It’s not about money, and nobody gets to say whether it’s good or bad. Too bad more art isn’t like NaNoWriMo.

|

|

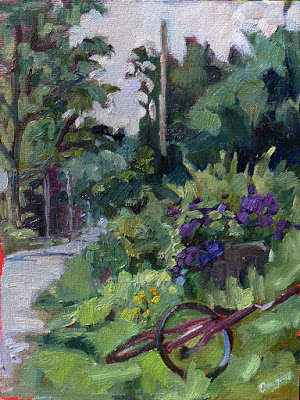

Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid, c. 1670–71, Johannes Vermeer, National Gallery of Ireland

|

November might be our month to express gratitude, but it’s also

NaNoWriMo, or National Novel Writing Month. My third daughter has been participating since she was in high school. Now, her younger brother also spends the month of November writing a novel.

“I might as well do it while I still can,” is their rationale. That reflects a sad view of adulthood in America. Young people see their mid-twenties as the end of all self-actualization, when in truth it ought to be just the beginning.

I’ve mostly interacted with NaNoWriMo as a mom. My kids knew that, “I can’t rake leaves, Mom, I’m short on my word count,” stood a pretty good chance of working.

Occasionally one of my older friends takes a swing at NaNoWriMo. This year it’s a retired religious who’s in palliative care in Jerusalem. She’s the survivor of two different cancers, breast and adult Ewing sarcoma, and she has lots of professional experience writing and editing. It’s been interesting to watch her struggle with the NaNoWriMo challenge.

|

|

Paul Alexis Reading to Émile Zola, 1869–1870, Paul Cézanne, Museo de Arte de Sao Paulo

|

Since 2006, almost 400 NaNoWriMo novels have been picked up and published by publishing houses. These include the best-seller

Water for Elephants by

Sara Gruen. More have been successfully self-published. (A complete list is available

here.) Recently, winners have received five free, paperback proof copies of their manuscripts that they can use for marketing. They’re also encouraged to do revisions in a “Now What?” month, where published authors help them polish up their work for submission.

NaNoWriMo focuses on the doing, not the quality of the results. A winner is a person who completes their 50,000-word work in the one-month window. “If you believe you’re writing a novel, we believe you’re writing a novel too,” says their website.

The participation rate is huge. This year, 441,184 people are participating, from all over the globe. There will be about 40,000 winners. These people will write 1,667 words a day, every day, for thirty days straight. That’s a lot of words. It supports what art teachers often say: inspiration lies in methodical disciplined action, not in some mad flash of genius.

As with so much other crowd-sourcing, NaNoWriMo was only possible after the development of the internet diffused the power of traditional publishing. It’s popular with young people. I expect that their tastes and style, coupled with this engine of quick distribution, will create a period of great achievement in literature.

|

|

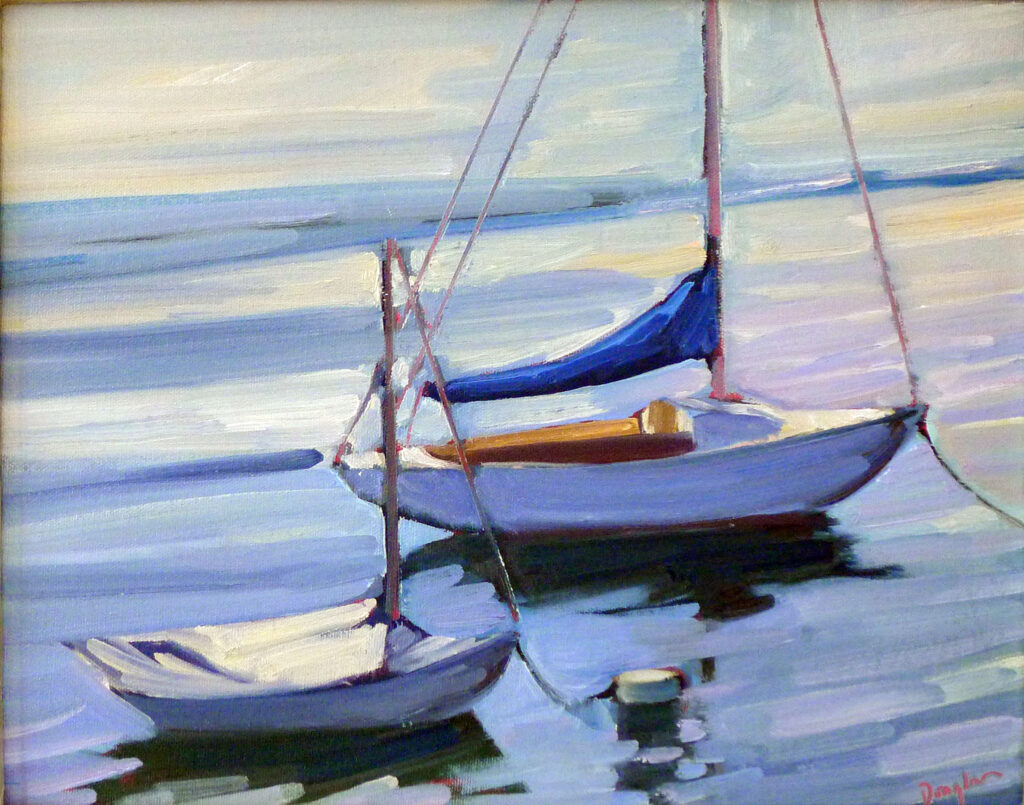

Young Man Writing, 1650-1675, Jacob van Oost, Musée d’arts de Nantes

|

I don’t need to read my son’s story; he’s already told it to me. As he talked, I smiled at his vocabulary and word structure. He’s always been good with language, but I’m sure these forays into forced-march fiction have influenced how he thinks and speaks.

Complete works don’t just fall out of your head onto the paper, whether they’re painted or written. They’re clawed out in great chunks, then endlessly revised. Painting or writing may be intensely satisfying but they’re also hard work.

We humans love to spin stories, and we love to hear them. I love NaNoWriMo because it celebrates that inventive human spirit. I love it because it’s never been mostly about the business of art, but about the simple joy of creativity. I love it because nobody’s appointed themselves the arbiter of what’s good or bad. Too bad more art isn’t like that.