Pam’s paints weren’t cheap; they were by reputable manufacturers. But she was caught in the maze of historic names and convenience mixes.

|

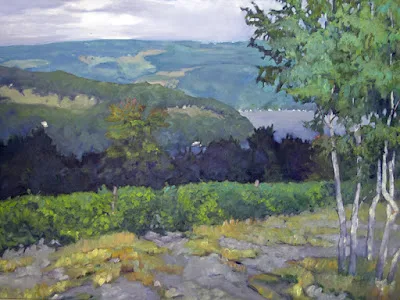

| Spring Allee, 14X18, oil on archival canvasboard, available. |

Last week my students did a green-mixing exercise. Pam Otis had a tough time getting the proper mixes out of the yellows on her palette. After class, she sent me photos of every yellow she had. I spent an instructive half-hour happily looking up each tube.

I know, generally, what’s in colors, but different manufacturers have different ways of getting to that point. If the paint tube isn’t marked (or has been crimped or damaged so you can’t read the tiny type), you must research the paint on the manufacturer’s site. Often, you’ll learn something, because paints are constantly changing.

|

| Vineyard, 30X40, oil on canvas, available. |

Some changes are due to market conditions. PO49, quinacridone gold, was a very useful color (as all the quinacridones are). However, it was discontinued by the auto industry in 2001. The fine arts market for pigments is miniscule, so PO49 disappeared. Most modern quinacridone golds are convenience mixes of quinacridone orange (PO48) and nickel azo yellow (PY150). Both are perfectly fine pigments, but they work differently in mixes than the original pigment.

Other substitutions are more inscrutable. The siennas are ancient pigments made of dirt—a mixture of iron and manganese oxides, to be specific. In its natural state, this pigment is yellow-brown and called raw sienna. Cooked, it turns red and is burnt sienna. Along with ochre and umber, raw sienna was among the first pigments ever used by prehistoric humans. It has been used ever since, because it’s cheap, plentiful, harmless, and doesn’t fade. Modern earth pigments are all manufactured analogues, but are chemically indistinguishable from the old mined ore.

I have no idea why Winsor & Newton substitutes a combination of burnt sienna (PR101) and yellow ochre (PY42) for ordinary raw sienna. But that may be why some yellow ochres and raw siennas are indistinguishable out of the tube.

|

| Bracken fern, 9X12, oil on archival canvasboard, available. |

A hue is a blend of less-expensive pigments. There is nothing inherently wrong with hues, but they don’t behave the same as the pigments they’re named after. “Cadmium yellow hue” may look like cadmium yellow coming out of the tube, but it makes insipid greens.

Then there is the stuff that watercolorists call Gamboge. The real thing came from tapping the latex of the Garcinia, or Gamboge Tree. It’s a beautiful, transparent, non-staining orange-yellow, but it’s also extremely fugitive (as vegetable dyes tend to be). So, manufacturers substitute other pigments and call the result New Gamboge. The most common ingredients are nickel azo yellow and anthrapyrimidine yellow (PY108) However, there are as many formulas as there are manufacturers, and every combination behaves differently.

|

| Spring Greens, 8X10, oil on archival canvasboard, available. |

The origins of Indian yellow have long been disputed. It was said that it was extracted from the urine of cows fed a diet of only mango leaves. 20th century, art historians doubted this, but recent chemical analysis of historic samples confirm the source as animal urine.

We now reject the idea of starving cows to create pretty pigments (although euxanthic acid can be synthesized in the lab). Today we use combinations of nickel azo, hansa yellow, and quinacridone burnt orange. It’s a terrific paint for making dark greens. The trouble, again, is that every manufacturer has its own formula for Indian Yellow.

Pam’s paints weren’t cheap; they were by reputable manufacturers. But she was caught in the maze of historic names and convenience mixes. Knowing how to read the CII code on your paint tube is important.

The CII code consists of two letters and some numbers. Most paints start with a “P” which means it’s a pigment, not a dye. The next letter is the color family: PR is red, PY is yellow, etc. The number is the specific pigment included in the tube.

Save this link somewhere accessible from your phone. You’ll need it when you shop. This pigment guide was built for watercolors but is generally true across all media.