Painters spend lots of time thinking about the subtractive color system. We spend very little time thinking about the additive system. That’s a mistake, because this is the color of light.

|

| A deer I painted years ago as a demonstration for my class. Shadows are the complement of the morning light. |

Every artist is familiar with the three primary colors: red, blue and yellow, and their complements, the secondary colors green, orange and violet. This is the fundamental color wheel for the subtractive color system, or what’s used for paint and ink.

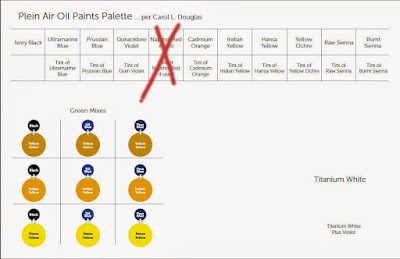

There’s another set that became more important in the 20thcentury, with the rise of electric lights and then electronics. These are the so-called additive color primaries, which are red, green and blue. This color system doesn’t have a color wheel, but it does have complements, which are shown below.

|

| Additive complements (left) and subtractive complements (right). Courtesy Wikipedia. |

Painters spend lots of time thinking about the subtractive color system. We spend very little time thinking about the additive system. That’s a mistake, because this is the color of light.

For painters, color theory is a balance between natural light (additive color) and their paints (subtractive color). That’s mind-blowing but they’re not alone in this challenge. Despite working in an additive-color medium, many web designers still think in terms of subtractive color. This system has influenced our aesthetics since the 18th century, and we don’t let go of what ‘looks right’ easily.

But in practical terms, shadows are the absence of light. If light is full-spectrum, then its shadows will be full-spectrum too. That means a white light will cast a grey shadow.

However, natural light is far more complex than that. It seldom shows up with all wavelengths being equal.

|

| Sunrise, or the so-called ‘golden hour’ on Beech Hill. The shadows are definitely blue. |

For this reason, artists have a useful rule: shadows are the complement of the color of the light. In the north on a snowy morning, golden light casts blue-violet shadows on the snow. In overcast light, the shadows are vaguer and full-spectrum, meaning they appear greyer. That’s easy to see, and demonstrates an idea that you can then generalize to all subjects. Although you should never trust your camera for color, I have included two photographs that show this.

|

| Midday at the same location, the light is diffuse and so are the shadows. |

It’s a mistake to get too attached to theory, however. For one thing, light is tricky. And for another thing, ‘primary color’ is another one of those constructs that we use because it’s useful, not because it’s absolute or provable. Our understanding and technologies are imperfect. CRT televisions of the 20th century were dull compared to modern LED screens. As technology got better, so did the color gamut, and what was considered ‘primary’ changed accordingly.

Most importantly, all these color systems are a dim mirror of the interaction of natural light and the human brain. Both are complex and imperfectly understood.

Light and shadows exist in the additive system, so your understanding of primaries is wrong if it’s based on what you learned in kindergarten. The complement of yellow in subtractive color is violet. The complement of yellow in additive color is blue. So, if the light is golden, the complement is more likely to be blue than violet.

|

| At sunset, shadows appear black. There’s color in those darks, but our eyes can’t process it. |

On the other hand, at sunset, the light is often red. The complement of red in additive color is cyan, but we almost never see any colors in the shadows at sunset. Instead, they’re just black, because we’ve hit the limit of what our poor rods and cones can process.

There’s a lot of latitude in what colors you can make your shadows, as long as you maintain the warm-cool balance. And—as always—all the theory in the world is no substitute for observation.