If I had more time, I would have written a shorter essay.

|

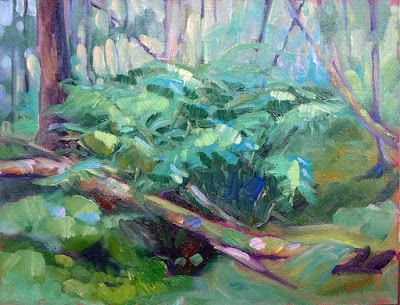

| Coast Guard Inspection, 6X8, oil on canvasboard. |

The above witticism has been attributed to many people because it’s a universal truth. President Woodrow Wilson put it thus: “If it is a ten-minute speech it takes me all of two weeks to prepare it; if it is a half-hour speech it takes me a week; if I can talk as long as I want to it requires no preparation at all. I am ready now.”

On Wednesday, I wrote and designed an ad with exactly 24 words of new copy; it took five hours. Then I made a short promotional video. I spent 12 hours to make two minutes of finished video.

This won’t surprise anyone in the creative fields. Editing is an important skill in any creative endeavor.

|

| Blueberry Barrens, Clary Hill, 24X36, oil on canvas. |

When I started blogging experts recommended that a blog post be kept to a thousand words. Today, I try to keep it around 500-600 words. There are many things that interest me, but if they don’t support the main trunk of the narrative, they’re ruthlessly scrubbed out.

This has changed my writing style, just as ruthless editing has changed my painting style. There are things I used to be able to do with pen or brush that I can no longer do. Losing some skills is the price we pay for pursuing mastery of others.

I’d like to blame simplification on our sleek modern sensibilities, but the quote at the head of this page dates from at least 1657. It was written (more wordily) by the French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal. For centuries, writers have aimed for spare simplicity.

|

| Main Street, Owl’s Head, 16X20, oil on gessoboard. |

There are, of course, actions and reactions in public taste. Following hard on the heels of Pascal’s geometry came the French Rococo, with painters like Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Antoine Watteau and François Boucher creating absurdly exuberant paintings. But rococo had a limited run; within a few decades, tastes swung back to the neoclassical.

There’s a limit, apparently, to the frenzy the human mind can tolerate. At the same time, there are paintings that seem empty to us. Dutch Golden Age church interiors come to mind, as do most of the experiments of 20th century op art. There isn’t enough there to hold our interest. Editing is a delicate balance.

I’ve written before on the question of simplification in painting, most recently here. It’s not a question of taking things out for the sake of simplicity, but of ruthlessly paring away what doesn’t matter. That makes room for what’s important. That’s not necessarily content; it could be rhythm, texture, color or line.

|

| The Late Bus, 8X6, oil on archival canvasboard. |

“When in doubt, take it out” is another pithy aphorism that can also apply to painting. I’ve spent vast amounts of time trying to squeeze an idea into a painting or essay only to realize it was superfluous from the get-go.

In painting, the best time to do these edits is before you pick up a brush. Paper and charcoal (or pencil) are cheap and forgiving. Andrew Wyeth was a careful planner; his preparatory sketches are worth studying. Just as an outline is invaluable for the writer, a sketch is invaluable to the painter.

Paintings almost never benefit from last-minute additions or changes to the composition. These decisions need to be taken early on. Jan van Eyck may have moved feet and hands and added the little dog to the Arnolfini portrait, but he did so in the underpainting. The essential composition was worked out long before he got to the end.