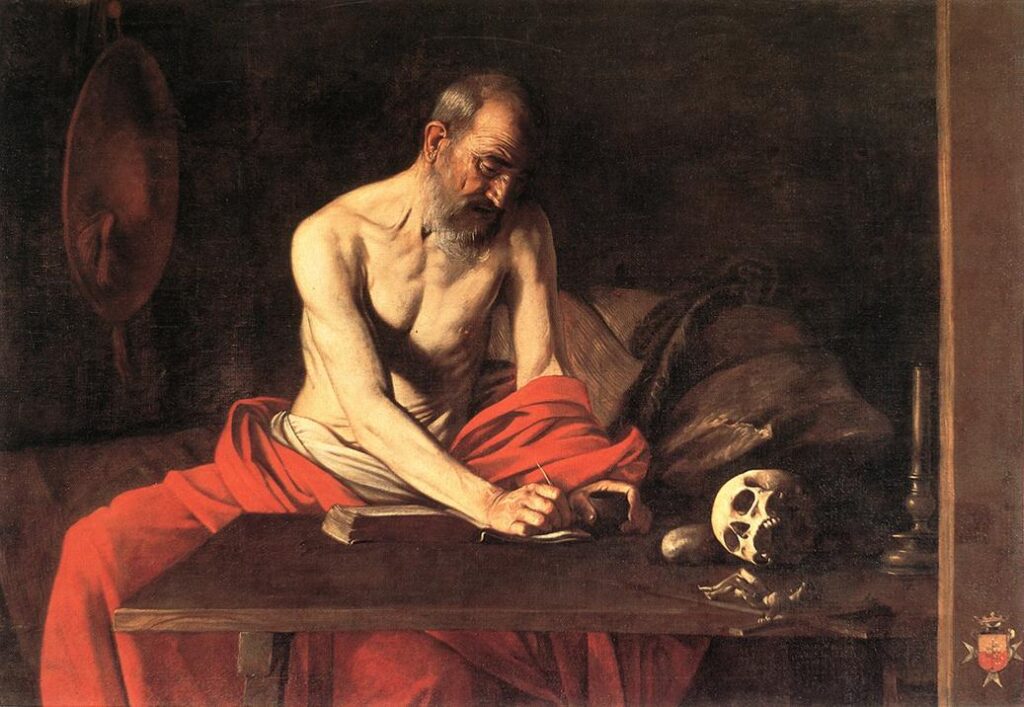

The difference between those others and Caravaggio isn’t his chiaroscuro, as radical as it is. It’s the humanity of his figures. Although his figures are dressed in late 16th century finery, there’s an everyman quality to them that we recognize immediately.

Francis’ love of Caravaggio is ironic, considering the difficulties the artist had with his sometimes patron, Cardinal Scipione Caffarelli-Borghese. Borghese was the nephew of Pope Paul V. When Paul V was elected Pope, Borghese was made a Cardinal, the papal secretary and the effective head of the Vatican government. Of course, he amassed great power and wealth. With that came the capacity to steal vast collections of art.

Included were several Caravaggios. Among them, Borghese appropriated Caravaggio’s Madonna and Child with St. Anne, commissioned in 1605 for a chapel in the Basilica of Saint Peter’s. It was rejected by the College of Cardinals, allegedly because of its earthly realism and unconventional iconography. However, archives show that Borghese rigged the deal from the start so that the altarpiece would end up in his own collection.

Caravaggio was temperamental to start with, but his treatment by Borghese couldn’t have helped. In 1606, he fled to Malta after murdering a gangster in a street brawl. I recently saw two of his paintings there: The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (which is enormous and dark) and Saint Jerome Writing (which is intimate and accessible). These are in St John’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta, which was one of many exuberantly-Baroque churches, basilicas and cathedrals we toured. At the end of my visit, I felt if I spent much more time in all that gilt and paint, I’d be an atheist.

This is of course, unfair. I’m a New England evangelical, which means my church style is austere.

Having said that…

I’ve heard people say that the gold in St. Peter’s should be melted down and the money given to the poor. That’s absurd on the face of it, since every bit of gilt there is in the form of artistic masterpiece, worth many times the nominal value of the metal.

The truth is that without the church, there would be no western art. All artistic expression from the Middle Ages until the Enlightenment hangs from the power and energy of the church. The church created modern western art as we know it, including that which followed the church age.

The Reformation unleashed a wave of iconoclasm across Northern Europe and England in the 16th century. The result was the destruction of more paintings than were ever saved. The church not only commissioned great art, it has preserved it. That was sometimes in the face of danger, as in the case of the Ghent Altarpiece.

Let the games begin

Meanwhile, the Papal Conclave begins its stately procession to elect the 267th recognized pope. Let the intrigue, speculation, false starts, and rumor begin!

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.