Two opportunities to learn in mid-coast Maine

|

| Meeting Up, by Ann Trainor Domingue, acrylic on canvas |

Baby Joshua and his mom are doing great, so I can concentrate on work again. There are several things I should have told you about and missed with the excitement of the last two weeks. Here are two very important ones.

I’m bringing

Ann Trainor Domingue to teach a day-long workshop in my studio because she does something that seems magical to me, and I want to know how. Ann paints lyrical, mysterious, narrative paintings, seemingly drawn from within her own psyche. “I love the same things you do about New England. I just reflect on them in a different light,” she says. Annie’s developed a series of exercises to loosen up our thinking, and they will be good for everyone, no matter what their style.

|

| Here’s Annie! |

Uncovering Your Mark, with Ann Trainor Domingue

Sat June 6th, 10-4

Carol L. Douglas Studio

394 Commercial Street, Rockport, ME 04856

Cost $95 per person.

Confused by too many options? Feel uninspired? Need help to get back to your artmaking? Uncovering Your Mark workshop could be just what you need to find your way!

Discover personally meaningful imagery and ideas through a fun guided exploration of things you love. Bring clarity and focus to help make sense as you implement fresh ideas for this phase of your lifelong art journey.

Think quietly about what kinds of things energize you. Sort and combine insights to form something new that feels more authentic by finding your mark.

Take time to work on loose sketches to explore these exciting new ideas and directions to help you stay on your path.

This workshop is a hands-on class aimed at artists of all levels. The first part of the class is a process of guided inquiry. Then, students will apply their self-discoveries through small scale sketching exercises and preliminary color play. It’s strictly limited to twelve students so you’ll get lots of attention. Every style is welcome.

Ann Trainor Domingue is a graduate of Rhode Island College with a BA Studio degree in painting. Her career has included working in advertising, as a teacher and as a painter. She is represented in public collections and galleries nationwide.

|

| Tin-foil hat, by Carol L. Douglas. You don’t have to learn about painting reflections by looking at a vase! |

Next session of weekly classes in my Rockport studio starts next week.

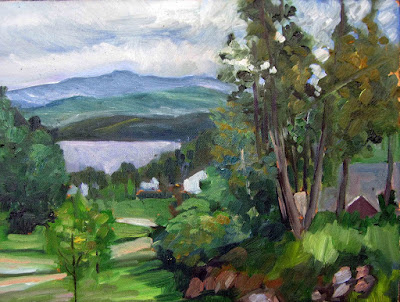

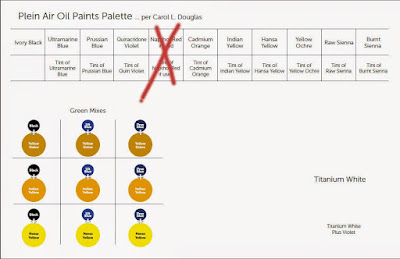

Some people wonder what we paint when the winter weather drives our class indoors. I build still lives, but they aren’t typical. For example, yesterday’s creation was a clash of greens including pine boughs, gift bags, wine bottles and more. The idea was to learn to mix and use a medley of greens without using any green out of a tube. That’s excellent preparation for spring, which really is just around the corner.

Marie told me, “I always come in and see a still life and think, ‘ugh’, but then I get into it and it’s great.” I’m not interested in still-life as a genre either, but I think painting from life is critically important, so I make an effort to make them unusual and interesting.

|

| Back it up (hard drive and bubble wrap), by Carol L. Douglas |

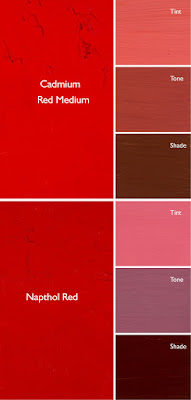

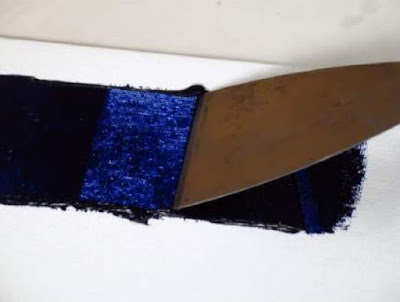

Working in my studio gives us a great opportunity to focus on color theory and technique. We have more time to concentrate on mixing colors and brushwork than we do in the field, where the demands of the scene takes over.

Our next mid-coast Maine painting session will meet on Tuesday mornings, from 10-1. The dates are:

February 25

March 3

March 10 (followed by a two-week break while I hare off to Argentina)

March 31

April 7

April 14

|

| Peppers, by Carol L. Douglas |

Painters are encouraged to broaden their skills in drawing, brushwork and color. Your own individual style will be nurtured. We’ll learn how to paint boldly, with fresh, clean color, to build commanding compositions, and to use hue, value and line to draw the eye through our paintings.

Watercolor, oils, pastels and acrylics are welcome. Because it’s a small group, I can work with painters of all levels. The fee is $200 for the six-week session, and we meet at 394 Commercial Street in Rockport.