But it’s a jungle out there.

|

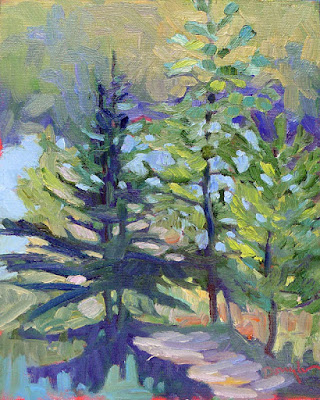

| Apple blossom time, 9X12, oil on canvasboard, available. |

My friend Jonathan Becker took a lovely photo of spring outside his back door in Samaria. There are poppies to the left and something that looks like flax to the right—and beyond that a chain-link fence and the desert.

Overshadowed by the cataclysm in Ukraine, Israel has sustained deadly attacks in recent weeks. They have people talking about another Intifada. My knowledge of Israeli geography is hazy, but I believe that Samaria is part of the West Bank. Jonathan is hardly sitting pretty.

|

| Spring in Samaria, photo courtesy of Jonathan Becker. |

And yet spring blooms, as it has always done so far. “Nature preaches peace,” I said to Jonathan.

“But it’s a jungle out there,” he replied. Well, he’s the one sitting on the tinderbox, not me.

I recently wrote about purpose, that indefinable goal that drives all artists. “I’d be hard-pressed to put my mission statement into words,” I said, and that remains true. But relative to landscape painting—and let’s face it, it’s primarily what I do these days—my conversation with Jonathan hit me like a bullet on the N-train in Sunset Park.

Nature preaches peace.

|

| Blueberry barrens at Clary Hill, watercolor on Yupo, 24X36, available. |

Jonathan may wake up every morning of this Pesach season wondering what fresh hell will be visited on his little community, but the flax and poppies know no such fears. They bloom as they’ve always bloomed.

I’m reading the news these days from under my security blanket, with one eye on my phone, the other screwed firmly shut. I haven’t known such a fraught period in my lifetime. There will be no blossoms in Mariupol, which has sustained scorched-earth bombings. There are reports of chemical weapons being used there, which hasn’t happened in Europe since WW2. The term Mutually Assured Destruction is back in my mind for the first time since 1980. The economic news is worrisome, and I’m sick about the shootings in Brooklyn.

But my Israeli friends? They’ve been living in such uncertainty since 1948, and they’re generally cheerful about it. I could learn a lot from their attitude. “Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof,” says the gospel of Matthew, and it’s a good thing to remember.

Every morning on Beech Hill, the scene changes infinitesimally. Each branch is covered with tiny buds of green or pink, waiting expectantly for warmer air. The blueberry barrens are turning green in stripes, looking like a cockeyed Christmas sweater. Woodpeckers are back, as are the ticks (who aren’t really evil, merely looking for a free lunch).

|

| Sometimes it rains, oil on archival canvasboard, 9X12, available. |

Nature preaches peace.

Yes, I’m aware that under the verdancy of spring, hawks are still killing voles and fishers are stalking porcupines. Nature is red in tooth and claw. But nature doesn’t seek the wholesale extirpation of its enemies, as some of mankind seems to be doing right now.

Nature continues in its preordained courses. The Northern Hemisphere awakens from winter, its seasonal death forgotten. Life is gradually restored.

We landscape painters, in copying nature, can preach peace secondhand. That’s a mission I can wholeheartedly embrace.